고정 헤더 영역

상세 컨텐츠

본문

Adam McCauley & Andrea Ruggeri

Regardless of perspective, philosophy, approach or assumptions, strong projects require a good research question. The process can be laborious, and the researcher will likely spend significant time in draft, making the question clear and explicit before it emerges in its polished form in the research project. For this reason and those outlined below, a scholar will face many of the core issues discussed in this chapter and its companion Chapter 1. For the lucky ones, the chapters on different methods will be eye-openers – whether on case studies and process tracing (see Chapters 59 and 62), formal theory (see Chapters 3 and 11) or the exploration of estimators in multivariate statistics (Chapters 33–57). However, each of these journeys begins with a singular prompt: what are you going to study?

This is the vital query of academic life. Any researcher, reviewer or dissertation committee member will wonder the following: what main question is this research aiming to answer? What is the relevance of the inquiry? What contribution will the potential answers make to the wider field? How conclusive can the answer be? The first three interrogations help scholars generate crucial research questions and phrase them most cogently. The final interrogation urges scholars to consider whether their questions are likely to lead to neat or complete answers. Potential indeterminacy should not dissuade the researcher, but should embolden her to explore and explain as much, as rigorously, as possible. Thus, this chapter explores how we can approach, imagine and generate research questions in international relations (IR) and how our answers can open pathways to related research projects. Our mission is to explore the craft of formulating research questions. Adopting the position of the craftsperson, beyond the idealized realm of the scientist, this chapter provides insights from published work and offers ‘rules of thumb’ to think systematically about the puzzles that motivate academic inquiry. We stop short of discussing different philosophies of social science and how they relate to the discipline, as there are excellent works on the epistemology of IR (Hollis and Smith, 1990; Fearon and Wendt, 2002; Jackson, 2016). Further, while we do not aim to dismiss other styles of research in IR, space limitations have forced us to be selective, and we have settled on the styles with which we are most familiar.

Where Research Questions Might Come From

While the research question is a prerequisite for any academic project, for all the time spent on methodological training, theoretical instruction and historical exploration in our field, we devote few formal resources to teaching the art of question development. In handbooks and courses on research design, ‘there is rarely any mention […] of the specific challenges students face when devising a research question’ (Bachner, 2012: 2).

Some ideas seem to emerge at random or through communing with colleagues in one's field. Often, though, questions emerge as the net results of unseen processes of thought – a mind's work tying together different ideas (old and new). These ideas then inform research questions, which, like their subsequent answers, become a product of continual evolution. Scholars can find it difficult to explain the origins of their interests in topics such as sanctions, international organizations, military occupation or civil wars. Even if the origins of their interest remain unknown, we argue that the practice of question formation can be looked at systematically, and pay careful attention to how we refine, specify and clarify research questions. Insights emerge from the working (and reworking) of one's inquiries and, as Bertrand Russell (2009) put it, ‘I do not pretend to start with precise questions. I do not think you can start with anything precise. You have to achieve such precision as you can, as you go along.’ This intellectual journey is as important as the destination.

To this end, patience and commitment are vital for the generation of knowledge. Scott Berkun challenges the very notion of an ‘epiphany’ – a word which suggests that inspiration comes from supernatural forces or beings – and suggests ideas emerge from a lifetime of hard work and personal sacrifice. What might at first glance appear to be driven by intuition or creative accomplishment is most often the result of systematic commitment to scholarly review. In this way, real innovation emerges from ‘an infinite number of previous, smaller ideas’ (Berkun, 2010) – it is not produced in splendid isolation. Alex Pentland (2014) illustrates the importance of social context for idea generation and finds intellectual strength in numbers, particularly when these crowds involve free-flowing ideas and a community engaged in the process of knowledge generation. These characteristics are essential for innovative and productive societies – and these insights ought to hold for smaller epistemic communities as well.

Steven Johnson (2011) agrees: ‘World-changing ideas generally evolve over time – slow hunches that develop, opposed to sudden breakthroughs.’ He argues that ideas may be aided by our better, stronger communication platforms, which allow us access to real-time information in ways never previously thought possible. Our age of communication also facilitates connections between researchers – and these networks retain intellectual weight to be leveraged in search of evocative questions. Through studying the complexities of innovation, Johnson highlights the importance of collaboration while stressing the value of preparation. Scholars must ‘do the work’ if they want to be in position for good fortune to strike. Finally, Johnson knows the route to understanding is not carved by successes alone, but by the failures that lead to mid-range solutions, and often to refashioning something old to create something new.For our purposes, we find the ‘literature review’ serves as the tangible product of this systematic approach: it aids scholars in identifying extant claims in the literature and helps orient their question to explore where the potential cause and effect might be identified. By knowing as much as we can about what works and what does not, or how things are assumed to work and might not, we are better able to generate pressing and potentially catalyzing research questions.

