고정 헤더 영역

상세 컨텐츠

본문

C H A P T E R 4

Explaining Institutional Performance

IT IS BEST to begin a journey of exploration with a map. Figure 4.1 shows the level of institutional performance of each of Italy's twenty regions. The most striking feature of this map is the strong North-South gradient. Although the correlation between latitude and institutional performance is not perfect, the northern regional governments as a group have been more successful than their southern counterparts. To be sure, this discovery is not unexpected. In the words of a thousand travelogues, "the South is different."

We shall have occasion to return to this conspicuous contrast between North and South in Chapters 5 and 6. However, if our purpose is not simply description, but understanding, this observation merely reformulates our problem. What is it that differentiates the successful regions in the North from the unsuccessful ones in the South, and the more from the less successful within each section? As adumbrated in Chapter 1, we shall concentrate here on two broad possibilities:

• Socioeconomic modernity, that is, the results of the industrial revolution.

• "Civic community," that is, patterns of civic involvement and social soli darity .

Toward the end of this chapter we shall also explore briefly several other plausible explanations, which turn out to be less powerful.

SOCIOECONOMIC MODERNITY

The most important social and economic development in Western society in the last several centuries has been the industrial revolution and its aftermath, that colossal watershed in human history that has fascinated social theorists, Marxists and non-Marxists alike, for more than one hundred years. Vast populations moved from the land to the factory. Standards of living increased almost beyond belief. Class structures were transformed. Capital stocks, both physical and human, deepened. Levels of education and standards of public health rose. Economic and technological capabilities multiplied.

Political sociologists have long argued that the prospects for stable democratic government depend on this social and economic transformation. Empirically speaking, few generalizations are more firmly established than that effective democracy is correlated with socioeconomic modernization.1 Reviewing the incidence of successful democracies around the world, for example, Kenneth Bollen and Robert Jackman report that "the level of economic development has a pronounced effect on political democracy, even when noneconomic factors are considered. . . . GNP is the dominant explanatory variable."2 Wealth eases burdens, both public and private, and facilitates social accommodation. Education expands the number of trained professionals, as well as the sophistication of the citizenry. Economic growth expands the middle class, long thought to be the bulwark of stable, effective democracy. After examining the successes and failures of urban governments around the world, Robert C. Fried and Francine Rabinovitz concluded that "of all the theories to explain the performance differences, the most powerful one is modernization."3

In Italy much of this transformation has occurred within the last generation, although it had begun at the end of the last century. Change has touched all parts of the peninsula but, as our trip from postindustrial Seveso to preindustrial Pietrapertosa reminded us, the North is much more advanced than the South. It is hard to believe that this stark contrast in levels of affluence and economic modernity is not an important part of the explanation—perhaps even the sole explanation—for the differences we have discovered in the performance of regional governments.

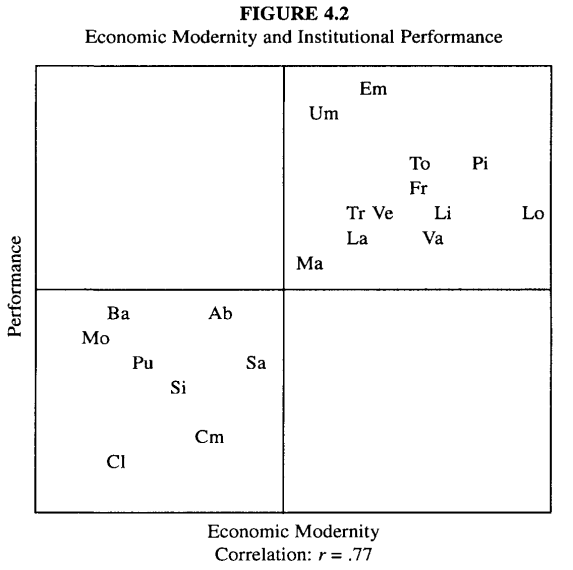

Figure 4.2, which arrays the Italian regions according to their degree of economic modernity and institutional performance, illustrates both the power and the limitations of this interpretation of our puzzle.4

The wealthier, more modern regions of the North (concentrated in the upper right quadrant of Figure 4.2) have a head start over their poorer counterparts in material and human resources. Their advantage is symbolized by the headquarters of the respective regional governments. Contrast the nondescript structures on dusty piazzas in several southern regions with the thirty-story skyscraper in the heart of Milan housing the Lombardia government, built originally for the Pirelli multinational corporation. Public health officers or public works managers in northern regions can call on the full resources of one of the most advanced economies in the world. Their southern counterparts face the daunting problems of underdevelopment with little local help. Take a single but revealing example: in the 1970s there were hundreds of data-processing firms in Milan, but scarcely any in Potenza. Regional administrators seeking help in measuring their problems or managing their personnel are clearly better off in Lombardia than in Basilicata.5

To be sure, it cannot be merely the financial resources available to the regional governments that account for the North-South disparity in performance. Funding for the regional governments is provided by the central authorities according to a redistributive formula that favors poorer regions. Indeed, our survey of institutional performance showed that many of the most backward regions have more funds available than they have been able to expend. Figure 4.2, however, suggests that this fiscal redistribution apparently cannot compensate for the immense differences in socioeconomic and technological infrastructure.

Yet the more closely one examines the patterns in Figure 4.2, the more evident are the limitations of this interpretation. The regions appear divided into two quadrants, the haves and the have-nots, with governments in the latter regions displaying consistently lower levels of performance. The marked differences in performance within each quadrant, however, are wholly inexplicable in terms of economic development.6 Campania, the region around Naples, is more advanced economically than Molise and Basilicata, at the very bottom of the developmental hierarchy, but the two latter governments are visibly more effective than Campania's. Lombardia, Piemonte, and Liguria—the three corners of the famed industrial triangle of the North—are all wealthier than Emilia-Romagna and Umbria (or at least they were in the early 1970s), but the latter two governments were distinctly more successful. Wealth and economic development cannot be the entire story.

Economic modernity is somehow associated with high-performance public institutions—that much is clear. What our simple analysis so far cannot reveal is whether modernity is a cause of performance (perhaps one among several), whether performance is perhaps in some way a cause of modernity, whether both are influenced by a third factor (so that the association between the two is in some sense spurious), or whether the link between modernity and performance is even more complex. We shall return to those more complicated—and more interesting—questions later in this chapter and in the following two chapters.

THE CIVIC COMMUNITY: SOME THEORETICAL SPECULATIONS

In sixteenth-century Florence, reflecting on the unstable history of republican institutions in ancient times as well as in Renaissance Italy, Nicolo Machiavelli and several of his contemporaries concluded that whether free institutions succeeded or failed depended on the character of the citizens, or their "civic virtue.''7 According to a long-standing interpretation of Anglo-American political thought, this "republican" school of civic humanists was subsequently vanquished by Hobbes, Locke, and their liberal successors. Whereas the republicans had emphasized community and the obligations of citizenship, liberals stressed individualism and individual rights.8 Far from presupposing a virtuous, public-spirited citizenry, it was said, the U.S. Constitution, with its checks and balances, was designed by Madison and his liberal colleagues precisely to make democracy safe for the unvirtuous. As a guide to understanding modern democracy, civic republicans were passé.

