고정 헤더 영역

상세 컨텐츠

본문 제목

4. Power Concentration : The Effect of Elite Factionalism on Personalization

본문

Islam Karimov, Soviet Uzbekistan’s last Communist Party leader, remained in power after 1991, to become independent Uzbekistan’s first dictator. The rest of the Uzbek political elite at independence had also spent their careers in the Communist Party. There had been no nationalist uprising in Uzbekistan. Russian-officered Soviet troops were still stationed in the country, and the KGB managed internal security (Collins 2006, 173). Indeed, many observers saw the Karimov regime as a simple continuation of Communist Party rule under a new name.

Yet, even before formal independence, Karimov had eliminated the Communist Party of Uzbekistan (CPU) as the institutional base for the regime and taken personal control of the security services and high-level appointments previously controlled by the party. Karimov retained the support of most of Uzbekistan’s pre-independence elite despite destroying the formal underpinnings of their political power because the informal bases of their power remained intact. Regionally based loyalty networks, usually referred to as clans, continued to structure political bargaining and decision-making as they had during communist rule.

When first appointed, Karimov was weak; he was not a clan leader or an important figure in the ruling party (Carlisle 1995, 196, 255; Collins 2006, 118–23). The most influential Uzbek clans had consolidated their informal control during Soviet rule by infiltrating and coopting the CPU, which enabled them to take over party and government patronage networks along with different parts of the state-owned economy. Gorbachev’s earlier efforts to clean up corruption and limit clan power had failed, and he had bowed to political necessity in appointing a new CPU general secretary supported by the most powerful clans. Clan leaders backed Karimov because they distrusted one another. Karimov lacked an independent power base and needed the clan leaders’ support to retain power, so he was expected to be responsive to their demands (Collins 2006, 122–23; Ilkhamov 2007, 74–76). Clan leaders “thought of him as their puppet” (Carlisle 1995, 196).

When Karimov was appointed first secretary, he “needed to demonstrate sensitivity to local elite interests, and to maintain a balance of power amongst the various significant clan actors . . . Even though he did not trust certain clan or regional factions,” he incorporated “at least token members of each regional elite into the new government” (Collins 2006, 128). He had to share the most with the clan leader most eager to replace him, whom he appointed first as prime minister and then as vice president (Carlisle 1995, 196, 198; Collins 2006, 129). Supporters of the vice president dominated the Supreme Soviet.

As of early 1991, Karimov somewhat precariously controlled the CPU and government by balancing and juggling competing clan interests. He lacked a Soviet patron, and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was disintegrating. Karimov had to choose political and economic strategies to “retain all the major [clan] players in the pact” (Collins 2006, 193). One observer described his governing style as “consensual” (Ilkhamov 2007, 75, 78).

All clans included in the pact benefited from the regime, but they nevertheless competed fiercely over high-level posts and the opportunities to make profits and strip state assets that came with appointments. The clans’ mutual antagonism provided Karimov with opportunities for power grabs at the expense of particular clans, despite his need to maintain the support of most of them. On the heels of the Soviet coup attempt, Karimov banned the CPU and seized its assets, in part to reduce the resources and power of the Supreme Soviet. Banning the party stripped many deputies of their privileged access to jobs as members of the nomenklatura. He then created a new government-support party, the National Democratic Party of Uzbekistan, led by himself. It never controlled the resources the CPU had, however, or dominated politics and controlled appointments. In the future, legislative nominations would be vetted not by the party but by Karimov personally, reducing the power of the legislature (Collins 2006, 194–95, 253, 257). Outlawing the CPU shifted the balance of power between Karimov and others in the ruling elite sufficiently for him to abolish the office of vice president, arrest some of the vice president’s allies, and thus rid himself of his most threatening supporter. Other clans did not defend those excluded or arrested.

“The result of [Karimov’s] policies from 1990 through 1993 was the gradual transformation from a communist regime to an autocratic one, in which power belonged not to a hegemonic party, but to Karimov himself and the clique of clan elites who surrounded him” (Collins 2006, 198). A feature of the postSoviet context that aided Karimov’s power grab is that he was not threatened militarily. The clans had not penetrated the military stationed in Uzbekistan or the KGB because Russians controlled both, and none of the clans had its own militia.

In the wake of the Soviet coup attempt, Karimov increased his control of security forces. He shifted resources to the presidential guard and the Committee for Defense, which he had created a few months before to counterbalance the Soviet troops stationed in Uzbekistan. He also put Soviet military forces under the highest-ranking Uzbek officer’s command (Collins 2006, 162) and appointed a close ally from his own clan to lead the internal security agency. From then on, Karimov kept the presidential guard, army, and internal security agency “under his close supervision and control” (Collins 2006, 274).

Through the early 1990s, Karimov continued juggling multiple clan supporters, mostly by distributing state-controlled economic opportunities among them. “[W]ith a tenuous political pact supporting him, Karimov had no choice but to engage in a negotiating process with various factions” (Collins 2006, 257). On the civilian side, he used his “political budget,” funded largely by the export of cotton, gold, and oil along with the drug trade, to secure support (Collins 2006, 262–67; De Waal 2015). In contrast to the dictators described by De Waal (2015), however, he had a near-monopoly on the means of violence. Members of Karimov’s clan staffed the internal security agency. In the military, Russian officers were purged and usually returned to Russia, while politically motivated promotions and dismissals solidified the loyalties of Uzbek officers (Collins 2006, 274).

In the mid-1990s, Karimov began incrementally eliminating some of his erstwhile allies from the inner circle. “Gradually, he consolidated power under his personal control and loosened his dependence on his previous allies and partners” (Ilkhamov 2007, 76). For example, the all-important head of cadre policy, a representative of one of the most powerful clans, was arrested in 1994. Karimov transferred the head of the Uzbek KGB, a man from his own clan, to a less important post in 1995, and created a second security service so that the two could report on each other (Collins 2006, 263).

Nevertheless, most clans continued to support Karimov in exchange for the vast economic opportunities made possible by continued state ownership of much of the economy. The Jurabekov clan linked to Samarkand, for example, controlled oil and gas, many of the bazaars, and the cotton complex. The Alimov clan from Tashkent controlled much of the banking system, the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations, the tax inspectorate, the general procurator, a share of the dollar trade, and most import-export businesses. Less powerful clans controlled less, and a few were entirely excluded (Collins 2006, 264–68). The monopoly rents, black market currency dealing, asset stripping, and widespread corruption facilitated by clan control of the economy, however, led to slow growth, increased poverty, and rising inequality.

By the late 1990s Karimov was “locked in an ongoing struggle to maintain and increase his own personal autocratic control and to hold together powerful regional and clan elites without allowing them to strip the state of its capacity to survive” (Collins 2006, 170). He dismissed or demoted the prime minister, defense minister, and several members of the inner circle from the Ferghana network without political consequences. In 1998, Karimov dismissed Jurabekov, Uzbekistan’s most powerful clan leader, along with many other members of his network. A few months later, however, Karimov reinstated Jurabekov after an assassination attempt attributed to him (Collins 2006, 170–71). Though Karimov narrowly escaped assassination, the attempt demonstrated the Jurabekov clan’s credible threat to oust the dictator if he failed to share with them, and he promptly reinstated them. However, the other clans did not make similarly credible threats and therefore could not prevent power grabbing at their expense.