Connecting previously under-appreciated insights, however, demands that a scholar engage deeply across the broad expanse of IR scholarship. These scholars should explore beyond their sub-field into political science more generally (Putnam, 1988), and beyond their discipline into cognate areas of sociology (Wendt, 1999), psychology (Levy, 1997a), the detailed accounts of history (Gunitsky, 2014; Levy, 1997b) and models born of the study of economics (Hafner-Burton et al., 2017). Scholars will also benefit from their appetites beyond traditional scholarship, looking to fiction, television and films to leverage these created worlds to their advantage. Each of these creative spaces can convey important insights or stimulate questions that one's discipline might not. With this background – and a notebook filled with potential topics – researchers will be quicker to identify unexplored perspectives. The novelty of these topics will also be readily ascertained through participation in conferences and targeted (subject-specific) workshops.

Burkus (2014) also argues that creativity emerges when an individual can connect different types of knowledge. In the academic context, this creativity emerges when researchers incorporate relevant knowledge in parallel (but perhaps under-connected) disciplines in new and novel ways. Further, scholars also benefit from working between different sub-fields within their discipline, where insights and research puzzles are often found. Returning to the practicality of accomplishing this, scholars should look to the literature review as a forum for this considered and engaged intellectual exploration.

To this end, there are important differences between using and writing literature reviews, and the best illustrate how critical this initial survey can be. We can break this down into two versions of the literature review. The private review is for the scholar's own use. This survey connects assumptions, inconsistencies and insights, while highlighting possibilities for improvement. The public review is for the consumers of the finished scholarly product. This explains and situates the research project within the discipline. The private review can (and often should) be partially sacrificed for the latter, where only the critically important items are cited. All too often, early career scholars want to signal their commitment by adding extra entries to these public literature reviews, failing to distinguish between the logics that underpin the exercise: the logic of exploration and the logic of explanation. The final literature review, which adopts the logic of explanation, should serve as a storefront display displaying only the essential and most compelling items: neither customers nor your readers should have to search through the storage room to find what they came for.

The literature review embodies our philosophy for idea generation. This initial stage often focuses on identifying potential puzzles, and these early queries must be analyzed, challenged and sharpened before they can be polished for use. This process of discovery, through systematic reading and questioning, does not preclude creativity or emotional investment. In fact, these features are assets, given ‘the role of curiosity, indignation, and passion in the selection and framing of research topics’ (Geddes, 2003: 27). It is possible to be systematic and analytic while being motivated by indignation and passion, but it takes practice (Blattman, 2012). All ideas benefit from intellectual clarity, and good ideas, specifically, are the product of intellectual clarity. These good ideas will only be stronger if their discovery is motivated by inspiring research questions.

To this end, that clarity begins with simplicity. Scholars should begin with the most basic and essential assumptions of how causes, effects and/or processes unfold, and construct their research queries in response. Consider this approach akin to Occam's razor: start from simple premises and proceed with the most basic explanation to build your initial theory. By removing all premises that are clearly incorrect, we are left with propositions that might plausibly capture elements of the answer. Simplicity distinguishes superior inquiries and research designs.

Specific and General Research Questions

Academics often face the hedgehog or fox dilemma (Berlin, 2013): do you want to know a lot about one thing (hedgehog) or a little about many things (fox)? Are you interested in why the Mau Mau rebellion emerged in Kenya between 1952 and 1960, or are you interested in how civil wars begin? These questions are related, and their relationship is important. While a scholar eager to explain why civil wars emerge might use the Mau Mau as a case of interest, a scholar focused only on the Mau Mau can generate lessons learned about this case alone. Solving the hedgehog and fox dilemma demands a scholar decide what questions she can answer, how comprehensive these answers can be and how she imagines her insights might apply to the wider universe of cases. Fundamentally, it requires that the researcher decide whether to privilege causal identification, which limits the questions she can ask, or whether to ask an unbounded question, while remaining cognizant of any methodologically imposed limits to the resulting answers.

