Electoral Institutions, Cleavage Structures, and the Number of Parties

Octavio Amorim Neto, University of California, San Diego

Gary W. Cox, University of California, San Diego

Theory: A classic question in political science concerns what determines the num ber of parties that compete in a given polity. Broadly speaking, there are two ap proaches to answering this question, one that emphasizes the role of electoral laws in structuring coalitional incentives, and another that emphasizes the importance of preexisting social cleavages. In this paper, we view the number of parties as a product of the interaction between these two forces, following Powell (1982) and Ordeshook and Shvetsova (1994).

Hypothesis: The effective number of parties in a polity should be a multiplicative rather than an additive function of the permissiveness of the electoral system and the heterogeneity of the society.

Methods: Multiple regression on cross-sectional aggregate electoral statistics. Un like previous studies, we (1) do not confine attention to developed democracies; (2) explicitly control for the influence of presidential elections, taking account of whether they are concurrent or nonconcurrent, and of the effective number of presi dential candidates; and (3) also control for the presence and operation of upper tiers in legislative elections.

Results: The hypothesis is confirmed, both as regards the number of legislative parties and the number of presidential parties.

The study of political parties and party systems is one of the largest subfields of political science. Within this subfield, a classic question con cerns what determines the number of parties that compete in a given polity. Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to answering this question, one that emphasizes the role of electoral laws in structuring coalitional incentives, and another that emphasizes the importance of preexisting social cleavages. The first approach-found in the work of such scholars as Duverger(1954), Sartori (1968, 1976), Rae (1971), Lijphart (1990, 1994), Riker (1982), Taagepera and Shugart (1989), Palfrey (1989), Myerson and Weber (1993), and Cox (1994)-can be exemplified by what Riker has dubbed Duverger's Law: the proposition that "the simple-majority single-ballot system [i.e., simple plurality rule in single-member districts] favors the two-party system" (Duverger 1954, 217). The logic behind this proposition looks both to the incentives that face voters under the plurality voting system (they will avoid wasting their votes on hopeless third party candidacies) and to the incentives that consequently face elites (they will avoid wasting their time, money, and effort in launching what the voters will perceive as hopeless candidacies, instead looking to form coalitions of sufficient size to, win a plurality).

The second approach-associated with the work of such scholars as Grumm (1958), Eckstein (1963), Meisel (1963), Lipson (1964), Lipset and Rokkan (1967), Rose and Urwin (1970)-can be exemplified by Lipset and Rokkan's famous freezing hypothesis: the proposition that the European party systems stabilized or "froze" in the 1920s, and continued with the same basic socially-defined patterns of political competition (and some times the same parties competing) until at least the 1960s. The logic behind this proposition relies on an implicit notion of social equilibrium to account for the longevity of the party systems spawned in early twentieth-century European industrial democracies.

The two approaches just sketched coexist uneasily. Some adherents of the sociological school question whether Duverger's generalizations serve "any useful function at all" (Jesse 1990, 62); argue that the institutionalists have got the direction of causality backwards;' or argue that the institution alists have simply focused on a relatively unimportant variable, at the ex pense of a relatively more important variable-the number and type of cleavages in society. Adherents of the institutionalist approach object to a belief that socially defined groups will always be able to organize in the political arena, because this ignores the problem of collective action (Olson 1965); or object to a belief that social groups will always organize as par ties, because this assumes that "going it alone" is always a better strategy than forging coalitions; or argue that politicians can take socially defined groups and combine or recombine them in many ways for political purposes(Schattschneider 1960)-so that a given set of social cleavages does not imply a unique set of politically activated cleavages, and hence does not imply a unique party system.

Despite these differences, however, the two approaches are not mutu ally exclusive. To assert that social structure matters to the formation and competition of parties-which no one denies, when the point is stated in such a broad fashion-does not imply that electoral structures do not mat ter. To make this latter point, one has to adopt a rather extreme monocausal ist perspective according to which the underlying cleavage structure of a society is so much more important than the details of electoral law that basically the same party system would arise regardless of the electoral system employed (cf. Cairns 1968, 78). Does anyone believe that the United States would remain a two-party system, even if it adopted the Israeli electoral system?