As Karimov excluded important members of the original inner circle from office and benefits, members of his own family took control of key sectors of the economy. “Step by step, the major export resources were concentrated in the hands of the central government, under the President’s personal control” (Ilkhamov 2007, 76). By the early 2000s, the family controlled the major state telecoms company, gold mining, and part of the oil business (Collins 2006, 170–71). In 2006, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported that Karimov had “chip[ped] away at the political and economic might of some of Uzbekistan’s most influential clans.” Jurabekov was dismissed once more in 2004 and accused of corruption. This time he did not return to the inner circle. The defense minister was forced to resign in 2005 and tried for corruption and abuse of office. About 200 families had grown very rich under Karimov’s original system of power sharing, but the circle of beneficiaries became smaller and smaller in the 2000s, as it narrowed to not much more than the Karimov family.

Until his natural death in 2016, Karimov remained “a master at maneuvering among the various clans in Uzbekistan and playing them off one another” (Panier 2016). He retained control by balancing the clans, allowing no single one to become too powerful, and rotating ministers, governors, and other appointments frequently to prevent officials from building their own support networks from which to challenge him (Saidazimova 2005; Ilkhamov 2007, 77; Panier 2016). Nevertheless, “[c]ompeting regional and clan factions trusted Karimov more than they trusted each other, and hence preferred to have him at the center” (Collins 2006, 261).

Uzbekistan’s experience raises the question: How can a political leader who seemed entirely dependent on the support of his country’s most powerful political forces concentrate power at their expense and without forfeiting their support? In this chapter, we explain how this happens. We show how factionalism in the ruling group – in Uzbekistan, their division into multiple competing clans – undermines power sharing and thus facilitates the emergence of oneman rule. This happens for two reasons. First, disunited ruling groups have difficulty making credible threats to oust the dictator and therefore cannot constrain him. And second, most members of the support group remain willing to support the dictator even when he unilaterally reduces their access to benefits because they are still better off inside the inner circle than excluded from it. In contrast, a united seizure group can constrain the dictator’s ability to concentrate power, as well as his policy and distributive discretion, because they can make credible threats to oust him if he fails to share.

The chapter begins with an overview of how bargaining works in dictatorships. It describes the central dilemma of new dictatorships: the colossal control problem caused by handing dictatorial power to one member of the ruling group. It explains our theory of how this problem affects bargaining between dictators and other members of the dictatorial elite and describes the central interests of both.

The second half of the chapter shows how preexisting characteristics of the seizure group affect its ability to make enforceable bargains with the new dictator. The dictator has little need to share or consult with his closest supporters if preexisting factions facilitate bargaining with them separately, as Karimov could with clan leaders. Bargaining separately induces competition among faction leaders, which drives down the price dictators have to pay for support. Based on these insights, we generate expectations about conditions that facilitate the concentration of power in the hands of one man, which we call “personalism.” We then explain how these informal bargaining relationships, established during the dictatorship’s first years, can become sticky over time. Last, we test these ideas using new data and show evidence consistent with our arguments.

Elite bargaining in dictatorships

In autocracies, a small number of regime insiders, usually acting in private under informal rules, hammer out key decisions about leadership and policy directions even in regimes with stable, well-developed formal institutions. The influence and authority of members of the dictatorial elite may be renegotiated frequently during the early years and subject to arbitrary and violent change. Dictatorial elites may ignore formal rules and institutions if they obstruct the drive to amass power. Losers in policy debates may be excluded from the inner circle, demoted, arrested, or even executed. Life in a dictatorial elite is thus insecure, dangerous, and frightening. Informal procedures may become institutionalized over time, meaning that they become both more predictable and costly to change, but for the first months or years after an autocratic seizure of power, bargaining within the dictatorial elite often occurs in an environment of contested, changing, and nonbinding institutions (Svolik 2012).

When making decisions about policy, leadership, and institutional choice, the dictator and members of his inner circle take into account expected effects of the choice on regime survival, but also how decisions may affect their individual power, influence, and access to resources. Members of dictatorial elites live in grim, dog-eat-dog worlds. Taking one policy position can provide the opportunity to take a bite out of another dog, while taking a different one could incite the pack to tear you apart. Autocratic policy makers, like democratic ones, may care deeply about the substance of policy, but they cannot afford to ignore how their decisions will affect regime survival and their personal survival as well.

To explain these decisions, we focus initially on the interests of members of the seizure group. Because the members of groups never share exactly the same interests, our theory begins with strategic interactions among them. We do not assume that seizure groups, or the regime elites that derive from them, are unitary actors because the empirical record shows that discipline among them is imperfect. How much discipline they can maintain requires empirical investigation. Consequently, neither the dictatorship’s inner circle as a whole nor any subset of it larger than one member should be assumed to behave as a unitary actor.

We do assume that members of the dictatorship’s inner circle want to maintain the dictatorship, which they expect to further their policy goals, as well as provide opportunities for personal advancement and often enrichment. However, they also want to increase their personal share of power relative to others in the inner circle. They must compete with each other for power, not only to improve their standing in the inner circle or their access to wealth, but also to maintain their current positions against lower-ranked regime supporters striving to replace them in the inner circle. An increase in power for one member of the inner circle comes at the expense of someone else. We see power as a rank ordering based on politically relevant resources, understood by insiders even when not perceptible to observers. One insider cannot move up the rank order without displacing someone else.

Because of the intense competition within the inner circle, we expect the dictatorship’s most powerful decision makers to consider how all policy, appointment, and institutional choices might affect their own standing, as well as regime maintenance. The creation of new formal institutions benefits the individuals who will lead them and those who will work in new agencies associated with their implementation. Policy choices also often entail the creation of new agencies, which, again, benefits those chosen to lead and work in them. Policies also have distributional consequences that advantage some and disadvantage others. They thus affect the welfare of the constituents of inner circle members differently. Consequently, we expect inner-circle members to favor policies and institutions that both improve their own place in the hierarchy and increase the likelihood of regime survival. However, both are impossible for everyone in the inner circle since any change that increases the powers of one member decreases those of others. Bargaining over policy thus has a noncooperative dimension, and strategic considerations often affect substantive policy choices (just as in democracies).

In other words, the dictator and inner circle engage simultaneously in two kinds of strategic interaction: (1) a cooperative effort aimed at keeping all of them (the regime) in power and (2) noncooperative interactions in which different members/factions seek to enhance their own power and resources at the expense of others in the inner circle. Each individual strives to amass resources and capacities up to the point at which his efforts would destabilize the regime or lead to his own exclusion from the inner circle.

The dictator has a resource advantage because he has the most direct access to state revenues and an information advantage because he has access to the reports of all internal security services. Nevertheless, the dictator faces the same dilemma as other members of the inner circle: he wants to extend and consolidate his control up to the point at which other members of the inner circle would take the risk of trying to oust him. The struggle over the distribution of power in a new dictatorship can transform the seizure group from the cooperative near-equals who had plotted the fall of the old regime into competitors in a vicious struggle for survival and dominance.

We see these incentives as common to all dictatorships, but they play out in different ways, depending on concrete characteristics of the seizure group that pre-date the installation of the dictatorship. We argue that preexisting differences among the groups that initiate dictatorship lead to post-seizure differences in what kinds of individuals with what interests become members of the dictatorial inner circle, how the inner circle makes decisions, which policies and institutions they choose, how they seek to attract members of society as allies, and how they respond to opposition. Preexisting characteristics of the seizure group do not determine everything that happens over the course of a dictatorship, but they do affect the likelihood that regimes will display specific, often long-lasting, patterns of behavior. The institutions chosen by dictatorial elites after they take power also have consequences for subsequent bargaining and the way dictatorships break down. That is their purpose, after all. Preexisting characteristics of the seizure group, however, influence the choice of these institutions.