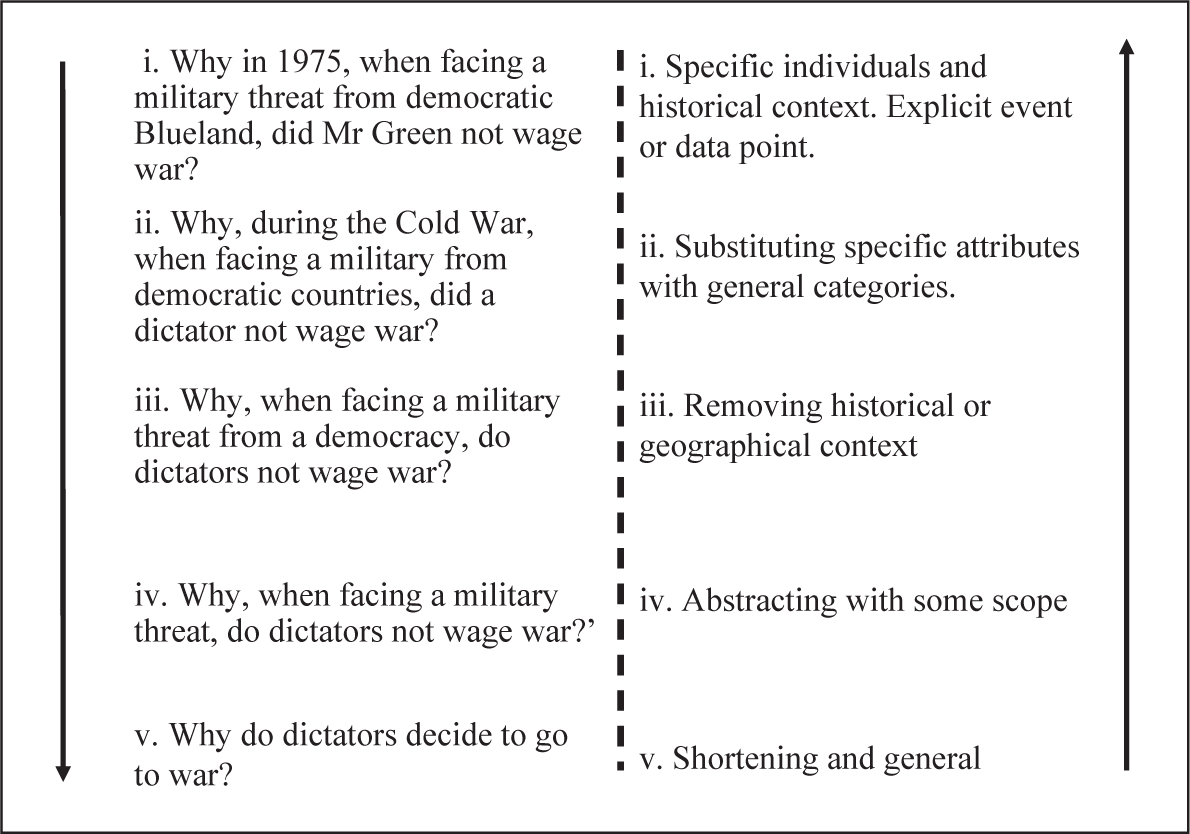

Figure 2.1 presents a schematic of the process of abstraction for a research question. Although most scholars use this process intuitively and implicitly, visualizing the practice can be pedagogically useful. This process mirrors the form of Sartori's (1970) ladder of abstraction and provides a step-wise sequence for a researcher to explore alternative levels of inquiry that may emerge within the research agenda.

Consider a fictitious dictator, Mr Green, who faced a military threat from a democratic country (‘Blueland’) in 1975 but decided not to wage war. The event is quite specific, as it focuses on only one person in a given year and within a single country. The second step calls for substituting the specific details of the case with more general categories. We replace Mr Green with the general term ‘dictator', change the specific date to a historical period (‘the Cold War’) and replace the country with the category of regimes to which it belongs (‘democratic countries’). Of course, this process assumes that these different conceptualizations are possible, and, further, that their operationalizations are plausible. These issues (conceptualization, operationalization and measurement) should not constrain the question-generating process but should be tackled directly in later stages of the project. The third step up the ladder of abstraction sheds the temporal and geographical dependence. Not all research questions are ahistorical or devoid of geographical context. In fact, as Figure 2.3 will make clearer, we believe quite the opposite: historical and geographical contexts have complex interaction effects (Eckstein, 1998; Tilly and Goodin, 2006). However, developing a research question demands an early attempt to simplify by eliminating layers of specificity,8 while recognizing that these layers can be added later when necessary. The fourth step focuses on the principal agent, the dictator, and drops the opposing regime type. In that way, we end up with a general research question and the project shifts from a study of interaction (dyadic type) that might explain war, to a study of a single regime type (monadic type) and its effects. This step retains some scope conditions by qualifying the circumstances that we are most interested in, namely, when the dictator is under a military threat. The final step reformulates the question so that instead of asking why something did not happen, we ask why it does. Although the puzzle was suggested by the absence of an event (i.e. the dictator did not go to war), posing the question in positive terms provides clarity, especially when there might be a complex set of causal paths that explain the absence of any phenomenon. This also echoes the preferred analytical posture of defining concepts in positive instead of negative and residual terms (Sartori, 1970). Thus, we settle on our final version: Why do dictators decide to go to war?10

Reading through case studies and historical accounts can be a useful starting point for exploring puzzles. Figure 2.1, viewed in reverse, illustrates a similarly valuable process of evolution, essentially ‘stepping down’ the ladder by adding specificity and context to the research question. This concentration of focus – shifting from the general to their specific elements – is a reflex of intellectual development and can be seen in many research agendas (see Figures 2.4 and 2.5 later in this chapter).