Similarly, to assert that electoral structure affects party competition in important and systematic ways does not imply that social structure is irrelevant. It might appear that this is exactly what Duverger's Law does imply -- bipartism in any society merely upon application of single-member districts -- but in fact that overstates Duverger's proposition and the institu tionalist development of it, where there has been an increasing appreciation of the interaction effects between social and electoral structure.

Duverger did take social structure more or less as a residual error, something that might perturb a party system away from its central tendency defined by electoral law. Later scholars, however, have considered the possibility that cleavage and electoral structures may interact. This has been the case in the string of papers that consider the importance of the geo graphic location of supporters of a given party (e.g., Kim and Ohn 1992; Rae 1971; Riker 1982; Sartori 1968) and also in a recent pair of works (Ordeshook and Shvetsova 1994; Powell 1982) that have included both sociological and institutional variables in regression analyses of cross national variations in the number of parties.

This paper follows the latter set of works in that it investigates the role of both social cleavages and electoral laws in determining the number of parties. We put particular emphasis on testing Ordeshook and Shvetsova's(1994) main finding-that there is a significant interaction between social heterogeneity and electoral structure. In order to put this claim to a stringent test, we employ a substantially different dataset-one that includes about twice as many countries as have previous studies, including a large number of third-world democracies-and model the impact of both electoral structure and presidential elections differently than have previous studies.

The structure of the paper is as follows. Section 1 sketches a hypothetical series of stages by which social cleavages are reduced to party-defining cleavages, noting that some stages are sensitive to the particularities of social structure, some to the details of electoral structure, and some to both. The sketch outline suggests the inclusion of both social and electoral vari ables in statistical analyses of the number of parties and Section 1 also reviews the work of Powell(1982) and Ordeshook and Shvetsova(1994), noted above, that takes this approach. Section 2 explains how our data. and methods differ from, and complement, previous efforts. Section 3 presents our results. Section 4 concludes.

1. Social Cleavages, Possible Parties, and Actual Parties

The effective number of elective or legislative parties in a polity can be thought of as the end product of a series of decisions by various agents that serve to reduce a large number of social differences, or cleavages, to a smaller number of party-defining cleavages.4 There are three broad stages to consider in this process of reduction: the translation of social cleavages into partisan preferences; the translation of partisan preferences into votes; and the translation of votes into seats.

In most institutionalist models, the first stage is not explored: there is an exogenously given number of parties with clear demarcating features (e.g., the positions they adopt along an ideological dimension), so that vot ers' preferences over parties are easily deducible. No party ever fails to get votes because it is too poor to advertise its position; no would-be party ever fails to materialize because it does not have the organizational sub strate (e.g., labor unions, churches) needed to launch a mass party. In an expanded view, of course, the creation of parties and the advertisement of their positions would be key points at which a reduction of the number of political players occurs. The multiplicity of possible or imaginable parties is reduced to an actual number of launched parties even before the electorate produces an effective number of vote-getting parties, and the electoral mechanism produces an effective number of seat-winning parties.

The reduction of launched parties to voted-for parties is the domain of strategic voting. Even if launched, a party still has to be perceived as viable in order to turn favorable preferences into votes. Whether it is so perceived depends on how many other parties are chasing after votes and on the de tails of electoral structure. In particular, Sartori's (1968) notion of the strength of an electoral system (where the strength in question is that of the incentives to coalesce that the electoral system produces) is useful here. The stronger the electoral system, the greater will be its efficiency in reduc ing an excessive number of known parties to a smaller effective number of voted-for parties. (Operational measures of the strength of an electoral system will be introduced below.)

Finally, the reduction of voted-for parties to seat-winning parties is typically a mechanical feature of the electoral system. The only substantial exceptions within individual electoral districts occur when votes are not pooled across all candidates from a given party, as in Taiwan or Colombia. In these systems, the distribution of a party's vote support across its candi dates or lists materially affects its seat allocation (cf. Cox and Shugart N.d.).