We thus share with Svolik (2012) the view that all dictatorships face certain dilemmas, such as the dictator’s temptation to grab more power than his supporters want to delegate, but we emphasize that these dilemmas can have different outcomes, depending on characteristics of the seizure group that affect the bargaining power of different members of the group. In this chapter, we explain how one preexisting feature of seizure groups, their position on a continuum from factionalism to unity, affects authoritarian politics.

We provide greater detail in the sections that follow, beginning with the first decision seizure groups confront: selection of a leader.

Handing power to a leader

In order to govern, seizure groups must choose a leader (dictator). They need a leader to speak on behalf of the new government, represent it to the populace and foreign actors, organize the implementation of policies made by the group, coordinate their activities across agencies and levels of government, mediate conflicts within the inner circle, act in emergencies, and make final decisions when opinions in the group are divided. The point of choosing a leader is to achieve the goals of the group. However, the delegation of the powers needed to fulfill these responsibilities in the largely institution-free setting of early dictatorship causes the interests of the dictator to diverge from those of his closest allies. While the dictator hopes to defang his allies’ threats to oust him if he disregards their interests, they seek to hold the new dictator in check. This happens regardless of whether the dictator and his allies come from the same ethnic or other close-knit group. This divergence of interests creates the colossal problem of how to control a leader with dictatorial powers.

When the seizure group delegates powers to a leader, it does not intend to give him the capacity to choose policies most of them oppose, unilaterally exclude from the inner circle individuals who helped seize power, or dismiss, jail, or kill seizure-group members, their allies, and family members. These are highly visible depredations on the ruling group. The absence of binding limits and institutional checks on the dictator, however, mean that only credible threats to oust the dictator deter him from reneging on agreements and abusing his supporters (Magaloni 2008; Svolik 2012).

The dictatorial elite cannot costlessly dismiss the dictator. On the contrary, efforts to oust a dictator always involve a high risk of failure, followed by nearcertain exclusion from the ruling group and possible exile, imprisonment, torture, and/or execution. And yet the dictatorial elite can limit the dictator’s depredations only if they can credibly commit to ousting him if he seizes more power or resources than they have agreed to transfer.

Seizure groups should anticipate the possibility that the man chosen to lead could escape their control, since the dictator cannot make credible promises not to use his powers. Before they take power, some seizure groups try to hem in the dictator by making rules about who should help him make policy, how these lieutenants should be chosen, the periodic rotation of leadership, and how they will handle succession. When plotters come from professionalized militaries, which tend to be legalistic and rule-bound, they may negotiate quite detailed arrangements for term limits and consultation over policy choice within the officer corps (Fontana 1987). These rules can be enforced at the time they are agreed to because power is dispersedwithin the group. Themanwhowants to be leader must agree to power-sharing arrangements such as regular consultation or term limits in exchange for the support of other members of the seizure group.

Most dictators, like Karimov, are weak the day they become regime leader. Karimov needed support initially from several clan leaders and the Communist Party to stay in power, and thus had to distribute state offices and the resources they controlled among them. Military dictators are sometimes weak because they have had to retire from active duty, and thus give up the ability to control others’ promotions, postings, and retirements, in order to secure the support of others in the junta for their appointment as leader.

Bargains made when the dictator is weak, however, last only as long as they are self-enforcing because of the lack of third-party enforcement institutions in dictatorships (Barzel 2002, 257; Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson 2005, 429; Svolik 2012). The initiation of dictatorship creates immediate opportunities for changing the relative distribution of power within the seizure group. History is replete with examples of men who were invited to lead by plotters who believed they would be malleable figureheads, but who quickly marginalized and sometimes killed those who had expected to call the shots. Plotters sometimes consciously choose an individual considered uncharismatic and legalistic to reduce the likelihood of future concentration of power in his hands. It has been reported that Chilean plotters chose General Augusto Pinochet, a latecomer to the coup conspiracy, for that reason. He was quick to concentrate power in his own hands, however. Other examples include Major Mathieu Kérékou, who was invited by even more junior coup plotters to lead the 1972 seizure of power in Benin. Within three years, he had excluded the original plotters from government, apparently killing one and jailing several others (Decalo 1979; Allen 1988). After the 1975 coup in Bangladesh, junior officers and ex-officers released General Mohammad Zia ul-Hak from jail and appointed him Chief Martial Law Administrator because they feared the rest of the army would not acquiesce in the coup if a junior officer was appointed. Zia quickly excluded them from the ruling group, arrested those who tried to oust him for violating their initial bargain, and executed their leaders for treason (Codron 2007, 12–13).

This problem is not limited to military seizure groups. Malawi’s Hastings Banda, recruited as a presidential candidate by young civilian nationalists, not only excluded his youthful colleagues but quickly transformed the elected government he led into a highly repressive autocracy. Banda, a doctor who had been working outside the country for more than twenty years, was invited to lead by young independence leaders who “assumed he could not conceivably harbor any long-term political ambitions” (Decalo 1998, 59). After the founding election, he dismissed his young allies from their cabinet posts, forced them into exile, and purged the ruling party of anyone suspected of challenging his “unfettered personal rule” (Decalo 1998, 64), which then lasted for more than thirty years.

The frequency of this sequence of events suggests that control of the state, even as rudimentary a state as Malawi’s at independence, gives the paramount leader a resource advantage over his erstwhile colleagues. The new dictator finds himself “almost immediately in command of all the financial and administrative resources of the state” (Tripp 2007, 143). Becoming head of state gives the new dictator access to revenues – especially from taxes, the export of natural resources, and foreign aid – far greater than he has had before and greater than other members of the seizure group can command. This control endows the new dictator with agenda-setting power when it comes to policymaking and distributive decisions. Revenues can be shared with the inner circle or spent by the dictator to buy personal support and security. Further, access to state revenues gives the dictator substantial control over appointments to state offices, which he can use to bring loyalists into decision-making positions and to create state agencies to pursue goals not shared by the rest of the seizure group.

These revenues can enable the dictator to outmaneuver his allies. In some circumstances, he can buy the support of some members of the inner circle for the exclusion of others. He may even be able to buy their support for changes that further enhance his power at the expense of theirs. In short, a dictator who was first among equals on the day he was chosen has substantial potential to grab additional resources and power later.

We refer to dictatorships in which the leader has concentrated power at the expense of his closest supporters as personalist. The defining feature of personalist dictatorship is that the dictator has personal discretion and control over the key levers of power in his political system. Key levers of power include the unfettered ability to appoint, promote, and dismiss high-level officers and officials, and thus to control the agencies, economic enterprises, and armed forces the appointees lead. In such regimes, the dictator’s choices are relatively unconstrained by the institutions that can act as veto players in other dictatorships, especially the military high command and the ruling party executive committee. Personalist dictators juggle, manipulate, and divide and rule other powerful political actors. Like all dictators, they need some support, but they can choose from among competing factions which ones can join or remain in the ruling elite at any particular time. Personalist dictators are thus powerful relative to other members of the elite, but not necessarily relative to society or to international actors.

Islam Karimov’s rule exemplified personalism, especially in later years. His control of Uzbekistan’s political system derived from his appointment powers. Initially, he had to bargain with several clan leaders over the composition of his government and the control of all important state-owned enterprises and government agencies. Over time, however, he achieved much greater personal discretion over appointments, and most important clans continued supporting him despite losing some of their influence and access to income.

We argue that discretion such as Karimov’s arises from the dictator’s ability to bargain separately with supporters, to play them off against each other, to ally with some in order to damage or exclude others, and to bring previously excluded groups into the dictatorial inner circle in order to tip the balance of power in his favor when needed. The concentrated power wielded by personalist leaders is thus not absolute but rather depends on the dictator’s ability to use a changeable divide-and-rule strategy against supporters who could control or overthrow him if they could unite. The description of Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh as “dancing on the heads of snakes” captures this understanding of the personalist dictator as not necessarily the deadliest member of the ruling coalition but rather the one who can stay aloft by pitting some factions against others in an ever-changing balancing act (Clark 2010).