While ingenuity and originality are important for scholarly approach, all work lives within the ecosystem of extant scholarship. Researchers must not only motivate their specific question in the context of that scholarship but position their contribution among these existing studies. This means explaining how the findings clarify or qualify previous research; how their research remains relevant to the scholarly or policy communities; and – often overlooked – whether the aim of the project is feasible. One would do well to heed Merton's admonition from 1959 – still relevant today – that research agendas ought to: (1) focus on interesting and important phenomena in society; (2) lead to new studies of these social phenomena; (3) point to fruitful approaches for such studies; and (4) contribute to further development of the relevant research fields for these studies.

Research Question Pillars

There are four ‘pillars’ that are often discussed in terms of framing and motivating a research question: (1) a puzzle; (2) a gap; (3) a real world problem; and 4) feasibility (Figure 2.2). Research does not have to speak to all of these pillars, but it is important not to overlook an important fifth pillar: passion for the topic. This final pillar can mean the difference between success and failure.

| What's the puzzle? |

|

|

| Filling a gap? |

|

|

| Real-world problem? |

|

|

| Methodological rigor? |

|

|

| Will you enjoy it? |

|

|

Figure 2.2 Where good research questions come from

The Puzzle

Most inquiries begin with a compelling puzzle. As Zinnes (1980: 318) puts it, ‘puzzles are questions, but not every question is necessarily a puzzle'. Gustafsson and Hagström (2018) propose a formula that succinctly captures what research puzzles look like: ‘Why x despite y?', or ‘How did x become possible despite y?', where x and y are two variables that can be isolated and studied. A puzzle formulated in this fashion is, admittedly, a research question, but one requiring much closer familiarity with the state of the art than the basic ‘why-x question'. Importantly, you will only discover such a puzzle by exploring prior research. During this exploration, scholars should remain open to the unexpected: did you find conflict where you expected cooperation, or order when you expected disorder? Most puzzles present after reorganizing prior arguments and findings, when this review begins to highlight the logical tensions and empirical contradictions. This, alone, ought to encourage systematic reading of the literature to ‘connect the dots'.

A puzzle that is particularly timely can be additionally appealing. Many scholars have been able to start new research agendas on ‘hot topics’ in contemporary politics. These scholars might gain a ‘first mover’ advantage, but the potential benefits must be weighed against the risks of investing in a research agenda with little systematic prior work. In the early 2000s, the ‘new kids’ on the academic block were the pioneers of the latest generation of civil war study (Collier and Hoeffler, 2004; Fearon and Laitin, 2003). Subsequently, those ‘new kids’ were replaced by the disaggregation generation. Today, the first mover advantage may go to scholars studying cyber security and artificial intelligence.

Filling a Gap

As the second pillar in Figure 2.2 suggests, extant gaps in the literature present a clear starting point for new research projects. These gaps traditionally emerge at the weak points in previous theoretical frameworks or empirical designs. Researchers will benefit from challenging the assumptions that define either the piece of research or the related research agenda. For instance, this might include questioning how actors form preferences (Moravcsik, 1997) or whether actors adopt outcome-oriented rationality or process-oriented rationality (Hirschman, 1982). Perhaps extant research has focused too much on material incentives (capabilities, monetary aspects, etc.) and missed important dynamics associated with ideational aspects such as norms, ideas or emotions (Sanín and Wood, 2014; Checkel, 1998; Petersen, 2002). Perhaps there are stubborn, and under-analyzed, assumptions about the utility of specific strategies for a given outcome – e.g. that violence or force is an effective means of driving change. By challenging these assumption, scholars have developed pathbreaking work on the importance and influence of non-violent protest and its influence on regime change (Chenoweth and Stephan, 2011).

Challenging assumptions has a long history of sparking new research agendas in IR: where does action take place (Singer, 1961)? Where is the agency (Wendt, 1987)? Waltz (1959) wrote one of the core IR texts focusing mostly on this issue, asking: at what level should we analyze international politics – at the level of the individual, the subnational/local, the state/regime or international structure? Therefore, when we think about research questions and aim to formulate new research agendas, it can help to identify whether the phenomenon can be scrutinized either at the micro level (i.e. individuals), at the macro level (i.e. structural features) or as an interaction between both. Increasingly, scholars have identified the value of an intermediate layer, called the meso level, where different organizational configurations (an identity group, the state and international organization) can connect both the micro and macro levels of analysis.