In recent years, however, a revisionist wave has swept across AngloAmerican political philosophy. "The most dramatic revision [of the history of political thought] of the last 25 years or so," reports a notuncritical Don Herzog, is "the discovery—and celebration—of civic humanism."9 The revisionists argue that an important republican or communitarian tradition descended from the Greeks and Machiavelli through seventeenth-century England to the American Founders.10 Far from exalting individualism, the new republicans recall John Winthrop's eloquent, communitarian admonition to the citizens of his "city set upon a hill": "We must delight in each other, make others' conditions our own, rejoyce together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our community as members of the same body."11

The new republican theorists have not gone unchallenged. The defenders of classical liberal individualism argue that the notion of community lauded by the new republicans is a "dangerous and anachronistic ideal."12 Remarkably, this wide-ranging philosophical debate has so far taken place almost entirely without reference to systematic empirical research, whether within the Anglo-American world or elsewhere. Nevertheless, it contains the seeds for a theory of effective democratic governance: "As the proportion of nonvirtuous citizens increases significantly, the ability of liberal societies to function successfully will progressively diminish."13 We want to explore empirically whether the success of a democratic government depends on the degree to which its surroundings approximate the ideal of a "civic community."14

But what might this "civic community" mean in practical terms? Reflecting upon the work of republican theorists, we can begin by sorting out some of the central themes in the philosophical debate.

Civic Engagement

Citizenship in a civic community is marked, first of all, by active participation in public affairs. "Interest in public issues and devotion to public causes are the key signs of civic virtue," suggests Michael Walzer.15 To be sure, not all political activity deserves the label "virtuous" or contributes to the commonweal. "A steady recognition and pursuit of the public good at the expense of all purely individual and private ends" seems close to the core meaning of civic virtue.16

The dichotomy between self-interest and altruism can easily be overdrawn, for no mortal, and no successful society, can renounce the powerful motivation of self-interest. Citizens in the civic community are not required to be altruists. In the civic community, however, citizens pursue what Tocqueville termed "self-interest properly understood," that is, selfinterest defined in the context of broader public needs, self-interest that is "enlightened" rather than "myopic," self-interest that is alive to the interests of others.17

The absence of civic virtue is exemplified in the "amoral familism" that Edward Banfield reported as the dominant ethos in Montegrano, a small town not far from our Pietrapertosa: "Maximize the material, short-run advantage of the nuclear family; assume that all others will do likewise."18 Participation in a civic community is more public-spirited than that, more oriented to shared benefits. Citizens in a civic community, though not selfless saints, regard the public domain as more than a battleground for pursuing personal interest.

Political Equality

Citizenship in the civic community entails equal rights and obligations for all. Such a community is bound together by horizontal relations of reciprocity and cooperation, not by vertical relations of authority and dependency. Citizens interact as equals, not as patrons and clients nor as governors and petitioners. To be sure, not all classical republican theorists were democrats. Nor can a contemporary civic community forgo the advantages of a division of labor and the need for political leadership. Leaders in such a community, however, must be, and must conceive themselves to be, responsible to their fellow citizens. Both absolute power and the absence of power can be corrupting, for both instill a sense of irresponsibility.19 The more that politics approximates the ideal of political equality among citizens following norms of reciprocity and engaged in selfgovernment, the more civic that community may be said to be.

Solidarity, Trust, and Tolerance

Citizens in a civic community, on most accounts, are more than merely active, public-spirited, and equal. Virtuous citizens are helpful, respectful, and trustful toward one another, even when they differ on matters of substance. The civic community is not likely to be blandly conflictfree, for its citizens have strong views on public issues, but they are tolerant of their opponents. 'This is probably as close as we can come to that 'friendship' which Aristotle thought should characterize relations among members of the same political community," argues Michael Walzer.20 As Gianfranco Poggi has noted of Tocqueville 's theory of democratic governance, "Interpersonal trust is probably the moral orientation that most needs to be diffused among the people if republican society is to be maintained."21

Even seemingly "self-interested" transactions take on a different character when they are embedded in social networks that foster mutual trust, as we shall see in more detail in Chapter 6. Fabrics of trust enable the civic community more easily to surmount what economists call "opportunism," in which shared interests are unrealized because each individual, acting in wary isolation, has an incentive to defect from collective action.22 A review of community development in Latin America highlights the social importance of grass-roots cooperative enterprises and of episodes of political mobilization—even if they are unsuccessful in immediate, instrumental terms—precisely because of their indirect effects of "dispelling isolation and mutual distrust."23

Associations: Social Structures of Cooperation

The norms and values of the civic community are embodied in, and reinforced by, distinctive social structures and practices. The most relevant social theorist here remains Alexis de Tocqueville. Reflecting on the social conditions that sustained "Democracy in America," Tocqueville attributed great importance to the Americans' propensity to form civil and political organizations:

Americans of all ages, all stations in life, and all types of disposition are forever forming associations. There are not only commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but others of a thousand different types— religious, moral, serious, futile, very general and very limited, immensely large and very minute. . . . Thus the most democratic country in the world now is that in which men have in our time carried to the highest perfection the art of pursuing in common the objects of common desires and have applied this new technique to the greatest number of purposes.24

Civil associations contribute to the effectiveness and stability of democratic government, it is argued, both because of their "internal" effects on individual members and because of their "external" effects on the wider polity.

Internally, associations instill in their members habits of cooperation, solidarity, and public-spiritedness. Tocqueville observed that "feelings and ideas are renewed, the heart enlarged, and the understanding developed only by the reciprocal action of men one upon another."25 This suggestion is supported by evidence from the Civic Culture surveys of citizens in five countries, including Italy, showing that members of associations displayed more political sophistication, social trust, political participation, and "subjective civic competence."26 Participation in civic organizations inculcates skills of cooperation as well as a sense of shared responsibility for collective endeavors. Moreover, when individuals belong to "cross-cutting" groups with diverse goals and members, their attitudes will tend to moderate as a result of group interaction and crosspressures.27 These effects, it is worth noting, do not require that the manifest purpose of the association be political. Taking part in a choral society or a bird-watching club can teach self-discipline and an appreciation for the joys of successful collaboration.28

Externally, what twentieth-century political scientists have called "interest articulation" and "interest aggregation" are enhanced by a dense network of secondary associations. In Tocqueville's words:

When some view is represented by an association, it must take clearer and more precise shape. It counts its supporters and involves them in its cause; these supporters get to know one another, and numbers increase zeal. An association unites the energies of divergent minds and vigorously directs them toward a clearly indicated goal.29

According to this thesis, a dense network of secondary associations both embodies and contributes to effective social collaboration. Thus, contrary to the fear of faction expressed by thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in a civic community associations of like-minded equals contribute to effective democratic governance.30

More recently, an independent line of research has reinforced the view that associationism is a necessary precondition for effective self-government. Summarizing scores of case studies of Third World development, Milton Esman and Norman Uphoff conclude that local associations are a crucial ingredient in successful strategies of rural development:

A vigorous network of membership organizations is essential to any serious effort to overcome mass poverty under the conditions that are likely to prevail in most developing countries for the predictable future. . . . While other components—infrastructure investments, supportive public policies, appropriate technologies, and bureaucratic and market institutions—are necessary, we cannot visualize any strategy of rural development combining growth in productivity with broad distribution of benefits in which participatory local organizations are not prominent.31

Unhappily from the point of view of social engineering, Esman and Uphoff find that local organizations "implanted" from the outside have a high failure rate. The most successful local organizations represent indigenous, participatory initiatives in relatively cohesive local communities.32

Although Esman and Uphoff do not say so explicitly, their conclusions are quite consistent with Banfield's interpretation of life in Montegrano, "the extreme poverty and backwardness of which is to be explained largely (but not entirely) by the inability of the villagers to act together for their common good or, indeed, for any end transcending the immediate material interest of the nuclear family."33 Banfield's critics have disagreed with his attribution of this behavior to an "ethos," but they have not dissented from his description of the absence of collaboration in Montegrano, the striking lack of "deliberate concerted action" to improve community conditions.34

Both defenders and critics of civic republicanism have made intriguing philosophical points. We wish to confront the question that has so far remained unaddressed in any empirical way: Is there any connection between the "civic-ness" of a community and the quality of its governance?