Personalism can rise and fall during a single dictator’s tenure, for reasons we describe later. (The data we use to measure personalism are coded yearly to capture these within-ruler and within-regime changes. They thus differ from our older regime-type coding, which could not capture these real-world variations.)

Since achieving the post of dictator requires great effort (as well as quite a bit of luck), we can infer that those who achieve it wanted it. Regardless of whether the job lives up to expectations, the danger inherent in giving it up predisposes dictators to try to hang on to power. Twenty percent of dictators are jailed or killed within the first year after losing office, while another fifth flee their native countries to avoid such consequences.

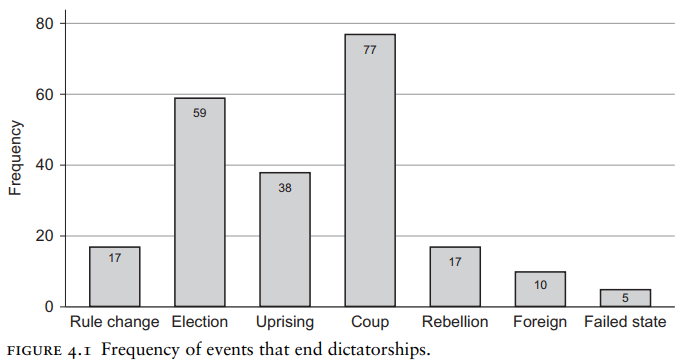

Dictators must fear their closest allies. Their careers can end in two ways other than natural death: the overthrow of the regime or the ouster of the dictator despite regime continuity. Members of dictatorial inner circles often lead ousters even when they also involve popular mobilization. Figure 4.1 shows the frequency of the various events that end dictatorial regimes, a subject we return to in Chapter 8. More dictatorships end in coups, that is, overthrows by the officers who were entrusted to defend them, than in other ways. Formerly powerful members of inner circles, however, have also led many popular uprisings and opposition election campaigns, the other common ways that autocracies end.

Only about half of dictator ousters accompany regime failures (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz 2014). The rest of the time, dictators are replaced but the regime survives. Regime insiders cause nearly all dictator replacements in surviving autocracies. Coups cause about a quarter of these. Eighty-five percent of such leader-shuffling coups replace one military dictator with another. Deaths, party decisions, and term limits enforced by the dictatorial inner circle account for most of the remaining three-quarters of dictator replacements in ongoing regimes. It is rare for popular action to oust a dictator without ending the dictatorship as well.

These basic facts about dictator ousters reveal the potential threat to the dictator posed by members of the inner circle (Svolik 2012; Roessler 2016). This threat gives the dictator an interest in closely scrutinizing his allies’ activities and dismissing, jailing, or killing them if he begins to suspect their loyalty. The dictator’s interest in limiting threats from the inner circle implies that members of the dictator’s support coalition today cannot count onbeing included in it tomorrow.9

To sum up, the average dictator has good reasons for wanting to retain power since he cannot count on a safe, affluent retirement if he steps down. Nor can he count on his family being left in peace and prosperity. The individuals most likely to be able to oust him are members of his inner circle. The dictator thus needs their support. Because promises can never be completely credible, however, the dictator has reason to spy on his allies to try to assess whether they are plotting behind his back. The dictator has every reason to try to build his own political resources at the expense of his allies, as he can never fully trust them. In other words, he has strong reasons to violate the implicit leadership contract by aggrandizing his own power.

The Interests of Other Members of the Inner Circle

Exclusion from the dictator’s inner circle can result in execution, torture, long imprisonment, property confiscation, exile, and poverty. Family members may have to bear these costs along with the target of the dictator’s suspicions. Consequently, constraining the dictator’s ability to exclude members from the inner circle ranks at the top of its members’ goals. Members of the inner circle also want to influence policy choices and build their own clientele networks, which are needed to secure their influence and acquire wealth. Some of them yearn to supplant the dictator. To accomplish these goals, they need to retain influence on decision making, and they need to obtain posts and promotions that entail both some policy discretion and the ability to hire, promote, and do favors for others. The opportunities available to members of the inner circle vary with the kind of posts they occupy.

The members of the dictator’s inner circle thus have strong reasons to want to maintain collegiality in decision-making and the dispersion of resources within the group, rather than allowing the dictator to usurp policy discretion and control over top appointments. These aims give members of the dictator’s inner circle good reasons to create institutions that enforce constraints on the dictator, and thus to prefer some institutional arrangements to others.

For example, members of the inner circle may demand term limits for the leader as a way of both limiting his ability to amass powers over time and increasing their own chances of occupying the top post in the future. In dictatorships led by a military officer, other officers in the inner circle also want him to retire from active duty, which establishes the credibility of his commitment not to use control over their promotions, retirement, and postings to concentrate power at their expense (Arriagada 1988; Remmer 1991). If the dictatorship is organized by a ruling party, members of the inner circle want party procedures for choosing its executive committee (politburo, standing committee) to be followed in spirit not just letter; they do not want the dictator personally to choose members of the party’s decision-making body since that would mean that he can exclude anyone who might disagree with him.

Members of the inner circle also favor an institutional arrangement that limits the dictator’s personal control over internal security forces. Preventing the dictator from gaining personal control over the internal security apparatus is important to the welfare of members of the inner circle. If a dictator controls the security police, he cannot credibly commit not to use it against his allies.

Conflict over the distribution of power between dictators and their supporters afflicts all new dictatorships. Many of the power struggles during the first months and years of dictatorship can be understood as efforts by the inner circle to control the dictator, efforts by the dictator to escape control, and efforts by both to institutionalize the relationship in order to reduce potentially regime-destabilizing conflict between them.

In this environment, everyone’s actions are somewhat unpredictable, prompting both the dictator and his lieutenants to remain on guard and trigger-happy. Furthermore, the unreliability of information increases the likelihood of misinterpreting the actions of others, opening the way to paranoia. Despite his information advantage over others in the inner circle, the dictator’s information about what they really think and what they may be planning remains limited and unreliable (Wintrobe 1998). For all these reasons, early periods in dictatorships tend to be unstable, conflictual, and sometimes bloody.

Bargaining over the distribution of resources and power

Earlier studies have emphasized the importance of whether the dictator can credibly commit to fulfill promises he makes (e.g., Magaloni 2008; Svolik 2012; Boix and Svolik 2013). Less attention has been paid to how much spoils and power the dictator really needs to share with his closest allies to retain their support. Here we ask: Assuming the dictator could credibly commit to sharing power, how much does he need to share? That is, how much power sharing does his personal survival require?

A dictator can reduce the amount he shares in two main ways: by reducing the number of supporters with whom he shares spoils and influence and by reducing the amount of power or influence he shares without decreasing the number of supporters. These two strategies often go together. Reducing the number of groups represented in the inner circle, and thus reducing the benefits received by the constituencies they represent, is easier for outsiders to observe than reductions in influence while the individuals who have lost some power remain part of the dictatorial elite. We discuss reducing the size of the ruling coalition first.

Seizure groups are often large when they take power. At the time of a coup, for example, many members of the officer corps must acquiesce in the seizure for it to succeed, even if they do not actively support it; “authoritarianization” can occur only after a party has attracted the support of most citizens in an election. A dictator may not need all this support to survive, however, because some members of the seizure group may lack the means to oust him.10 This means that the inner-circle members linked to some constituencies can be safely shed, and the dictator can keep their “share” (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003).