Real-World Problems

Enterprising research often aims to respond to ‘real-world problems'. In part, this speaks to the utility of the intellectual practice: ‘Our task is to probe the deeper sources of action in world politics, and to speak truth to power – insofar as we can discern what the truth is’ (Keohane, 2009: 708). Karl Deutsch (1970), when discussing a new edition of Quincey Wright's A Study of War, wrote: ‘War must be abolished, but to be abolished must be studied.’ Pathbreaking research on security and strategy by Schelling (1960) clearly engaged with the issues in his contemporary period. The researcher ought to ask whether their research question has consequences for wider society and what (or whom) might be influenced by their findings. Another way to orient our thinking is to explore whether, and what kind, of non-academic may find value in the work. For non-academics, the incentive structure of publications and tenure-track preparation are replaced by a more tangible perspective of the work's value in terms of policy implications, implementation strategies, effectiveness and efficiency. These non-academics may be government analysts, politicians, practitioners employed by NGOs or civil servants at major inter-governmental bodies. These considerations ought to inspire scholars to avoid the crutch of academic jargon and to shy away from focusing on niche issues with unclear implications. In addition to crafting strong questions around specific themes or topics, researchers should strive for clarity in thought and communication. Empirical sophistication is no excuse for sloppy, senselessly convoluted style. Researchers would be well served to invest energy in crafting clear and ‘economical’ prose (McCloskey, 1985).

Despite perennial and contentious debates over the discordant responsibilities of the professional academic and the policy maker, students of IR have learned a few lessons. First, if authors are clear about possible policy implications, those policy makers will be more apt to read and incorporate their research. Second, clarity of argument and assertions should be considered a duty, particularly if your research resonates with contemporary policy challenges. If the policy implications are not made explicit, policy makers are likely to infer their own conclusions, potentially misusing the research. One debate around the 2003 invasion of Iraq focused on the Bush administration's misuse of the democratic peace literature in legitimizing the military intervention (Ish-Shalom, 2008). This point speaks to our question in Figure 2.2: what are the ethical implications of study? Researchers should be honest and self-reflective about potential challenges when it comes to the methodological approach and the practice of gathering evidence. Further, they should reflect on the effect of publishing publicly on findings with clear social costs: it is incumbent on the researcher to fully understand the consequences of their work, for themselves and everyone they have involved. Academic institutions have strict procedures and processes to assure that people who participate in a research project will not be facing any risks. Supervisors and senior colleagues should assist and advise early career scholars given the intrinsic dangers of studying certain phenomena in international relations.

Feasibility

This pillar represents an important concern in political science and IR. Our first question is trenchant, though problematic: will you have the necessary data and methods to find an answer to your new research puzzle? This question is a necessary first inquiry, as it may also be the last: supervisors and more experienced scholars are always concerned with the feasibility of the project and might try to refocus the core question if the answer demands resources and skills beyond what is currently available. It is possible that these individuals are wrong – perhaps they are not creative or visionary enough to see the potential – but one ignores this concern at one's own peril. It is difficult to know early in the process what methods and data will be most useful, and whether they will be available. Effective review of methods and existing data is a critical step (and one with which this Handbook is designed to assist). Scholars should find out whether the requisite data exist, but not despair immediately if the answer is unclear. A range of successful research projects involve data collection, sometimes exclusively so (Singer and Small, 1994; Sarkees and Schafer, 2000; Vogt et al., 2015; Sundberg and Melander, 2013; Tierney et al., 2011). However, one should be careful, as large data collection is quite demanding and expensive – most of the existing datasets are the product of years of research and were obtained by small armies of coders or through use of advanced automated data gathering tools. PhD students and early career scholars could face serious challenges if the data collection is not constructed carefully. Pragmatism is an asset in assessing the realities of obtaining the necessary data.

Enjoying Your Research

Undertaking a research project comes with associated opportunity costs – time, energy and interest expended on any research project are resources a scholar cannot use elsewhere. Thus, it may matter whether the research project is strictly one of your choosing or one suggested (or even imposed) by someone else. Suggested topics may, at times, come from a supervisor or academic peers, and a particular approach may be imposed according to the availability of data. You may also have stumbled into your research question through previous study or thanks to an essay or assignment you have already written. You need to ask yourself: does the topic continue to inspire you? Do you enjoy working on it?

In the end, a research project is 10 percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration, and while a creative mind is an asset, the eventual result will depend on your commitment, hard work and effective time management. Further, scholars should also be aware that starting a completely new or novel research agenda is comparatively rare in an academic life – and perhaps a luxury, as well. However, understanding your personal interest and stakes in a project is important for deriving joy from your work and will be helpful in motivating scholars to finish their projects.

Developing Research Questions

We now consider a range of possible research questions, as shown in Figure 2.3. This list is not exhaustive, but it does provide a starting point for crafting them. Broadly speaking, there are two types of research question. The first focuses on the main phenomenon to be explained (Y, the dependent variable, or explanandum). The second focuses on factors that can explain variations in that Y (X, the independent variables, or explanans). Both types are legitimate queries for research, although they might involve different methods and approaches.