Given this general picture of how parties arise and of how the level of vote or seat concentration is set, one would imagine that studies of the effective number of elective or legislative parties would investigate the im pact of both social cleavages and electoral laws on party system fractional ization. However, among quantitative studies we are aware of only two that do this. The first of these, Powell (1982), looks only at legislative fractionalization while the second, Ordeshook and Shvetsova (1994), looks at both elective and legislative fractionalization.

Powell's (1982) work focuses on a set of 84 elections held in 27 mostly European countries during the period 1965-76. The dependent variable, legislative fractionalization, is measured by Rae's index (that is, 1 Σs2i, where si is the seat share of the ith party). The independent variables of primary interest are three measures of social heterogeneity-ethnic frac tionalization as measured by Rae's index (that is, 1 - Σg2i, where gi is the proportion of the population in ethnic group i); an index of agricultural minorities (coded 3, 2 or 1 if the agricultural population comprises 20 49%, 50-80%, or 5-19% of the total population); and an index of Catholic minorities (coded similarly to the agricultural index)-and two measures of electoral structure-the "strength" of the electoral system for legislative elections (coded 3 for single-member plurality elections, 2 for the Japanese, German and Irish systems, and 1 for proportional systems); and a dummy variable indicating whether or not the system is presidential (1 if yes, 0 if no). Regressing the independent variables just listed on the legislative fractionalization scores for each election, Powell (1982, 101) finds that "fractionalization is encouraged above all by ... nonmajoritarian electoral laws, but also by all of the heterogeneity measures, and discouraged by presidential executives. "

Ordeshook and Shvetsova (1994) consider several different data sets: Lijphart's (1990) sample of 20 Western democracies from 1945 to 1985 (representing 32 distinct electoral systems); an extension of this dataset covering elections in 23 Western democracies from 1945 to 1990 (repre senting 52 distinct electoral systems); and a further extension that includes Continental elections in the period 1918-39. The four dependent variables that Ordeshook and Shvetsova investigate are: the effective number of elective parties (ENPV = 1/Σv2i, where vi is party i's vote share); the effective number of legislative parties (ENPS = 1/Σs2i, where si is party i's seat share); the number of parties that receive at least 1 % of the vote in two or more successive elections; and the number of parties that secure one or more seats in two or more successive elections. They measure social structure chiefly in terms of ethnicity, calculating the effective number of ethnic groups (ENETH = 1/Σg2i, where gi is the proportion of the population in ethnic group i); and measure electoral system properties by the average district magnitude and by Taagepera and Shugart's (1989) "effective mag nitude" measure. They then use OLS regression to explain variations in their dependent variables (here we shall look just at ENPV), considering three basic specifications: (1) the institutionalist specification: ENPV as a function solely of the log of district magnitude, as in Taagepera and Shugart (1989); (2) the sociological specification: ENPV as a function solely of ethnic heterogeneity; and (3) the interactive specification: ENPV as a func tion of the product of ethnic heterogeneity and district magnitude. They find that the interactive model does best in explaining the data, summarizing their findings as follows:

... if the effective number of ethnic groups is large, political systems become especially sensitive to district magnitude. But if ethnic fractionalization is low, then only especially large average district magnitudes result in any 'wholesale' increase in formally organized parties. Finally, if district magnitude equals one, then the party system is relatively 'impervious' to ethnic and linguistic heterogeneity ... (Ordeshook and Shvetsova 1994, 122).

Thus, whereas Powell (1982, 81) had success with an additive specification, Ordeshook and Shvetsova find an interactive model to be superior.

Why should an interactive model work well? One answer runs as fol lows. A polity will have many parties only if it both has many cleavages and has a permissive enough electoral system to allow political entrepreneurs to base separate parties on these cleavages. Or, to turn the formulation around, a polity can have few parties either because it has no need for many (few cleavages) or poor opportunities to create many (a strong electoral system). If these claims are true, they would rule out models in which the number of parties depends only on the cleavage structure, or only on the electoral system, or only on an additive combination of these two considerations.