Bargaining between the dictator and others in the inner circle over the distribution of power and spoils begins when the dictator decides whether to stick to arrangements initially agreed to or renege on the implicit or explicit commitment to share and consult. The dictator controls some amount of goods and powers that both he and other members of the inner circle value highly. These can include access to material goods, such as the revenues from stateowned natural resources, as well as control over various aspects of policy and the choice of personnel to fill high and low offices. These goods are valuable, both to have and to dole out to clients. The dictator makes an initial decision about how to distribute these goods to best secure the adherence of needed supporters. His lieutenants expect to be consulted about these decisions and to receive a share, but their expectations may not be enforceable.

The dictator’s agenda-setting power gives him an advantage over those who can only react to proposals (Baron and Ferejohn 1989). Those whose only options are to accept or reject distributive proposals must make decisions about whether to continue supporting the dictator – based on a comparison between what the dictator offers and what they expect to receive if they withdraw from the ruling group. Once the dictator has demonstrated the way he intends to handle the resources he controls, other members of the inner circle can acquiesce in the distribution he proposes or contest it. If they could replace the dictator, they might do much better, but if they see the choice as lying between acceptance of what the dictator offers and exclusion from the ruling coalition (the consequence of rejecting the offer), they would be better off accepting even quite a small amount in exchange for their continued support. This logic leads to the counterintuitive conclusion that members of dictatorial elites may continue to support the dictator even if they receive only a little in return.

The capacity of the dictator’s allies to influence his distribution decisions (enforce their expectations) depends on the credibility of their threats to oust him. The dictator can always be removed by the united action of other elites. Sometimes he can be removed by small groups of them. Trying to remove dictators is risky, however, and no one plotting such a course can count on success. Terrible consequences can follow the discovery of plots. As a result, fewer allies plot than are dissatisfied with their share. The dictator thus reaps an additional bargaining advantage from the riskiness of plots. The more unlikely a plot’s success, the larger share a dictator can keep.

To summarize these points, all dictators need some support, which they must reward, but they need to offer only enough to maintain the minimum coalition required to stay in power. The other original members of the seizure group, and the parts of its larger support coalition associated with them, can be excluded without endangering the regime. There is a strong incentive to exclude them because the dictator can then keep their “share” or give it to others whose support he needs more. Remaining inner-circle members want to share spoils and power, but they still have little bargaining power besides the threat to replace the dictator. These conditions mean that the dictator can often get away with keeping the lion’s share for himself, just as the proposer in standard legislative bargaining games can (Baron and Ferejohn 1989).

This logic thus makes clear why members of authoritarian coalitions often acquiesce in the concentration of power and resources in the hands of dictators. Note that although Baron and Ferejohn’s (1989) result does not fit empirical reality in democratic legislatures very well – that is, prime ministers do not generally keep the lion’s share of resources – it is eerily similar to the reality of conspicuous consumption and Swiss bank accounts enjoyed by many dictators.

Characteristics that influence the credibility of threats to oust the dictator

So far we have treated members of the dictator’s inner circle as separate individual actors. A real inner circle might resemble this image if, for example, the leaders of multiple clans, parties, or ethnic groups, who had cooperated to throw out a previous regime or colonial power, formed the new ruling group. Militaries riven by ethnic, ideological, or personal factions may also contain many faction leaders who bargain individually rather than being subsumed in a single unified military bargainer. Parties colonized by clans, as in Uzbekistan, can also contain multiple faction leaders who bargain individually on behalf of their members. So can recently organized parties formed by coopting the leaders of older rival parties. In these circumstances, the dictator does in fact bargain with multiple separate actors, and threats to oust him are less credible because of the high risk of plots involving single factions and the difficulty of uniting the factions for joint action. As a result, the dictator can often concentrate resources and power in his own hands, as Karimov did.

Preexisting discipline and unity within the seizure group – from which the dictatorial inner circle is chosen – tilt post-seizure bargaining against the dictator, however. Internally cohesive seizure groups can bargain as something close to unitary actors over issues such as limitations on the dictator’s personal discretion. They also face fewer collective action problems when it comes to organizing the dictator’s overthrow. Disciplined unity develops in professionalized militaries and parties formed as “organizational weapons”. because these institutions transparently link individuals’ future career success to obedience to superior officers or the party line. Officers are punished or dismissed for disobeying senior officers, thus ending their careers and livelihoods. In disciplined parties, ordinary party members can be excluded for criticizing the party line, and elected deputies who vote against it may be expelled from the party and lose their seats. Such incentives are needed to maintain unity within groups.

Many armies and ruling parties lack this degree of internal discipline. In armies factionalized by ethnic, partisan, or personal loyalties, officers’ career prospects depend on their faction leaders’ success in achieving promotions and access to other opportunities. In such a military, lower-ranked officers cannot be counted on to obey the orders of higher-ranked officers from rival factions. In parties that have achieved dominance by persuading the leaders of other parties to “cross the aisle” in return for jobs and other spoils, discipline also tends to be low. A party history of incorporating most major political interests into one party tends to result in party factionalization based on ethnicity, region, policy position, or personal loyalties.

Where dictators have to bargain with an inner circle drawn from a unified and disciplined party or military, the threat of ouster is more credible and the price of support higher. Dictators in this situation face groups that, like labor unions, can drive harder bargains than the individuals in them could drive separately (Frantz and Ezrow 2011). In these circumstances, dictators usually find it expedient to consult with other officers or the party executive committee and distribute resources broadly within the support group. In short, the prior organization, unity, and discipline of seizure groups give dictators reason to maintain power-sharing arrangements with members of the inner circle.

If the original seizure group includes both a disciplined group and some additional allies, supporters affiliated with more disorganized groups pose weaker threats to the dictator and are thus less risky to exclude. As an example of this process, within months of the Sandinista rebels’ victory over the forces of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle in 1979, they had eliminated the democratic reformist (non-Sandinista) members of the broad coalition that supported the revolution (Gorman 1981, 138–42). Cold War observers noted that when broadly based coalitions that included a well-organized Marxist party ousted a government, the non-Marxist members of the coalition were shed soon after power was secured. The special perfidy of Marxist parties does not explain this phenomenon, however. It arises from the logic of the post-seizure situation. Military coup makers and well-organized non-Marxist parties also excluded their less unified and unneeded supporters once they had secured power. Non-Ba’thist officers from the intensely factionalized Iraqi military, for example, led the 1968 coup, supported by the Ba’th Party. To try to stabilize power sharing between these groups, the plotters chose a Ba’thist president (regime leader), and the non-Ba’thist coup leaders got prime minister, minister of defense, and command of the Republican Guard. Within less than two weeks, however, one of the non-Ba’thist coup leaders had been persuaded to join the party. The other non-Ba’thist coup leaders could then be excluded safely. They were forced into exile, leaving the Ba’th Party and its chosen leader able to consolidate a more narrowly based dictatorship (Tripp 2007, 184–85).

The dictator’s drive to narrow his support base arises from minimumsurvival coalition logic (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003). That is, the dictator wants enough support to survive in power, but no more because support must be paid for, even if at a low rate, in resources and shared power. The larger the number of individuals or groups over which resources must be spread, the less for each one. Because authoritarian governments need less support to remain in power after they have captured and transformed the state bureaucracy, courts, military, police, and taxing authority than for the initial seizure of power, they can get away with excluding some members of the seizure coalition and large parts of the population from the distribution of benefits.

The internal cohesion of seizure groups affects bargaining within the inner circle via two different paths. First, the dictator can bargain separately with each member of a factionalized seizure group, offering some special deals in return for siding with him on crucial decisions and inducing members of the inner circle to compete with each other for resources. If the dictator excludes a member of a factionalized inner circle, as Karimov did many times, remaining members are more likely to seize the resources of a fallen comrade and use him as a stepping-stone to a higher place in the hierarchy than rally to his support. Overall, members of factionalized seizure groups tend to get less from the dictator in exchange for their support because their competition with one another lowers the price they can extract.

