고정 헤더 영역

상세 컨텐츠

본문 제목

Popular Support for Democracy (1. Introduction Comparative Perspectives on Democratic Legitimacy in East Asia)

본문

One of the central tasks of the EAB survey was to measure the extent to which East Asian democracies have achieved broad and deep legitimation, such that all significant political actors, at both the elite and mass levels, believe that the democratic regime is the most desirable and suitable for their society and better than any other realistic alternative. We employed a set of five questions to estimate the level of support for democracy. These questions address democracy’s desirability, suitability, efficacy, preferability, and priority.

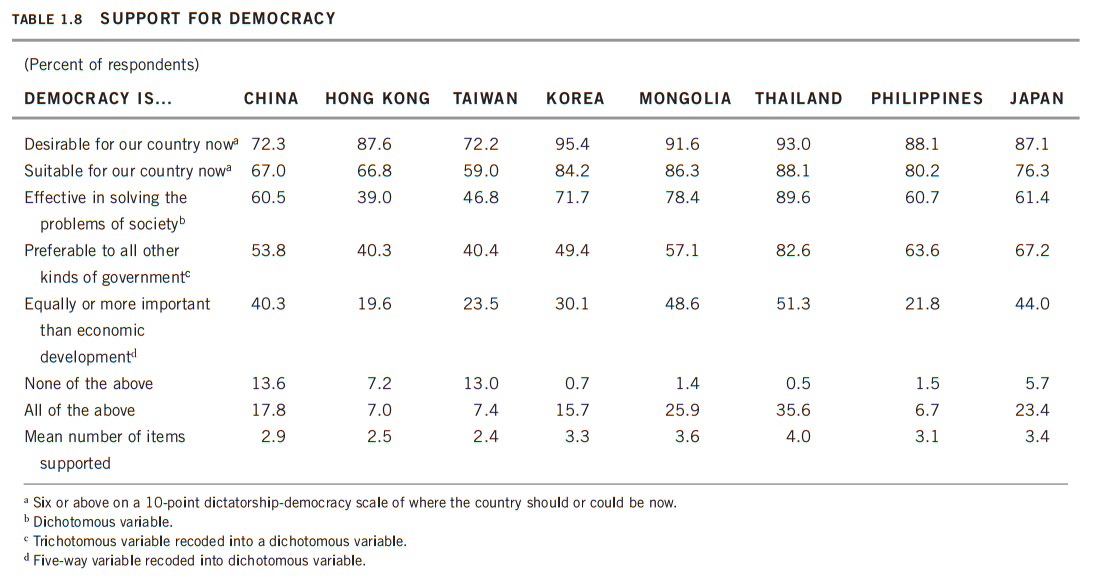

We measure the “desirability” dimension by asking respondents to indicate on a 10-point scale how democratic they want their society to be, with 1 being “complete dictatorship” and 10 being “complete democracy.” The first row of percentages in table 1.8 shows that in most societies, except China and Taiwan, overwhelming majorities (87% or higher) expressed a desire for democracy by choosing a score of 6 or above. In Taiwan, 72.2% of the electorate expressed their desire for democracy, which is not a very impressive ratio in comparison with South Koreans’ near unanimity (95.4%). On this score, Taiwan trails behind not only all East Asian democracies, but also Hong Kong.

Next, respondents were asked to rate the suitability of democracy for their society on a 10-point scale, 10 being perfectly suitable and 1 being completely unsuitable. The second row of table 1.8 indicates that in most East Asian societies at least 75% of respondents considered democracy suitable. The gap between the desirability and suitability measures suggests that there are many East Asians who in principle desire to live in a democracy, but who do not believe that their political system is ready for it. Taiwan again fares unimpressively on this measure, with only 59% of the respondents looking favorably on the suitability issue, trailing behind Hong Kong’s 66.8% and China’s 67%. It may not be coincidence that a sizable minority is skeptical about the suitability of democracy in all three culturally Chinese societies. This reflects the lingering influence of their common cultural values, which privilege order and harmony.