The first ideal type – ‘what is Y?’ – is the most direct of the explanandum-oriented research questions. This question is highly theoretical, involves heavy conceptualization and is likely to produce typologies that might be useful for follow-up questions (Collier et al., 2012; Gerring, 1999). ‘What is Y’ queries also demand data to describe different trends and types (Gerring, 2012). Although we use ‘power’ as our example, we could easily have picked something else from a wide range of similar forms of inquiry in IR: security (Baldwin, 1997), human security (Paris, 2001), securitization (Buzan, 2008), or civil war (Sambanis, 2004; Kalyvas, 2005).

The second ideal type remains focused on Y, but instead of seeking to provide a conceptual definition, it tracks how Y has changed over time and space. Research agendas such as those charting countries’ Polity IV scores (Marshall and Jaggers, 2002) or calculating their position on the V-Dem spectrum (Coppedge et al., 2017) belong to this family of research questions.

The third type also starts with a definition of Y, but proceeds to provide potential explanations of the data-generating process while maintaining that definition. These questions are very useful for elaborating and studying mechanisms (Tilly, 2001; Hedström and Ylikoski, 2010). One of the most cited articles on processes leading to war, ‘Rationalist Explanations for War’ (Fearon, 1995), belongs to this style of research. What is an appropriate way to define war? What can account for the occurrence of war thus defined? The conceptual framing of the question and the provision of several tentative mechanisms that could answer the puzzle posed by the definition have made this article foundational in the study of war.

The fourth type is the natural extension of the third and involves starting with the classic phrase ‘under what conditions…'. This framing is useful because it pushes the researcher to think about variations of Y, their central variable of study, as well as the influence owing to variation of possible explanatory factors – the Xs. Hence, under what conditions suggests we should be conscious of co-variation.

The next three types of question seek to make this co-variation more explicit. Here, the choice of adjective or verb suggests the nature of that correlation. Specifically, in Figure 2.3 question type six outlines the causes of effects, while question seven refers to the effects of causes. This distinction is easy to state, but harder to distinguish in practice. Effects may have multiple causes and these causes inevitably give rise to a range of effects. Situating your research within this space is important and should be done consciously. Moreover, these ideal types are particularly important for our contemporary study of IR, and have attracted the attention of contemporary scholars (Van Evera, 1997; Samii, 2016; Lebow, 2014). Researchers should be cautioned against slipping into unfounded causal claims, however. Are democracies richer? Do democracies fight each other less than they fight other regime types? Do countries that are members in many IOs trade more than countries with fewer memberships?

For this, one could ask directly: does X cause Y? It used to be that quantitative scholars were less concerned about the differences between correlational and causal claims. Many incorrectly assumed that endogenous effects (those that emerge within the phenomenon of study) could be suitably controlled by lagging (modulating the expected influence) the relevant variables, and that omitted causal effects could be discerned by imposing specific scope controls. The emergent consensus about the importance of causal identification has changed all that (Angrist and Pischke, 2008; Samii, 2016). Projects that had employed apparently solid quantitative causal identification strategies can now be challenged with qualitative and archival information that casts doubt on the supposed exogenous identification (Kocher and Monteiro, 2016). Qualitative scholars are also increasingly aware of the high bar for causality, which has led to the development of sophisticated approaches to methods such as process-tracing (Bennett and Checkel, 2014).

The last three ideal types of questions add layers of complexity. They ask whether the effect of X on an outcome is conditional on, or mitigated by, another factor Z. These queries tend to make research agendas more dynamic and expansive since they push researchers beyond studying X and Y alone. This can involve theoretical and methodological improvements. For example, quantitative scholars have been developing better ways of studying interactions between variables (Brambor et al., 2006; Franzese and Kam, 2009), while qualitative scholars have provided systematic approaches to conditionality and contextuality (Tilly and Goodin, 2006). The additional factors might also involve time (different historical periods or temporal moments) or space (regions or other appropriate geographical variables).

Examples from IR: Democratic Peace and Civil War

We now sketch some lessons learned by looking (briefly) at two research agendas in IR: democratic peace and civil war. Readers who are not specifically interested in the topic of security in IR could seek to draw parallels with other areas of IR or more broadly in Political Science.

| Figure 2.4 Stylized democratic peace research agenda |

|

Figure 2.4 sketches a (non-comprehensive) trajectory of research questions and topics about the democratic peace. This is one of the final IR debates in which paradigms remain in contention.