Second, factionalism reduces the credibility of threats to oust the dictator if he fails to share. Factionalized support groups have difficulty organizing to oust the dictator, and most unarmed factions lack the capacity to oust him on their own. As we saw in the summary of recent Uzbek history at the beginning of the chapter, if one faction can credibly threaten the dictator with ouster, it can enforce its own sharing agreement, but most of the time unarmed factions cannot. Consequently, the dictator can concentrate more powers in his own hands.

In this section, we focused on one characteristic of seizure groups, which influences the credibility of threats by members of the dictatorial inner circle to oust the dictator: how much unity and discipline had been enforced within the seizure group before it seized power. When united militaries or disciplined parties lead authoritarian seizures of power, lieutenants are likely to be able to resist extreme concentration of power in the dictator’s hands. When, instead, factions divide the officer corps or parties are recent amalgams of multiple jostling cliques, they cannot obstruct the dictator’s drive to concentrate power. Our argument thus suggests an explanation for the personalization of power in many African countries noted by Africanists (e.g., Bratton and van de Walle 1997) after an initial seizure of power by the military or a transition from elected government to single-party rule. The newness of parties and the recent Africanization of the officer corps at the time of independence often resulted in factionalized party and military seizure groups in the first decades after independence.

Measuring personalism

In the next section, we test the argument about why dictators can concentrate power in their hands at the expense of their closest supporters. Though anecdotal evidence supports the ideas we propose, the absence of a measure of personalism has hampered our ability to evaluate them systematically in the past. Here, we leverage new data we collected on various features of dictatorship to derive such a measure.

To capture the idea of personalism, we use eight indicators of dictators’ observable behavior (assessed yearly) that we believe demonstrate power concentration at the expense of others in the dictatorial elite (Geddes, Wright, and Frantz 2017; Wright 2018). We create a time-varying index of personalism using these eight indicators: dictator’s personal control of the security apparatus, creation of loyalist paramilitary forces (create paramilitary), dictator’s control of the composition of the party executive committee, the party executive committee behaving as a rubber stamp, dictator’s personal control of appointments, dictator’s creation of a new party to support the regime, dictator’s control of military promotions, and dictator’s purges of officers.

The first two reflect the dictator’s relationship with security forces: whether he personally controls the internal security police (security apparatus) and whether he has created a paramilitary force outside the normal chain of military command (create paramilitary). Personal control of internal security agencies increases the dictator’s information advantage over other members of the dictatorial elite as well as his ability to use violence against them. The dictator’s advantage comes not only from his access to the information collected, which he can keep from other members of the inner circle, but also from his ability to order security officers to arrest his colleagues. Knowledge provided by security agencies can help the dictator identify members of the inner circle who might challenge him. Actions by the dictator that we code as indicating personal control of internal security include his direct appointment of the head of the security service (if this appointment appears to ignore the normal military hierarchy), his creation of a new security agency, and his appointment of a relative or close friend to lead a security force.

Dictators use paramilitary forces to counterbalance the regular military when they see it as unreliable. The creation of armed forces directly controlled by the dictator increases the concentration of power in that it reduces the regular military’s ability to threaten the dictator with ouster if he fails to share or consult. In order to identify only paramilitary forces created by dictators to solidify their personal power, we exclude party militias and those created to help fight insurgencies. We code both the appointment of a relative or close friend to command a paramilitary force and the recruitment of a paramilitary group primarily from the dictator’s tribe, home region, or clan as indicating his personal control. The forces coded as dictators’ paramilitary forces include Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana’s President’s Own Guard and Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guards.

The next indicator of personalism assesses the dictator’s relationship with the ruling party’s leadership. We code whether the regime leader chooses or vetoes members of the party executive committee (party executive) in dictatorships organized by a ruling party. The dictator has concentrated power, we argue, if he chooses top party leaders rather than party leaders choosing him. In communist Hungary, for example, the first dictator, Mátyás Rákosi, began the regime with a politburo composed of about equal numbers of close allies who had spent the war with him in Moscow and cadres who had spent the war underground or in jail in Hungary. Rákosi did not choose the leadership of the underground party members, meaning that he did not initially control the composition of the Politburo. After the seizure of power, however, Rákosi gradually eliminated those with independent bases of support in Hungary – life-long dedicated communists who were accused of treason, subjected to show trials, and sentenced to long prison sentences or execution (Kovrig 1984). By the early 1950s, Rákosi fully controlled who joined or was dismissed from the Politburo, and thus the Politburo could not constrain him.

A fourth variable also captures information about the ruling-party executive committee. It identifies party executive committees that serve as arenas for hammering out policy decisions rather than as rubber stamps for policy and personnel choices made by the dictator (rubber stamp). We see discussion of policy alternatives and disagreements over choices, which are reported in the media and in secondary sources, as indications that the dictator has not concentrated policy-making power. The absence of policy disagreements indicates the opposite. In North Korea, for example, Kim Il-sung reorganized the Korean Workers’ Party (KWP) leadership structure at the 1966 Party Congress; by 1968 “he faced no further challenges from within KWP” (Buzo 1999, 34). The party leadership had been transformed into a rubber stamp.

The variable appointments assesses the dictator’s control over appointments to important offices in the government, military, and ruling party. To code this item, we rely on secondary literature such as this statement about Mobutu Sese Seko, dictator of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo:

State-party personnel are completely dependent on him for selection, appointment, and maintenance in power . . . Mobutu constantly rotates the membership of the highest organs of power. (Callaghy 1984, 180)

The variable new party identifies country-years in which autocracies organize new ruling parties. We consider the dictator’s creation of a new support party a strategy for adding personal loyalists to the dictatorial inner circle. Bringing new members into the dictatorial elite dilutes the power of existing members (usually those who helped seize power) and increases the weight of the faction supporting the dictator. We code a new support party if the dictator or a close ally created a new party after the seizure of power or, in a few cases, during an election campaign before authoritarianization.14 When a dictator organizes a ruling party, he chooses its leadership. Such parties rarely develop sufficient autonomous power to constrain the dictator.

The last two indicators of personalism assess the dictator’s relationship with the military: whether he promotes officers loyal to himself or from his tribal, ethnic, partisan, or religious group (promotions) and whether he imprisons or kills officers from other groups without fair trials (purges). Dictator-controlled promotions and purges demonstrate the dictator’s capacity to change the command structure of the military, and thus the composition of military decision-making bodies. If the dictator can control the composition of the officer corps, the military cannot make credible threats to oust him if he fails to share power.

There is substantial overlap among these indicators, both because dictators who use one strategy for concentrating power in their own hands often use others as well and because one piece of historical information can sometimes be used to code more than one indicator. The information that Saddam Hussein appointed relatives to the military high command and to head the security apparatus and Republican Guard, for example, demonstrates that he controlled the internal security forces (security apparatus), personalized a paramilitary force (create paramilitary), and controlled military promotions (promotions).

Using these eight indicators, we create a composite measure of personalism from an item response theory (IRT) two-parameter logistic model (2PL) that allows each item (variable) to vary in its difficulty and discrimination. We transform the scores from this latent trait estimate into an index bounded by 0 and 1, where higher levels of personalism approach 1 and lower levels of personalism approach 0.