The EAB survey asked respondents whether they believed that “democracy is capable of solving the problems of our society.” East Asians hold divergent views on this efficacy question. When sampled in late 2001, Thais overwhelmingly (89.6%) believed that democracy is capable of addressing their problems, while only 39% of Hong Kong respondents answered the question in the affirmative. In most regimes, a majority expressed their belief in democracy’s efficacy for solving their societies’ problems. Nevertheless, across all eight of these cases, the proportion of people who registered their doubt about democracy’s problem-solving potential was substantially higher than those questioning democracy’s desirability or suitability. This suggests many East Asians attached themselves to democracy as an ideal, but not as a viable political system.

The EAB survey also included a widely used item for measuring popular support for democracy as a preferred political system. Respondents were asked to choose among three statements: “Democracy is always preferable to any other kind of government,” “Under some circumstances, an authoritarian government can be preferable to a democratic one,” and “For people like me, it does not matter whether we have a democratic or a nondemocratic regime.” It turns out that popular belief in the preferability of democracy is lower in East Asia than in other third-wave democracies. In Spain, Portugal, and Greece, more than three-quarters of the mass public say democracy is always preferable in survey after survey (Dalton 1999:69). In East Asia, only Thailand (82.6%) had reached that threshold. In Japan, only 67.2% of respondents said they always prefer democracy to other forms of government, lower than the average (above 70%) of the twelve sub-Saharan countries surveyed by Afrobarometer around 2000 (Bratton, Mattes, and Gyiman-Boadi 2005:73). In Taiwan and South Korea, more than half of those surveyed either supported a possible authoritarian option or showed indifference to the form of government, pushing the support level down to 40.4% and 49.4% respectively. Outside East Asia, such low levels of support are found only in some struggling Latin American democracies such as Ecuador (Latinobarómetro 2005). This low level of popular support in the two East Asian tigers in spite (or because) of their higher level of socioeconomic development underscores the point we have already made: in societies where people have experienced a variant of soft authoritarianism that was efficacious in delivering social stability and economic development, democracy will have a difficult time winning people’s hearts.

To measure the priority of democracy as a societal goal, the EAB survey asked, “If you had to choose between democracy and economic development, which would you say is more important?” Across the region, democracy lost to economic development by a wide margin. Only about one-third of Japanese respondents and slightly over a quarter of Mongolian respondents favored democracy over economic development, while fewer than one-fifth of respondents felt that way in Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, and the Philippines. On this score, East Asians and Latin Americans look very much alike, despite the fact that most East Asian countries have enjoyed an extended period of rapid economic expansion. According to the 2001 Latinobarómetro, 51% of Latin Americans believed that economic development was more important than democracy; 25% thought democracy was more important; and 18% stated that both are equally important. One possible reason for an overwhelming emphasis on the priority of economic development in East Asia is the psychological impact of the region’s financial crisis of 1997 and 1998. In the aftermath of this economic shock, most East Asian citizens no longer took sustained growth for granted. In China and Mongolia, the two countries that were relatively insulated from the financial meltdown, more people were willing to put democracy before economic development than elsewhere.

To summarize the overall level of attachment to democracy, we constructed a 6-point index ranging from 0 to 5 by counting the number of prodemocratic responses on the five items discussed above. On this 6-point index, Japan registered a high level of overall support with an average of 3.4, while Taiwan and Hong Kong registered the lowest, with 2.4 and 2.5 respectively. Across East Asia, few people gave unqualified support for democracy. Even in Japan, only around 19% of respondents reached the maximum score of 5. This suggests that East Asia’s democracies have yet to prove themselves in the eyes of many citizens.

Our findings make clear that normative commitment to democracy consists of many attitudinal dimensions and the strength of citizens’ attachment to democracy is context-dependent. The more abstract the context, the stronger the normative commitment; the more concrete the context, the weaker the commitment. The conclusion will develop this point further on the basis of the country chapters: citizens’ commitment to democracy responds sensitively to the democratic regime’s perceived performance—its ability to deliver political goods. Democracy as an abstract idea was widely embraced. But not so many people endorsed it as the preferred form of government under all circumstances, and few preferred it to economic development.