THE CIVIC COMMUNITY: TESTING THE THEORY

Lacking detailed ethnographic accounts of hundreds of communities throughout the regions of Italy, how can we assess the degree to which social and political life in each of those regions approximates the ideal of a civic community? What systematic evidence is there on patterns of social solidarity and civic participation? We shall here present evidence on four indicators of the "civic-ness" of regional life—two that correspond directly to Tocqueville's broad conception of what we have termed the civic community, and two that refer more immediately to political behavior.

One key indicator of civic sociability must be the vibrancy of associational life. Fortunately, a census of all associations in Italy, local as well as national, enables us to specify precisely the number of amateur soccer clubs, choral societies, hiking clubs, bird-watching groups, literary circles, hunters' associations, Lions Clubs, and the like in each community and region of Italy.35 The primary spheres of activity of these recreational and cultural associations are shown in Table 4.1.

Leaving aside labor unions for the moment, sports clubs are by far the most common sort of secondary association among Italians, but other types of cultural and leisure activities are also prominent. Standardized for population differences, these data show that in the efflorescence of their associational life, some regions of Italy rival Tocqueville's America of congenital "joiners," whereas the inhabitants of other regions are accurately typified by the isolated and suspicious "amoral familists" of Banfield's Montegrano. In Italy's twenty regions, the density of sports clubs ranges from one club for every 377 residents in Valle d'Aosta and 549 in Trentino-Alto Adige to one club for every 1847 residents in Puglia. The figures for associations other than sports clubs range from 1050 inhabitants per group in Trentino-Alto Adige and 2117 in Liguria to 13,100 inhabitants per group in Sardinia. These are our first clues as to which regions most closely approximate the ideal of the civic community.36

Tocqueville also stressed the connection in modern society between civic vitality, associations, and local newspapers:

When no firm and lasting ties any longer unite men, it is impossible to obtain the cooperation of any great number of them unless you can persuade every man whose help is required that he serves his private interests by voluntarily uniting his efforts to those of all the others. That cannot be done habitually and conveniently without the help of a newspaper. Only a newspaper can put the same thought at the same time before a thousand readers. . . . So hardly any democratic association can carry on without a newspaper.37

In the contemporary world, other mass media also serve the function of town crier, but particularly in today's Italy, newspapers remain the medium with the broadest coverage of community affairs. Newspaper readers are better informed than nonreaders and thus better equipped to participate in civic deliberations. Similarly, newspaper readership is a mark of citizen interest in community affairs.

The incidence of newspaper readership varies widely across the Italian regions.38 In 1975, the fraction of households in which at least one member read a daily newspaper ranged from 80 percent in Liguria to 35 percent in Molise. This, then, is the second element in our assessment of the degree to which political and social life in Italy's regions approximates a civic community.

One standard measure of political participation is electoral turnout. Turnout in Italian general elections, however, is marred as a measure of civic involvement for several reasons:

• Until recently Italian law required all citizens to vote in general elections, and although enforcement of this law was uneven, it presumably brought many people to the polls whose motivation was scarcely "civic."

• Party organizations have an obvious incentive to influence elections, and thus electoral turnout presumably varies with party organizational strength and activity, independently of the voters' own civic engagement.

• In many parts of the peninsula where patron-client networks are rampant, voting in general elections represents a straightforward quid pro quo for immediate, personal patronage benefits, hardly a mark of "civic" involvement.

Since 1974, however, a previously unused constitutional provision for national referenda has been repeatedly employed to resolve a wide range of controversial issues. Some of these deliberations, like the 1974 vote on the legalization of divorce, aroused deeply held religious beliefs. Others, like the 1985 referendum on escalator clauses in national wage contracts, affected the pocketbooks of many voters and engaged class cleavages. Still others, like the 1981 vote on anti-terrorism laws or the 1987 vote on nuclear power, triggered cross-cutting, "new politics" alignments. Each referendum invited citizens to express their views on a major issue of public policy.

Turnout in these referenda has been significantly lower than in general elections, no doubt because of the absence of the "uncivic" motivations enumerated above. Electoral turnout in recent decades has averaged above 90 percent, whereas turnout in successive referenda has dropped steadily from 86 percent in the first referendum in 1974 to 64 percent in the latest referendum in 1987. As Italy's leading student of referenda turnout has observed, "Those who use the vote as an occasion for 'exchange' have scant motivation to go to the polls when the election (as in the case of the referendum) does not offer the possibility of obtaining immediate, personal benefits."39 The primary motivation of the referendum voter is concern for public issues, perhaps enhanced by a keener than average sense of civic duty, so that turnout for referenda offers a relatively "clean" measure of civic involvement.

Regional differences in turnout in the successive referenda have been strong and stable, even as the nationwide averages have diminished. Turnout in five key referenda between 1974 and 1987 for which regionby-region returns are available averaged 89 percent in Emilia-Romagna, as contrasted with 60 percent in Calabria. Moreover, the regional ranking with respect to turnout has been virtually identical across the whole range of issues: divorce (1974), public financing of parties (1978), terrorism and public security (1981), wage escalator clauses (1985), and nuclear power (1987). In short, citizens in some parts of Italy choose to be actively involved in public deliberations on a wide spectrum of public issues, whereas their counterparts elsewhere remain disengaged. As our third indicator of civic involvement, therefore, we have constructed a summary indicator of turnout in five of these referenda (see Table 4.2).40

Although turnout itself in general elections is not a good measure of citizen motivation, one special feature of the Italian ballot does provide important information on regional political practices. All voters in national elections must choose a single party list, and legislative seats are allocated to parties by proportional representation. In addition, however, voters can, if they wish, indicate a preference for a particular candidate from the party list they have chosen. Nationally speaking, only a minority of voters exercise this "preference vote," but in areas where party labels are largely a cover for patron-client networks, these preference votes are eagerly solicited by contending factions. In such areas, the preference vote becomes essential to the patron-client exchange relationship.

The incidence of preference voting has long been acknowledged by students of Italian politics as a reliable indicator of personalism, factionalism, and patron-client politics, and we shall shortly present additional confirmation of this interpretation.41 In that sense, preference voting can be taken as an indicator for the absence of a civic community. Regional differences in the use of the preference vote have been highly stable for decades, ranging from 17 percent in Emilia-Romagna and Lombardia to 50 percent in Campania and Calabria. Table 4.3 summarizes a composite index of preference voting in six national elections from 1953 to 1979, which serves as the fourth element in our evaluation of the "civic-ness" of the Italian regions.42

If our analysis of the motivations and political realities that underlie referenda turnout and preference voting is correct, then the two should be negatively correlated—one reflecting the politics of issues; the other, the politics of patronage. Figure 4.3 shows that this is so. Citizens in some regions turn out in large numbers to declare their views on a wide range of public questions, but forgo the use of personalized preference votes in general elections. Elsewhere, citizens are enmeshed in patron-client networks. They typically pass up the chance to express an opinion on public issues, since for them the ballot is essentially a token of exchange in an immediate, highly personalized relationship of dependency.

Both groups are, in some sense, "participating in politics." It is not so much the quantity of participation as the quality that differs between them. The character of participation varies because the nature of politics is quite different in the two areas. Political behavior in some regions presumes that politics is about collective deliberation on public issues. By contrast, politics elsewhere is organized hierarchically and focused more narrowly on personal advantage. Why these regional differences exist, and what consequences they have for regional governance, are questions to which we shall shortly turn.

As our image of the civic community presumes, our four indicators are in fact highly correlated, in the sense that regions with high turnout for referenda and low use of the personal preference ballot are virtually the same regions with a closely woven fabric of civic associations and a high incidence of newspaper readership. Consequently, we can conveniently combine the four into a single Civic Community Index, as summarized in Table 4.4. Any single indicator of "civic-ness" might be misleading, of course, but this composite index reflects an important and coherent syndrome.