The personalism index differs from the categorical regime-type variables used in past research (e.g., Geddes 2003). The old measure classified differences across regimes (that is, spans of consecutive country-years), but the new one is coded every year in every regime to measure changes over time in the dictator’s concentration of power. Importantly, this time-varying measure is coded for all dictatorships – not just those with powerful leaders – to capture differences between regimes, between leaders in the same regime, and over time during any individual leader’s tenure in power. This allows us to investigate the gradual concentration of power by individual dictators (the most common pattern) as well as occasional reversals.

Figure 4.2 shows the personalism scores for six dictatorships: three communist dictatorships in Asia, all identified by Levitsky and Way (2013) as revolutionary regimes, and three coded as hybrid regimes by Geddes (2003) and not considered revolutionary. This latter group has features of personalist rule as well as features of military and party-based rule, which is the reason they were coded as hybrids of the three pure types. The personalism scores show how the concentration of power in the hands of paramount leaders varied over time in these long-lasting dictatorships.

In the left panel, we see that the personalism score for China (solid line) reflects the ups and downs in power concentration since the Chinese Communist Party took power in 1949. The highly collegial communist leadership immediately after the revolution was followed by the modest concentration of power in Mao’s hands during the 1950s, Mao’s loss of power after the failure of the Great Leap Forward, and then Mao’s rapid concentration of power in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution.16 The concentration of power dropped again as Mao’s health failed and normalcy was reestablished in the 1970s. Chinese leadership then became unusually collegial again except for a short time during Deng Xiaoping’s dominance. The North Korean regime (dashed line) was moderately personalist during its first years in existence under Soviet tutelage, but Kim Il-sung dramatically increased his control relative to other ruling party elites in the late 1950s and even more during the 1960s. His son and grandson maintained the extreme personalization of power in North Korea.

In contrast, Vietnam’s (hatched line) first dictator, Ho Chi Minh, never concentrated great power in his hands. The uptick of personalism in the late 1960s reflects the exclusion of the faction opposed to escalating the war in the south as Lê Duẩn consolidated his position as successor to Ho Chi Minh in the years before Ho’s death (Vu 2014, 28–30). The larger surge in personalism scores from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s reflects the post-war consolidation of power by Lê Duẩn and a handful of close supporters at the expense of other veteran communists. Lê Duẩn’s appointment of his son to head the secret police, appointment of other relatives to other important posts, and the purge of pro-Chinese factions from the party elite that enabled him to control promotions in the military demonstrate his concentration of power (Nguyen 1983, 70–72). The decline in Vietnamese personalism in 1986 coincides with Lê Duẩn’s death.

In the right panel, we note first that the early years of the dictatorships in Syria and Paraguay show a pattern similar to that in North Korea and China while Mao was alive: an initial period of relative collegiality followed by the rapid concentration of power in the dictator’s hands. This is the average pattern we find in the data. Note that in all three of these hybrid regimes, first dictators began their rule with more power than any of the communist leaders because none of them had to bargain with well-developed, unified party institutions.

Suharto of Indonesia (solid line) faced remarkably little constraint from other political elites even at the beginning. Not only did he lack a support party until creating one a few years after seizing power, but the upper ranks of the officer corps had been decimated by assassinations during a violent uprising not long before the coup that brought him to power. Consequently, Suharto did not have to negotiate with other highly ranked officers as most dictators from the military do. The precipitous drop in the personalism score for the last year of this dictatorship reflects Suharto’s resignation and his replacement by a weak protégé who lacked a support base in the military.

In Paraguay (dashed line) and Syria (hatched line), military dictators allied with preexisting but highly factionalized parties, which they reorganized, purged, and molded into effective instruments of personal rule over their first years in power. The Colorado Party in Paraguay was especially useful because, although hopelessly factionalized at the elite level and thus unable to exert much constraint on the dictator, it had a well-organized mass base that Stroessner coopted to use for both spying and mobilization against challenges from fellow officers. The steep drop in personalism followed by reconcentration in the 1980s reflects the development of competing factions within the Stroessner ruling group as he aged and members of the inner circle began to battle over succession. Stroessner briefly reasserted himself, but was then ousted by a member of his inner circle. The dramatic decline shortly before the regime ended reflects the tenure of this less powerful successor.

In these cases, the dictator who concentrated great personal power lived for several decades longer and maintained a high level of personalization, followed by a precipitous drop when he died, resigned, or was ousted. In Syria, we see a drop in personalization when Bashar al-Assad succeeded his father in 2000 and then an upswing as Bashar consolidated his hold on the system. In the other two, successors were unable to reconcentrate personal power or maintain the regime. In all cases, the personalism score seems to track historical events well.

Importantly, these time-varying indicators of personalism reflect observed behavior after the seizure of power. The indicators of factionalism within the seizure group that we employ below in the analysis to explain personalism reflect characteristics of what later became the seizure group measured prior to the seizure of power. They are thus not endogenously determined by dictators’ strategic behavior aimed at remaining in power.

Patterns of personalism

In this section, we use our measure of personalism to describe typical patterns of power concentration in dictatorships. Personalism scores tend to be low during the year after seizures of power, as would be expected if most dictators are weak, like Karimov, relative to other members of the ruling group when dictatorships begin. Where the dictator can take first steps toward power concentration soon after seizures of power, however, we expect him to then use his increased resources to eliminate from the inner circle individuals who have the greatest ability or disposition to challenge him in the future – as Karimov did. In this way, he can concentrate more power in his own hands. This strategy is associated with longer tenure in office for the dictator. First dictators – that is, those who are the first to assume power after the initiation of dictatorship – with higher personalism scores during their first three years in office retain their positions nearly twice as long on average as first dictators with low early personalism scores. First dictators with high personalism scores (top third of the personalism index) during the first years in power survive 14.7 years on average, while first leaders with low personalism scores (bottom third) survive only 7.8 years on average.19

Changes in the relative power of inner-circle members can become long lasting through the replacement of individuals who might potentially have challenged the dictator with others who lack independent support bases and are thus more dependent on him. Whatever resolution arises from the earliest conflict between the dictator and his closest allies increases the likelihood of a similar resolution to the next one. In other words, if the dictator gains more control over political resources as a result of the first conflict with other members of the inner circle, he then has a greater advantage in the next conflict with them.20 In this way, where steps toward personalization occur soon after the seizure of power, it is likely to progress further.

In contrast, initial reliance on collegial institutions reduces the chance of later personalization. Where members of the inner circle have developed the expectation of participating in key decisions, attempts by the dictator to reverse their policy choices or postpone regular meetings of the collegial decisionmaking body become focal points around which it is relatively easy (though never easy in absolute terms) to organize collective action against the dictator.

In short, we expect the deal agreed to by the dictator and members of the seizure group in the early months after the seizure of power to shape later interactions. Whatever pattern of power aggrandizement is established during the first years of a dictatorship tends to be perpetuated until the first dictator dies, sickens, or is overthrown.

The replacement of one dictator by another during a single regime often involves renegotiation of the distribution of power within the inner circle. Those who yearn to replace the dictator, whether after his death or via violent overthrow, must promise their colleagues a larger share of power in order to attract their support, but as with the first dictator, such promises are unenforceable unless members of the inner circle can both oust him if he reneges and credibly commit their subordinates to refrain from overthrowing him if he sticks to the bargain. The main differences between subsequent struggles and the first one is thatmembers of the inner circle have learned from earlier struggles andmay have developed disciplined, within-regime networks that allow them to bargain more credibly and effectively with the new dictator. In dictatorships that last beyond the tenure of the first leader, power relationships between the dictator and the inner circle thus tend to become somewhatmore equal under subsequent leaders.