The research agenda began with a broad research question, with subsequent studies providing more stringent scope conditions and improved accuracy of empirical analysis. Subsequent debates have centered on how to make sense of the correlational findings: if democracies do not fight each other, we need mechanisms to explain why this might be the case (Maoz and Russett, 1993). In response, several papers, mostly from a realist perspective, challenged the pattern of causation and the conceptualization, while hinting toward possible omitted variable bias (Rosato, 2003). Given the rarity of the phenomenon (not just war, which is already rare, but war that involves democracies on opposite sides, which should be even rarer, as the central assertion in this literature would have it), critics argue that it is difficult, and perhaps foolhardy, to make inferences from such a small sample. In response, scholars offered more elaborate explanations, finding cause for the seemingly pacific relations between democracies in variables such as trade or international organizations (Oneal and Russett, 1999; Russett and Oneal, 2001).

Subsequent developments adopted non-realist perspectives, and either attempted to shift the focus to variables other than regime type (e.g. capitalism (Gartzke, 2007), although see Dafoe (2011) for a methodological critique), or to dig deeper into the microfoundations of the proposed mechanisms (Tomz and Weeks, 2013).

Figure 2.5 offers a schematic of how research on civil wars has evolved. The study of civil wars has an established research pedigree but it experienced something of a renaissance in the 2000s (Kalyvas, 2010), as research became more systematic and publications more abundant (Fearon and Laitin, 2003; Collier and Hoeffler, 2004).

| Figure 2.5 Stylized civil war research agenda |

|

This period of academic exploration offered a range of arguments about the variables related to the onset of civil wars, moving beyond the traditional economic or ethnic factors. Many studies sought to explain the variation in civil wars with capabilities (of host states and non-state actors), countries’ exports, domestic shares of natural resources and demographic patterns, among others. Scholars unpacked different facets of civil wars by looking carefully at their duration, intensity and level of violence against civilians (Kalyvas, 2006). Some proposed different levels of analysis to match the theoretical concepts and empirical operationalizations (Cederman and Gleditsch, 2009). This work has benefited from intensive data-collection exercises about the actors involved (Cunningham et al., 2009), the transnational linkages between these actors (Gleditsch, 2007), other relevant local features (Sundberg and Melander, 2013) and leader attributes (Prorok, 2016). Qualitative work has not lagged behind, either, with research on rebel governance (Arjona, 2016), systems of alliances (Christia, 2012), and their splintering and their influence on displacement (Steele, 2009). More recently, scholars have started to explore how the processes leading to political violence might be related. We now have studies of the substitution effects between civil wars and terrorism (Polo and Gleditsch, 2016), and between civil war and military coups (Roessler, 2016). The field of inquiry has also expanded to incorporate insights from the study of organized and transnational crime (Kalyvas, 2015; Lessing, 2017).

As both our brief examples illustrate, research agendas progress through systematic refinement. Scholars challenge each other's intuitions, assumptions and findings, and – in the process – reassess the models and methods being employed. Progress is built on failure, but it is failure forward, toward better understanding. The initial conceptual thought about the nature of a phenomenon (‘what is security?’) provides a center of gravity that attracts subsequent research that unpacks the latent assumptions, alters the levels of analysis, and critically engages the conclusions reached. These improvements often come from leveraging new methods or specifying new mechanisms that connect the variables. These interventions often offer competing explanations of empirical patterns, which, in turn, pique the interest of new generations of scholars who jump in to analyze under-explored or emergent puzzles associated with these phenomena.

Conclusion

Can you pass the ‘elevator test'? That is, can you succinctly explain your research question and project aims in less than 45 seconds? The time limit is arbitrary, but the question helps sharpen the clarity of your work. If you cannot pose a short coherent question and provide the gist of the answer, then there is something amiss with your project. One often achieves this clarity after repeatedly writing and rewriting one's ideas until they are thoroughly understood. You cannot effectively communicate things you only dimly understand. All acquisition of knowledge relies on commitment, iteration and a significant amount of writing, thinking, and writing again. ‘You do not learn the details of an argument until writing it up in detail, and in writing up the details you will often uncover a flaw in the fundamentals’ (McCloskey, 1985: 189).

Clear communication is crucial because journal editors and book publishers ask reviewers to assess where a project fits between four categories: a relevant contribution to a relevant topic; an irrelevant contribution to a relevant topic; a relevant contribution to an irrelevant topic; or an irrelevant contribution to an irrelevant topic. While it is usually easy to avoid falling into the last category, careless write-ups and hidden flaws in the research process can often strand submissions in the second and third categories. Depending on the patience of referees, this might also lead to outright rejection. Always be conscious of how to position yourself in that first category.

Thus, research projects are not simply assessed in terms of good or bad. They can be good or bad across a set of characteristics – from analytical rigor to methodological appropriateness – and should be evaluated across multiple dimensions. 15 It is also important to ask whether research can be ‘creative and inspiring in a swashbuckling way', as scoring high on this dimension often signals that the research agenda can make a substantive difference. Of course, being rigorous and innovative is great, but every researcher should strive for intellectual humility, remaining cognizant of the potential costs and risks involved.