Figure 4.4, in turn, charts the levels of "civic-ness" of each of Italy's twenty regions. In the most civic regions, such as Emilia-Romagna, citizens are actively involved in all sorts of local associations—literary guilds, local bands, hunting clubs, cooperatives and so on. They follow civic affairs avidly in the local press, and they engage in politics out of programmatic conviction. By contrast, in the least civic regions, such as Calabria, voters are brought to the polls not by issues, but by hierarchical patron-client networks. An absence of civic associations and a paucity of local media in these latter regions mean that citizens there are rarely drawn into community affairs.

Public life is very different in these two sorts of communities. When two citizens meet on the street in a civic region, both of them are likely to have seen a newspaper at home that day; when two people in a less civic region meet, probably neither of them has. More than half of the citizens in the civic regions have never cast a preference ballot in their lives; more than half of the voters in the less civic regions say they always have.43 Membership in sports clubs, cultural and recreational groups, community and social action organizations, educational and youth groups, and so on is roughly twice as common in the most civic regions as in the least civic regions.44

Even a casual comparison of Figure 4.4 with Figure 4.1 indicates a remarkable concordance between the performance of a regional government and the degree to which social and political life in that region approximates the ideal of a civic community. The strength of this relationship appears with stark clarity in Figure 4.5. Not only does "civic-ness" distinguish the high performance regions in the upper right-hand quadrant from the laggards in the lower left-hand quadrant, but even the more subtle differences in performance within each quadrant are closely tied to our measure of community life.45 In this respect, the predictive power of the civic community is greater than the power of economic development, as summarized in Figure 4.2. The more civic a region, the more effective its government.

So strong is this relationship that when we take the "civic-ness" of a region into account, the relationship we previously observed between economic development and institutional performance entirely vanishes.46

In other words, economically advanced regions appear to have more successful regional governments merely because they happen to be more civic. To be sure, the link between the civic community and economic development is itself interesting and important, and we shall pay close attention to that link in Chapters 5 and 6. For the moment, it is enough to recognize that the performance of a regional government is somehow very closely related to the civic character of social and political life within the region. Regions with many civic associations, many newspaper readers, many issue-oriented voters, and few patron-client networks seem to nourish more effective governments. What's so special about these communities?

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL LIFE IN THE CIVIC COMMUNITY

Life in a civic community is in many respects fundamentally distinctive. We can deepen our understanding of the social and political implications of "civic-ness" by drawing on our surveys of regional politicians, community leaders, and the mass public.

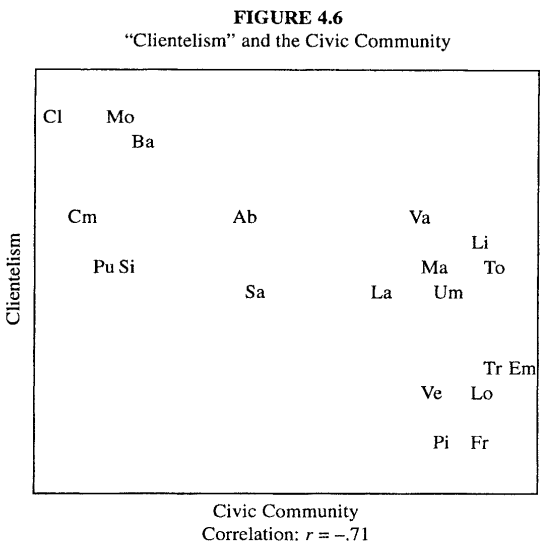

Consider first some independent evidence in support of our assertion that political involvement in less civic regions is impelled and constrained by personalistic, patron-client networks, rather than by programmatic commitments on public issues. Our 1982 nationwide sample of community leaders was asked whether they would describe political life in their respective regions as relatively "programmatic" or relatively "clientelistic." The fraction of respondents describing politics in their region as clientelistic ranged from 85 percent in Molise to 14 percent in FriuliVenezia Giulia. Figure 4.6 shows that these self-descriptions of regional politics are very closely correlated with our Civic Community Index (particularly if one bears in mind the statistical attenuation produced by very small samples and consequent sampling error). Regions where citizens use personal preference votes, but do not vote in referenda, do not join civic associations, and do not read newspapers are the same regions whose leaders describe their regional politics as clientelistic, rather than programmatic.

Evidence from both citizens and politicians helps us trace the incidence of personalized patronage politics. Citizens in the less civic regions report much more frequent personal contact with their representatives than in the civic north.47 Moreover, these contacts involve primarily personal matters, rather than broader public issues. In our 1988 survey, 20 percent of voters in the least civic regions acknowledged that they occasionally "seek personal help about licenses, jobs, and so on from a politician," as contrasted with only 5 percent of the voters in the most civic regions. This "particularized contacting" is not predicted by the demographic character-istics normally associated with political participation, such as education, social class, income, political interest, partisanship, or age, but it is much more common in all social categories in less civic regions. This form of participation seems to depend less on who you are than on where you are.48

Evidence from our surveys of regional councilors is wholly consistent with this picture. We asked each councilor how many citizens had approached him in the previous week and for what reasons. The results from all four waves of interviews were virtually identical. Councilors in Emilia-Romagna, the most civic of regions, reported seeing fewer than twenty constituents in an average week, as compared with fifty-five to sixty contacts per week for councilors in the least civic regions. (Figure 4.7 shows the results for all six regions.)

In the less civic regions, these encounters overwhelmingly involve requests for jobs and patronage, whereas Emilians are more likely to be contacted about policy or legislation. The average councilor in Puglia or Basilicata gets roughly eight to ten requests every day for jobs and other favors, compared to about one such request a day in Emilia-Romagna. On the other hand, the Emilian councilor also reports about one citizen inquiry a day on some public issue, the sort of topic virtually never raised with a councilor in Puglia or Basilicata. In short, citizens in civic regions contact their representatives much less often, and when they do, they are more likely to talk about policy than patronage.

Our exploration of the distinctive features of civic and less civic communities so far has concentrated on the behavior of ordinary citizens, but there are also revealing differences in the character of political elites in the two types of region. Politics in less civic regions, as we have seen, is marked by vertical relations of authority and dependency, as embodied in patron-client networks. Politics in those regions is, in a fundamental sense, more elitist. Authority relations in the political sphere closely mirror authority relations in the wider social setting.49

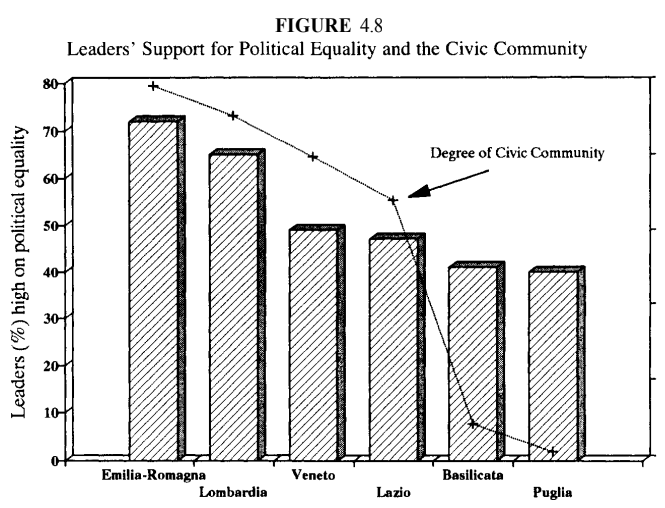

It is not surprising, therefore, to discover that political leaders in the less civic regions are drawn from a narrower slice of the social hierarchy. Educational levels among ordinary citizens in the less civic South are faintly lower than in the North; in 1971 only 2.6 percent of southern residents were university graduates, as contrasted to 2.9 percent of northern residents. Among regional political elites, however, educational levels are significantly higher in the South. All but 13 percent of the councilors in Puglia and Basilicata have a university education, as compared to 3340 percent in the northern, more civic regions. In other words, the regional elite in the less civic regions is drawn almost entirely from the most privileged portion of the population, whereas a significant number of political leaders in the more civic regions come from more modest backgrounds.50 Political leaders in the civic regions are more enthusiastic supporters of political equality than their counterparts in less civic regions. From our first encounters with the newly elected regional councilors in 1970, those in the more civic regions, such as Emilia-Romagna and Lombardia, have been consistently more sympathetic to the idea of popular participation in regional affairs, whereas the leaders in the less civic regions have been more skeptical.51