We assess these expectations in two ways. First, we examine how levels of personalism change over time for a regime’s first leader relative to subsequent ones. The first dictator has an advantage in bargaining relative to later ones because of the inexperience of members of the ruling group. That is, they are experienced as military officers, insurgents, or party militants, but they have not usually had experience in the rule-free and dangerous context of bargainingwithin the inner circle of a dictatorship. The day after the new regime seizes power, the new dictator can begin using state resources, appointing officials, establishing procedures, and issuing decrees. It can take some time for other members of the inner circle to grasp all the implications of some of the dictator’s initiatives. This implies that, on average, first dictators have advantages over later ones in parlaying initial gains in personal power into further increases over time.

Figure 4.3 compares levels of personalism over time for initial regime leaders with the personalism scores of subsequent dictators in the same regime. The horizontal axis marks the first three full years each dictator rules, while the vertical axis shows the predicted level of personalism from a regression model in which the dependent variable is the measured level of personalism:

In this equation, Duration is the natural log of leader years in power; FirstLeader is a binary indicator of whether the dictator is the first one after the regime seizes power; γt are five-year time period effects; and i indexes leader and t indexes years in power. Time-period effects ensure that measurement error correlated with historical time is not driving the estimates of interest.

The figures below report the substantive effect of the linear combination of β2 and β3, which estimates levels of personalism for first regime leaders; and of β1, which estimates levels of personalism for subsequent leaders. By design, the approach simply shows the average levels of personalism as years in power increase, setting the average level in the first year as the baseline (set to zero on the vertical axis). The right panel of Figure 4.3 shows the result from a similar model specification but adds one crucial set of controls: an individual-level fixed effect for each dictator (δi). This allows the model to isolate the changes over time for each leader, net of any baseline differences between leaders in different countries or regimes.

The left panel shows the pooled data. During his first three years in office, the first regime leader, on average, increases the level of personalism nearly 0.15 points on the (0, 1) scale. For subsequent regime leaders, the gains in personalism are less than half of this. The right panel shows a similar pattern: the first leader increases personalism in the first three years by almost 0.09 points, while later leaders increase it by less than 0.02 points. The size of these effects is smaller in the right panel because the model accounts for all differences in the average level of personalism for each individual leader and thus looks only at each dictator’s time-trend in personalism. The descriptive patterns in Figure 4.3 are consistent with the expectation that first regime leaders have advantages in accumulating power. In the early years of dictatorship, the first dictator concentrates power faster than leaders who follow him.

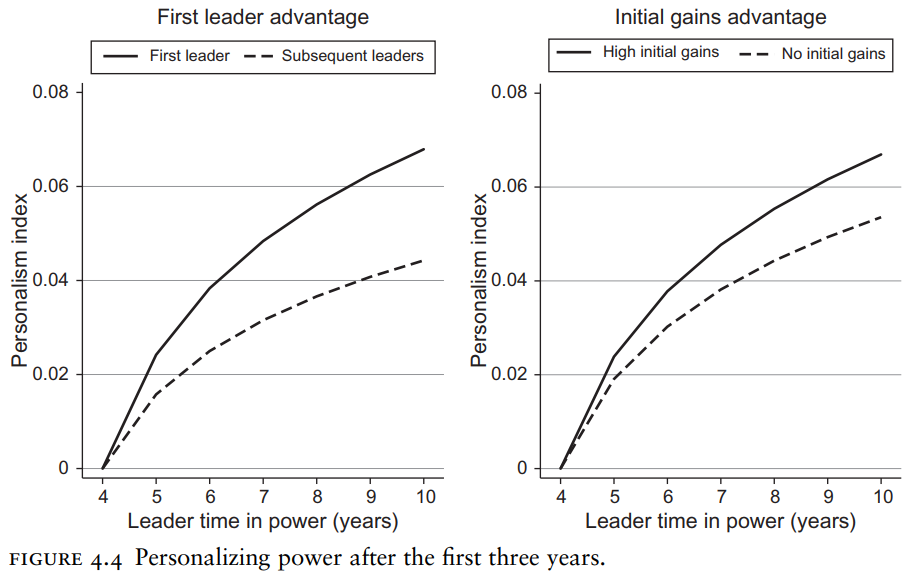

Next we examine what happens after an initial three-year period of regime consolidation. In this exercise, we look at how personalism evolves in years four to ten for different groups of dictators. Figure 4.4 shows the pattern of personalism across all dictators who survive in power at least four years, using the average level of personalism at the start of year four as the baseline level (set to zero). The left panel of Figure 4.4 reports the estimates for a model similar to Equation 4.1 but with leader fixed effects (like the right panel of Figure 4.3). After a period of initial power concentration, first leaders continue to have an advantage in accumulating power relative to subsequent leaders: first dictators, on average, boost personalism scores by a further 0.07 points between years four and ten, while subsequent leaders increase their power by half as much during these years. These increases are smaller than those reported in Figure 4.3 because power concentration is more rapid during initial periods of regime consolidation than during later years.

Another way to analyze personalization after the initial period of consolidation is to compare leaders who successfully personalized during the first three years with those who did not. For each leader, we construct a variable that measures whether his score on the personalism index increased a lot during the first three years he ruled (high initial gains). Then we test a regression model similar to those used above (with leader fixed effects), but compare leaders with high initial gains in personalism scores with leaders who did not concentrate power during their first three years. The right panel of Figure 4.4 shows that leaders who concentrate personal power in their first three years further increase their personalism scores by more than 0.06 points from years four to ten. Leaders who failed to accumulate personal power in their first three years do not make this up later; their gains after the initial period are smaller than those of leaders who amassed personal power from the outset. This evidence is consistent with Svolik’s (2012) model of power concentration in which initial successful power grabs beget more successful power concentration over time.

The effect of factionalism on the personalization of power

Next we test our explanation of why some dictators can concentrate more power than others. We look at the effect of the degree of factionalism in the seizure group before the initiation of dictatorship on how personalism evolves over time after the group takes power. We expect more unified seizure groups to bargain more successfully, and thus to limit the accumulation of power in the dictator’s hands.

Though we lack direct measures of seizure-group unity, we investigate the effects of two proxy measures. The first is the pre-seizure history of the group that becomes the dictatorship’s ruling party after the seizure. We posit that a support coalition organized as a political party either to contest elections or to lead a revolution before the seizure of power has greater organizational unity, and can thus more successfully bargain with the dictator, than a support coalition not organized as a party before the seizure.

The second proxy for coalition unity is intended to capture the pre-seizure unity of military seizure groups. For dictatorships that seized power in coups, we use the first dictator’s military rank before the seizure of power as a proxy measure of factionalism. The logic is as follows. Junior and mid-level officers carry out many coups. In countries with relatively unified and disciplined military forces, however, lower-ranked coup leaders hand regime leadership to a senior officer after the coup because they do not expect other senior officers to follow orders issued by junior officers. In factionalized armies, however, multiple hierarchies exist, some of which junior officers lead. When senior officers lead dictatorships, we cannot be sure whether the military that backs them is unified, but when junior officers such as Captain Moammar Qaddafi of Libya or Sargent Samuel Doe of Liberia lead dictatorships, we know that the military that backs them was factionalized before the coup. The indicator we use here groups regime leaders ranked major and below in one category and all those ranked higher in the other. It thus distinguishes the most factionalized cases (only the top 9 percent) from all others.

Seizure of power via popular uprising is another indicator of a factionalized army. Because popular uprisings are defined as unarmed seizures of power, they occur only when the country’s military has refrained from using its advantage in violence to quell the upheaval. When the army is united, either it backs the incumbent to prevent popular demonstrations from ousting him or it replaces the incumbent itself. The overthrow of a government by popular uprising suggests an army divided between government supporters and opponents just before the regime change, and possibly along other dimensions as well.