We conclude our chapter with a brief ‘Questions & Answers’ section that might be instructive to readers.

How Specific Should a Research Question Be?

From ‘why do civil wars start?’ to ‘why did the Mau Mau rebel against British rule?', there are varying degrees of generality. However, as we emphasized in our discussion, scholars can ask general questions and explore them through specific cases or start with specific cases and build toward more general abstractions. The answer depends on what scope conditions you select and how generalizable you wish to be. There are tradeoffs on either end of this spectrum.

Shall I Only Select Questions I Can Fully Answer?

This is an important question and there might be disagreements about the answer. When discussing Figure 2.2, we stressed the tradeoff between originality and feasibility. However, we also suggested that there are myriad ways of assessing the potential and value of research agendas. Our advice is to be more curious than concerned in the exploratory phase, while rationally assessing the feasibility before you commit to the project over the longer period. Creativity and innovation are important features of any research project.

How Useful Is a Literature Review When Posing a Research Question?

Researchers with a thorough knowledge of previous research (in content and method) will have a demonstrable advantage over those without. Remember the distinction between a logic of exploration and a logic of explanation when writing literature reviews. The former is crucial for posing a proper research question; the latter is vital when writing in a piece of research and situating its contribution and relevance.

Do I Need to Justify My Research Question?

Researchers must do more than justify their topic – they need to situate their research questions. What previous research are you engaging with or challenging? What research streams does your project bring together? What is your intended contribution (what will we learn within IR or Political Science?) and how is it relevant (why should we care?)

What Do I Need to Define in My Research Question?

Definitions are central for research, but their importance varies with the type of research question that you are engaging with. If your question is a Y-focus query, most of the research will be about conceptualization, defining ideal-types and discussing typologies. X-focused research questions will also require clear definitions, but this will likely occur at a later stage in the research design.

How Many Research Questions?

A good rule for any piece or writing or research is one paragraph, one idea. Applied to research, a reasonable rule of thumb might be one dominant research question for each paper, where a book or thesis might have more – though usually these questions are closely related. This predominantly takes the form of a large research question with different, but reinforcing, sub-questions that can improve the comprehensiveness of the project. Remember, the more research questions you pose, the harder it will be to answer them. Less is more, particularly if those questions are comprehensively studied and answered.

Do I Need to Keep the Same Dependent Variable?

Usually, yes. Switching among things you are trying to explain can be disorienting for a reader unless your central argument is about a selection process (Z → X, then X → Y) or a recursive one (X ↔ Y). Moreover, when you are formulating hypotheses, it is good practice to keep the Y consistent. Consistency improves project clarity.

Do I Need Only One Main Explanatory Variable?

Not necessarily. International relations, and politics in general, are complex, and several factors are often necessary to account for the variation of IR phenomena. However, scholars often mix main explanatory factors (what should be the core contributions of the research project) with controls (other factors that could be affecting the dependent variable). This is especially prone to happen in the early stages of the research projects. Not all Xs should be placed under the spotlight. Focus on those Xs that make a contribution and remain essential to your research question.

Can I Change My Research Question?

There are two ways to interpret this question: as a change of topic, or as a change of the specific question being asked. The former is beyond our scope, as it comes down to the individual researcher or to their relationship with the supervisor or PhD advisor. The latter, however, may simply happen as you read more of the literature, strengthen your theoretical argument and advance your empirical analysis. Not all change is bad, but be conscious of why you are doing it.

Do I Need to Specify Actors, Preferences, Strategies and Other Relevant Components of My Theory in the Research Question?

Not necessarily, but they can assist in formulating the research question and project directives. Understanding at which level the analysis is being conducted, where agency is located, what preferences are involved and how they are formed can be crucial. These details help us explain the strategies actors adopt and help identify the structural constraints and ideational factors that might influence them. This information is essential for theorizing and can help refine your research question.

When Should I Ignore Your Advice?

We, like everyone else, are limited by our own subjectivity. In any domain where creativity is central and where the routes to knowledge are many and varied (and sometimes deeply personal), there is a risk of dissuading researchers from following their own intuition and insights. We have tried to be systematic and egalitarian in our treatment of differences, but we cannot possibly account for all situations. We hope that our advice highlights common issues and potential solutions, so take our advice as formative, not conclusive.

'Quantitative Study' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 5. The Humanities (0) | 2023.04.07 |

|---|---|

| 8. Critiques, Responses, and Trade-Offs: Drawing Together the Debate (0) | 2023.03.28 |

| 7. The Importance of Research Design (0) | 2023.03.28 |

| 6. Bridging the Quantitative-Qualitative Divide (0) | 2023.03.28 |

| Chapter1 : Asking Interesting Questions (0) | 2023.02.23 |