In those early years, political leaders in the more civic regions lauded the regional reform as an opportunity to enlarge grass-roots democracy in Italy, but leaders in the less civic regions were perplexed by this populist, "power to the people" rhetoric. As the new institution matured during the 1970s and the initial euphoria faded, regional leaders throughout Italy who had once expressed aspirations for direct democracy became more circumspect. Efforts to encourage greater popular involvement in the regional government waned, and attention everywhere shifted instead to administrative efficiency and effectiveness. Nevertheless, clear differences in sympathy for political equality persisted among the leaders of different regions.

Some of these differences in outlook are captured by four "agree-disagree" items that we posed to regional councilors in each of our four surveys from 1970 to 1988, which we have combined into a single Index of Support for Political Equality. Councilors who score high on this Index are avowed egalitarians. Conversely, low scorers on the Index of Support for Political Equality express skepticism about the wisdom of the ordinary citizen and sometimes even have doubts about universal suffrage. They stress the desirability of strong leadership, especially from traditional elites.

Index of Support for Political Equality

1. People should be permitted to vote even if they cannot do so intelligently.

2. * Few people really know what is in their best interests in the long run.

3. * Certain people are better qualified to lead this country because of their traditions and family background.

4. * It will always be necessary to have a few strong, able individuals who know how to take charge.

* Scoring on these items is reversed.

Figure 4.8 shows the sharp differences in support for political equality across the six regional elites, mirroring almost perfectly the "civic-ness" of the regional community. Where associationism flourishes, where citizens attend to community affairs and vote for issues, not patrons, there too we find leaders who believe in democracy, not social and political hierarchy.

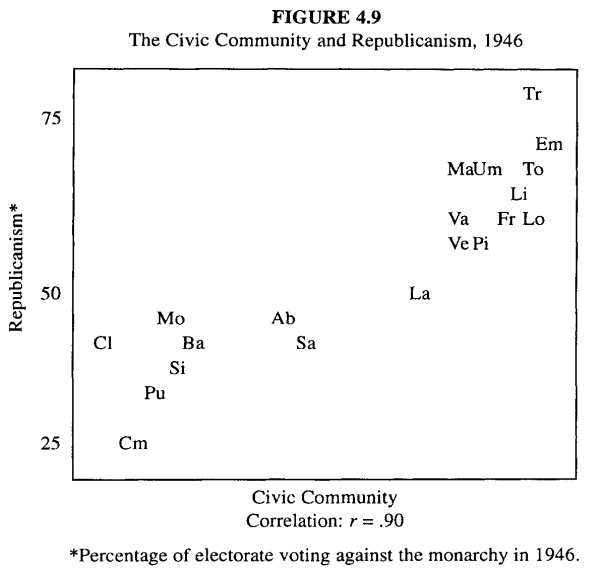

These regional differences in authority patterns have had a powerful and enduring impact on popular attitudes toward the very structure of Italian government. Two striking illustrations of this fact, nearly half a century apart, are provided by the 1946 balloting on whether to retain the Italian monarchy and a 1991 referendum on electoral reform, a far-reaching package of proposals designed to inhibit "vote-buying" and other forms of patron-clientelism. As shown in Figures 4.9 and 4.10, the more civic the social and political life of a region in the 1970s, the more likely it was to have voted for the republic and against the monarchy thirty years earlier, and the more likely it was to support egalitarian electoral reform more than a decade later. Citizens in the more civic regions, like their leaders, have a pervasive distaste for hierarchical authority patterns.

In short, civics is about equality as well as engagement. It is impossible to sort out the complex causal connections that underlie these patterns of elite-mass linkages. It is fruitless to ask which came first—the leaders' commitment to equality or the citizens' commitment to engagement. We cannot say in what measure the leaders are simply responding to the competence and civic enthusiasm (or lack of it) of their constituents, and in what measure civic engagement by citizens has been influenced by the readiness (or reluctance) of elites to tolerate equality and encourage participation. Elite and mass attitudes are in fact two sides of a single coin, bound together in a mutually reinforcing equilibrium.

In Chapter 5 we shall present evidence that these distinctive elite-mass linkages have evolved over a very long time. Under these circumstances, it would be surprising if elite and mass attitudes were not congruent. A situation of authoritarian elites and assertive masses cannot be a stable equilibrium, and a pattern of obeisant leaders and complaisant followers is hardly more permanent. The more stable syndromes of elite-mass linkages that we have actually found deepen our understanding of the dynamics of politics in civic and less civic regions. The effectiveness of regional government is closely tied to the degree to which authority and social interchange in the life of the region is organized horizontally or hierarchically. Equality is an essential feature of the civic community.52

Political leaders in civic regions are also readier to compromise than their counterparts in less civic regions. As we shall shortly see, there is no evidence at all that politics in civic regions is any less subject to conflict and controversy, but leaders there are readier to resolve their conflicts. Civic regions are characterized, not by an absence of partisanship, but by an openness of partisanship. This important contrast between civic and less civic politics is reflected in Figure 4.11, which reports the responses of councilors in our four surveys over two decades to the following proposition: "To compromise with one's political opponents is dangerous because that normally leads to the betrayal of one's own side." Of political leaders in the most civic region, only 19 percent agreed—less than half the rate among politicians in the least civic regions. Politicians in civic regions do not deny the reality of conflicting interests, but they are unafraid of creative compromise.53 This, too, is part of the tapestry of the civic community that helps explain why government there works better. The civic community is defined operationally, in part, by the density of local cultural and recreational associations. Excluded by that definition, however, are three important affiliations for many Italians—unions, the Church, and political parties. The civic context turns out to have distinctive effects on membership in these three different sorts of organizations.

Unions

In many countries (particularly those with "closed shop" provisions), union membership is essentially involuntary, and thus has little civic significance. In Italy, however, union membership is voluntary and signifies much more than merely holding a particular job.54 The ideological fragmentation of the Italian labor movement offers a wide choice of political affiliations—Communist, Catholic, neo-Fascist, socialist, and none-ofthe-above. White collar and agricultural unions are more important in Italy than in many other countries, expanding further the opportunities for membership. Salvatore Coi concludes that "political motivation and ideological tradition" are more important than economic structure in determining union membership in Italy.55 As a result, union membership has greater civic significance in Italy than it might elsewhere.

Union membership is much more common in the more civic regions. In fact, union membership is roughly twice as high in the more civic regions, controlling for the respondent's occupation: Among blue-collar workers, among farmers, among professionals, among self-employed businessmen, and so on, membership in unions is consistently higher in the more civic regions. By contrast, union membership is unrelated to education, age, and urbanization, and the differences by social class are less than one might expect. Union membership is almost as common among professionals and executives in civic regions as among manual workers in less civic regions.56 The civic context is almost as important as socioeconomic status in accounting for union membership in Italy. In the civic regions, solidarity in the workplace is part of a larger syndrome of social solidarity.57

The Church and Religiosity

Organized religion, at least in Catholic Italy, is an alternative to the civic community, not a part of it. Throughout Italian history, the presence of the Papacy in Rome has had a powerful effect on the Italian Church and its relationship with civic life. For more than thirty years after Unification, the Papal non expedit forbade all Catholics from taking part in national political life, although after World War II the Church became a senior partner of the Christian Democratic party. Despite the reforms of the Second Vatican Council and the flowering of many divergent ideological tendencies among the faithful, the Italian Church retains much of the heritage of the Counter-Reformation, including an emphasis on the ecclesiastical hierarchy and the traditional virtues of obedience and acceptance of one's station in life.58 Vertical bonds of authority are more characteristic of the Italian Church than horizontal bonds of fellowship.

At the regional level, all manifestations of religiosity and clericalism— attendance at Mass, religious (as opposed to civil) marriages, rejection of divorce, expressions of religious identity in surveys—are negatively correlated with civic engagement. (Figure 4.12 summarizes this pattern.) At the individual level, too, religious sentiments and civic engagement seem to be mutually incompatible. Of those Italians who attend Mass more than once a week, 52 percent say they rarely read a newspaper and 51 percent say they never discuss politics; among their avowedly irreligious compatriots, the equivalent figures are 13 percent and 17 percent.59 Churchgoers express greater contentment with life and with the existing political regime than other Italians. They seem more concerned about the city of God than the city of man.

In the first two decades after World War II, many Italians joined Catholic Action, a federation of Catholic lay associations reinvigorated by the Church as it sought to stay in tune with newly democratic Italy. The largest mass organization in Italy at that time, Catholic Action at its peak enrolled nearly a tenth of all Italian men, women, and children in its network of cultural, recreational, and educational activities. This membership had a regional distribution almost the reverse of that depicted for clericalism in Figure 4.12. Catholic Action was two or three times stronger in the northern, civic, more association-prone regions of the North than in the less civic areas of the Mezzogiorno. In that geographic sense, Catholic Action represented the "civic" face of Italian Catholicism. In the 1960s, however, with the rapid secularization of Italian society and turmoil within the Church following the Second Vatican Council, Catholic Action collapsed catastrophically, losing two-thirds of its members in just five years and leaving hardly a trace by the period of our study.60 In today's Italy, as in the Italy of Machiavelli's civic humanists, the civic community is a secular community.

Parties

Italian political parties have ably adapted to the contrasting contexts within which they operate, uncivic as well as civic. As a result, citizens of less civic regions are as engaged in party politics and as interested in politics as citizens of more civic regions.61 Membership in political parties is virtually as common in the least civic regions as in the most civic. Voters in less civic regions are as likely to feel close to a party as those in more civic regions. They talk politics as often as citizens in civic regions, and as we have seen, they are actually much more likely to have personal contacts with political leaders. Citizens of the less civic regions are not less partisan or "political."62

Party membership and political involvement, however, have a distinctive meaning in the less civic regions. It was above all in the Mezzogiorno that the "PNF" printed on party cards in the Fascist era was commonly said to stand not for Partito Nazionale Fascista [National Fascist Party], but per necessità familiare ["for family necessity"]. Winning favor from the powerful remains more important in less civic regions. "Connections" are crucial to survival here, and the connections that work best are vertical ones of dependence and dominion rather than horizontal ones of collaboration and solidarity. As Sidney Tarrow describes the impoverished, uncivic Mezzogiorno: "Political capacity in southern Italy is highly developed. . . . [The individual] is at once both highly political and resistant to horizontal secondary association. In this sense, all his social relations are 'political.'"63 Political parties are salient organizationally even in the less civic regions, despite the paucity of secondary associations, because all parties in that context have tended to become vehicles for patron-client politics. As we observed earlier, it is not the degree of political participation that distinguishes civic from uncivic regions, but its character.

Civic Attitudes

For all their politicking, citizens of less civic regions feel exploited, alienated, powerless. Figure 4.13 shows that (against a reasonably high background level of alienation among all Italians) both low education and uncivic surroundings accentuate feelings of exploitation and powerlessness. Index of Powerlessness

In every community, the more educated feel more efficacious, for education represents social status, personal skills, and connections. Nevertheless, even these advantages cannot fully compensate for the cynicism and alienation that pervade the less civic regions of Italy. Educated citizens in the least civic regions feel almost as impotent as less educated citizens in the most civic regions. Figure 4.13 also shows that community context has an even sharper effect on efficacy among the less educated than among the more educated. Class differences in powerlessness are heightened in the less civic regions.64 We do not need to construct tortured psychodynamic interpretations of this disaffection. By contrast with the more egalitarian, cooperative civic community, life in a vertically structured, horizontally fractured community produces daily justification for feelings of exploitation, dependency, and frustration, especially at the bottom of the social ladder, but also on somewhat higher rungs.

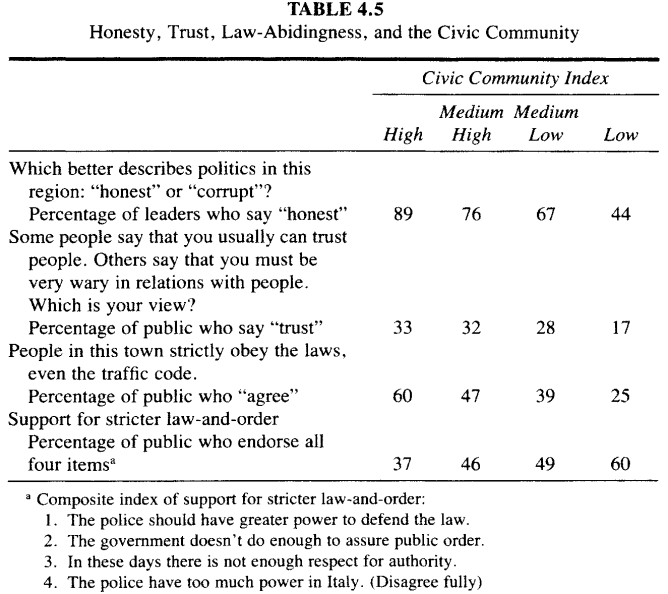

Honesty, trust, and law-abidingness are prominent in most philosophical accounts of civic virtue. Citizens in the civic community, it is said, deal fairly with one another and expect fair dealing in return. They expect their government to follow high standards, and they willingly obey the rules that they have imposed on themselves. In such a community, writes Benjamin Barber, "Citizens do not and cannot ride for free, because they understand that their freedom is a consequence of their participation in the making and acting out of common decisions."65 In a less civic community, by contrast, life is riskier, citizens are warier, and the laws, made by higher-ups, are made to be broken.

This account of the civic community sounds noble, perhaps, but also unrealistic and even mawkish, echoing some long-forgotten high school civics text. Remarkably, however, evidence from the Italian regions seems consistent with this vision. The least civic regions are the most subject to the ancient plague of political corruption. They are the home of the Mafia and its regional variants.66 Although "objective" measures of political honesty are not easily available, we did ask our nationwide sample of community leaders to judge whether politics in their respective regions was more honest or more corrupt than the average region. Leaders in the less civic regions were much more likely to describe their regional politics as corrupt than were their counterparts in more civic regions. Analogous contrasts emerged from our 1987 and 1988 surveys of mass publics throughout the peninsula, as illustrated in Table 4.5. Citizens in civic regions expressed greater social trust and greater confidence in the law-abidingness of their fellow citizens than did citizens in the least civic regions.67 Conversely, those in the less civic regions were much more likely to insist that the authorities should impose greater law-and-order on their communities.68

These remarkably consistent differences go to the heart of the distinction between civic and uncivic communities. Collective life in the civic regions is eased by the expectation that others will probably follow the rules. Knowing that others will, you are more likely to go along, too, thus fulfilling their expectations. In the less civic regions nearly everyone expects everyone else to violate the rules. It seems foolish to obey the traffic laws or the tax code or the welfare rules, if you expect everyone else to cheat. (The Italian term for such naive behavior is fesso, which also means "cuckolded.") So you cheat, too, and in the end everyone's dolorous, cynical expectations are confirmed.

Lacking the confident self-discipline of the civic regions, people in less civic regions are forced to rely on what Italians call "the forces of order,'' that is, the police. For reasons we shall explore in greater detail in Chapter 6, citizens in the less civic regions have no other resort to solve the fundamental Hobbesian dilemma of public order, for they lack the horizontal bonds of collective reciprocity that work more efficiently in the civic regions. In the absence of solidarity and self-discipline, hierarchy and force provide the only alternative to anarchy.

In the recent philosophical debate between communitarians and liberals, community and liberty are often said to be inimical. No doubt this is sometimes true, as it was once in Salem, Massachusetts. The Italian case suggests, however, that because citizens in civic regions enjoy the benefits of community, they are able to be more liberal. Ironically, it is the amoral individualists of the less civic region who find themselves clamoring for sterner law enforcement. Yet the vicious circle winds tighter still: In the less civic regions even a heavy-handed government—the agent for law enforcement—is itself enfeebled by the uncivic social context. The very character of the community that leads citizens to demand stronger government makes it less likely that any government can be strong, at least if it remains democratic. (This is a reasonable interpretation, for example, of the Italian state's futile anti-Mafia efforts in Sicily over the last half century.) In civic regions, by contrast, light-touch government is effortlessly stronger because it can count on more willing cooperation and self-enforcement among the citizenry.

The evidence we have reviewed strongly suggests that public affairs are more successfully ordered in the more civic regions. It is not surprising, therefore, that citizens in civic regions are happier with life in general than are their counterparts in less civic regions. In a series of nationwide surveys between 1975 and 1989, roughly twenty-five thousand people were asked whether they were "very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied with the life you lead." Figure 4.14 shows that citizens of civic regions are much more satisfied with life. Happiness is living in a civic community. At the individual level, life satisfaction is best predicted by family income and by religious observance, but the correlation with the civic community is virtually as strong as these personal attributes.69 Civic community is so closely correlated with both institutional performance and regional affluence that it is statistically difficult to distinguish among them although, of the three, civic-ness is marginally the best predictor of life satisfaction. In any event, as we shall discuss in more detail in succeeding chapters, these three features of community life have come to form a closely interconnected syndrome. Figure 4.14 shows that the character of one's community in this sense is as important as personal circumstance in producing personal happiness.

The contrast between more civic and less civic communities that emerges from these serried rows of data is, in many respects, quite consistent with the speculations of political philosophers. In one important respect, however, our story contradicts most classical accounts. Many theorists have associated the civic community with small, close-knit, premodern societies, quite unlike our modern world—the civic community as a world we have lost.70

Contemporary social thought has borrowed from the nineteenthcentury German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies the distinction between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft—that is, between a traditional, smallscale, face-to-face community resting on a universal sense of solidarity and a modern, rationalistic, impersonal society resting on self-interest. This perspective leads readily to the view that the civic community is an atavism destined to disappear. In its place arise large, modern agglomerations, technologically advanced, but dehumanizing, which induce civic passivity and self-seeking individualism. Modernity is the enemy of civility.

Quite the contrary, our studies suggest. The least civic areas of Italy are precisely the traditional southern villages. The civic ethos of traditional communities must not be idealized. Life in much of traditional Italy today is marked by hierarchy and exploitation, not by share-and-sharealike. James Watson, a close observer of Calabria, the toe of Italy's boot and the least civic of all twenty regions, stresses the lack of civic trust and associations:

The first quality that strikes an observer in Calabria is diffidence; not just diffidence towards the outsider but also within the community, even in small villages. Trust is not a commodity in great supply. . . . Historically, civil society has been almost totally lacking in associations apart from the occasional village or town social club (Circolo della Caccia, dei Nobili etc.).71

Conversely, at the top of the civic scale Emilia-Romagna is far from a traditional "community" in the classic sense—an intimate village as idealized in our folk memory. On the contrary, Emilia-Romagna is among the most modern, bustling, affluent, technologically advanced societies on the face of the earth. It is, however, the site of an unusual concentration of overlapping networks of social solidarity, peopled by citizens with an unusually well developed public spirit—a web of civic communities. Emilia-Romagna is not populated by angels, but within its borders (and those of neighboring regions in north-central Italy) collective action of all sorts, including government, is facilitated by norms and networks of civic engagement. As we shall see in Chapter 5, these norms and networks have vital roots in deep regional traditions, but it would be nonsense to classify Emilia-Romagna as a "traditional" society. The most civic regions of Italy—the communities where citizens feel empowered to engage in collective deliberation about public choices and where those choices are translated most fully into effective public policies—include some of the most modern towns and cities of the peninsula. Modernization need not signal the demise of the civic community.

We can summarize our discoveries so far in this chapter rather simply. Some regions of Italy have many choral societies and soccer teams and bird-watching clubs and Rotary clubs. Most citizens in those regions read eagerly about community affairs in the daily press. They are engaged by public issues, but not by personalistic or patron-client politics. Inhabitants trust one another to act fairly and to obey the law. Leaders in these regions are relatively honest. They believe in popular government, and they are predisposed to compromise with their political adversaries. Both citizens and leaders here find equality congenial. Social and political networks are organized horizontally, not hierarchically. The community values solidarity, civic engagement, cooperation, and honesty. Government works.72 Small wonder that people in these regions are content!

At the other pole are the "uncivic" regions, aptly characterized by the French term incivisme.73 Public life in these regions is organized hierarchically, rather than horizontally. The very concept of "citizen" here is stunted. From the point of view of the individual inhabitant, public affairs is the business of somebody else—i notabili, "the bosses," "the politicians"—but not me. Few people aspire to partake in deliberations about the commonweal, and few such opportunities present themselves. Political participation is triggered by personal dependency or private greed, not by collective purpose. Engagement in social and cultural associations is meager. Private piety stands in for public purpose. Corruption is widely regarded as the norm, even by politicians themselves, and they are cynical about democratic principles. "Compromise" has only negative overtones. Laws (almost everyone agrees) are made to be broken, but fearing others' lawlessness, people demand sterner discipline. Trapped in these interlocking vicious circles, nearly everyone feels powerless, exploited, and unhappy. All things considered, it is hardly surprising that representative government here is less effective than in more civic communities. This discovery poses two new and important questions: How did the civic regions get that way? and How do norms and networks of civic engagement undergird good government? We shall address those questions in the two chapters that follow, but first a few words about other potential explanations for the success and failure of the regional governments.

OTHER EXPLANATIONS FOR INSTITUTIONAL SUCCESS?

Social disharmony and political conflict are often thought inimical to effective governance. Consensus is said to be a prerequisite for stable democracy. This view has a distinguished lineage. Cicero wrote that "the commonwealth, then, is the people's affair; and the people is not every group of men, associated in any manner, but is the coming together of a considerable number of men who are united by a common agreement about law and rights and by the desire to participate in mutual advantages."74 Shaken by the specter of social conflict in revolutionary France, Edmund Burke suggested that the well ordered society must be considered a partnership, "a partnership in all science, a partnership in all art, a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection."75

This viewpoint has commanded many distinguished advocates among twentieth-century social scientists as well. Gabriel Almond praised the "homogeneous" political culture of "Anglo-American" political systems and described the fragmented "Continental" type of political system as "associated with immobilism" and ever threatened by "Caesaristic breakthrough."76 Giovanni Sartori argued that ideological polarization and fragmentation are characteristic of ineffective, "breakdown-prone" democracies.77 The greater the cleavages in a society or polity, the more difficult it will be to compose a stable government resting on the consent of the governed. The greater the disagreement on issues of substance, the less likely that any coherent program will be pursued: "If everyone had the same political preferences, the task of making policy would be much easier."78

This presumed association between social cohesion, political harmony, and good government appears, often implicitly, in many accounts of the civic community:

For Rousseau and for classical republicans generally, [patriotic feeling and political participation] rested and could only rest on social, religious, and cultural unity. They were the political expressions of a homogeneous people. One might say that, for them, citizenship was only possible where it was least necessary, where politics was nothing more than the extension into the public arena of a common life that began and was sustained outside.79

Such sentiments suggested for our research a variety of hypotheses about how social unity and political consensus might be linked to institutional performance. Sad to say, our expectations were thoroughly confounded. The success or failure of Italy's regional governments was wholly uncorrelated with virtually all measures of political fragmentation, ideological polarization, and social conflict:

• We examined the ideological polarization of the party system—measured both by party strength and by the views of regional leaders—suspecting that the greater the gulf between left and right, and the more powerful the voices of extremism, the more difficult it might be to compose an effective government.

• We examined the distribution of voters' views on key social and economic issues, presuming that the weaker the consensus on important policy matters, the more difficult government leaders might find it to forge a coherent strategy.

• We examined the fragmentation of the regional party system, believing that a multiplicity of small, fractious parties might impede government stability.

• We examined data on economic conflicts, such as strike rates, expecting that social tensions might thwart government effectiveness.

• We examined the geographic disparities in economic development and demography within each region, thinking that extremes of modernity and backwardness, or tensions between a large metropolis and surrounding rural areas, might make governing more difficult.

• We asked community leaders to rate their regions from "conflictful" to "consensual," and we matched their reports against our measures of institutional performance, presuming that where conflicts were salient, cooperation for common purposes would be arduous and governance might suffer.

None of these investigations, however, offered the slightest sustenance for the theory that social and political strife is incompatible with good government. We observed regions of high performance and low conflict, such as Veneto, but we also found successful, conflictful regions, such as Piedmont. We observed unsuccessful, conflict-ridden regions, such as Campania, but we also discovered consensual regions whose governments have performed below the national average, such as Basilicata.

Implicit in these conclusions is also the fact that we found no correlation between conflict and the civic community. The civic community is by no means harmonious and distinctively strife-free. Benjamin Barber's vision of "strong democracy" captures the character of the civic community as it emerges from our Italian explorations:

Strong democracy rests on the idea of a self-governing community of citizens who are united less by homogeneous interests than by civic education and who are made capable of common purpose and mutual action by virtue of their civic attitudes and participatory institutions rather than their altruism or their good nature. Strong democracy is consonant with—indeed it depends upon—the politics of conflict, the sociology of pluralism, and the separation of private and public realms of action.80

Several other possible explanations for institutional performance also failed to pass muster when confronted with evidence from the Italian regional experiment:

• Social stability has sometimes been associated with effective governance. Rapid social change, it has been argued, increases social strain, dissolves social solidarity, and disrupts existing norms and organizations that buttress government. Our preliminary analysis of regional performance through 1976 had found tentative evidence that demographic instability and social change inhibited performance,81 but this relationship disappeared in our subsequent, fuller analysis of performance and social change.

• Education is one of the most powerful influences on political behavior almost everywhere, including Italy. Nevertheless, contemporary educational levels do not explain differences in performance among the Italian regions. The correlation between institutional performance and the fraction of the regional population who attended school beyond the minimum school-leaving age of fourteen is insignificant. Emilia-Romagna, the highest-performing, most civic region, and Calabria, the lowest-performing, least civic region, have virtually identical scores on this measure of educational attainment (46 percent vs. 45 percent).82 Historically, education may have played an important role in strengthening the foundations for the civic community, but it seems to have no direct influence on government performance today.

• Urbanism might be thought relevant, in some form, to institutional performance. One version of this hypothesis recalls Marx's epithet about the idiocy of rural life and suggests that successful institutions might be positively associated with urbanization. An alternative folk theory, already alluded to, sees civic virtue in traditional villages and vice in the city. This theory implies that institutional performance should be lower in more urban regions. A more subtle theory would tie institutional performance (and perhaps the civic community) specifically to medium-sized cities, spared the anonymity of the modern metropolis, as well as the isolation of the countryside. In fact, however, we found no association of any sort between city size or population density and the success or failure of the regional governments.83

• Personnel stability marks the high-performance institution, according to some theories of institutionalization. Low turnover signifies that the members are committed to the institution and its success. Personnel stability also ensures a supply of experienced policymakers. High personnel turnover, especially in the early years of an institution, is said to engender precarious transitions.84 After examining detailed records for our six selected regions, however, we found no positive correlation between institutional success and personnel stability in either the regional council or the cabinet. The two regional councils with the lowest mean tenure over the entire 1970-1988 period were Emilia-Romagna and Veneto, which achieved virtually the highest ratings on our evaluation of institutional performance. "Fresh" leadership may be as important as "seasoned" leadership in explaining which institutions succeed.

• The Italian Communist party (PCI) has sometimes been given credit for the strong performance of certain regions. Certainly in a descriptive sense, our evidence is consistent with the judgment, widely held across party lines in Italy, that Communist regions are better governed than most others. Sometimes this is attributed to a rational, competitive calculation on the part of the PCI that it could best establish its credentials as a national party of government by showing how well it could rule regionally and locally. A more cynical alternative sometimes offered is that the PCI has, despite itself, been spared the corrupting effects of national power. Communists themselves attribute their "businesslike" successes to a systematic effort to recruit competent cadres or even to superior morality. Each of these interpretations contains a grain of truth, although we are most attracted by the first. Our initial analysis covering the 1970-1976 period suggested that this difference was due entirely to the fact that the Communists had come to power in unusually civic regions. "Communist regional governments were more successful [we argued] because they tilled more fertile soil, not because of their techniques of plowing. It is not who they were, but where they were, that counted."85 Our subsequent analysis, however, suggests that this might not be the whole story. After 1975, Communists joined ruling coalitions in several regions less favored by civic tradition, and performance in those regions tended in fact to improve. By the time of our later, fuller evaluation of institutional performance, the correlation between PCI power and institutional performance was not entirely attributable to covariance with the civic community.86 On the other hand, during the period of our research, the Communists remained in opposition in virtually all those regions, mainly in the South, where the civic and economic conditions are most detrimental to effective governance. Only when the PCI (now re-baptized the "Democratic Party of the Left") gains power in adverse circumstances of that sort will it be possible finally to evaluate the claim that party control makes a difference for good government.87

With the possible, partial exception of PCI rule, none of these supplementary explanations adds anything at all to our understanding of why some governments work and others do not. The evidence reviewed in this chapter is unambiguous: Civic context matters for the way institutions work. By far the most important factor in explaining good government is the degree to which social and political life in a region approximates the ideal of the civic community. Civic regions are distinctive in many respects. The next question is this: Why are some regions more civic than others?

'Political Science' 카테고리의 다른 글

| DEMOCRACY'S THIRD WAVE (0) | 2022.10.15 |

|---|---|

| Making Democracy Work_ Civic Traditions in Modern Italy(Ch.5) (0) | 2022.10.07 |

| SOME SOCIAL REQUISITES OF DEMOCRACY: ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND POLITICAL LEGITIMACY (1) | 2022.10.05 |

| Exclusion and Cooperation in Diverse Societies: ExperimentalEvidence from Israel (0) | 2022.10.05 |

| Using Qualitative Information to Improve CausalInference (0) | 2022.10.04 |