Plausible though this formulation might be, it still leaves several ques tions unanswered. First, and most important, is the question of empirical evidence. Thus far we have one study in which an additive specification seems to work well (Powell) and one study in which an interactive specifi cation proves superior (Ordeshook and Shvetsova). The latter study, more over, is based largely on European evidence, and one might well ask what would happen if India (or other socially diverse third-world countries with strong electoral systems) were added. Since India appears to have lots of social cleavages and also to have lots of parties, would the addition of this (kind of) case to the analysis not bolster the importance of social heteroge neity and, perhaps, point more toward an additive rather than an interactive specification? Second, there is also the issue of what the form of the interac tion between electoral and cleavage structure is. Perhaps the effective num ber of elective parties (ENPV) should equal the minimum of (1) the number of parties that the cleavage structure will support (loosely following Taage pera and Grofman 1985, we might say this number was C + 1, where C is the number of cleavages); and (2) the number of parties that the electoral system will support (following the "generalized Duverger's Law" of Taagepera and Shugart 1989, we might say this number was 2.5 + 1.25 log10M, where M is the district magnitude). That is, perhaps the equation should be something like ENPV = MIN[2.5 + 1.25 log10M, C + 1]. Or, perhaps the form of the interaction is as Ordeshook and Shvetsova specify it, a simple product of factors reflecting electoral strength and number of cleavages. In the next two sections, we investigate both these questions, especially the first.

2. Data and Methods

In considering the interaction between social heterogeneity and electoral permissiveness, our analytical strategy is to look at different data than did Ordeshook and Shvetsova (1994), using different operational measures of key variables. The notion is that, if their basic finding of a significant interaction is robust to these changes, then we can have more confidence in it. The most important differences between our analysis and Ordeshook and Shvetsova's are as follows: we include a larger number of countries, including many third-world democracies; we measure the strength of an electoral system by employing separate measures of lower-tier district mag nitude and upper-tier characteristics, rather than combining these two fac tors (in an "effective magnitude") or ignoring upper tiers (by taking a simple average of the district magnitudes); and we include variables tapping the influence of presidential elections (if any) in the system. Let us consider each point in turn.

Case Selection

We have taken as a case every polity with an election in the 1980s (defined as 1980-90 inclusive) that qualifies as 'free' by Freedom House's score on political rights (either a 1 or a 2); if a polity has multiple such elections in the 1980s, we have taken the one closest to 1985. These crite ria of selection mean that we have a substantially more diverse sample than do Ordeshook and Shvetsova (or Powell before them), one that includes India, Venezuela, Mauritius, and many other third-world countries (see the Appendix). The total number of countries included is 54. As there is only one observation per country, our sample can also be described as having observations on 54 electoral systems.

Measuring Electoral Structure

We differ from Ordeshook and Shvetsova (1994) and most of the previ ous literature in that we do not use average magnitude or Taagepera and Shugart's (1989) 'effective magnitude' as our main indicator of the strength of an electoral system. Instead, we use two variables, one to describe the magnitude of the lower-tier districts, and one to describe the impact of the upper tier.

The lower-tier variable that we use is based on the magnitude of the median legislator's district. An example may help to clarify why we use this variable rather than simply the average district magnitude. Suppose an electoral system has just two districts, one returning a single member and one returning 100 members. The average district magnitude in this system is (100 + 1)/2 = 50.5. But this process of averaging, in which each district counts equally, does not correspond to the usual way in which the effective number of parties is calculated. To see this, suppose that there are 100 voters in the 1-seat district, who split equally between two parties, while there are 10,000 voters in the 100-seat district, who split equally between 10 parties. In this case, the effective number of parties in the 1-seat district, the 100-seat district, and the nation as a whole are respectively 2, 10, and almost 10. The national effective number of parties is much closer to the effective number of parties in the large district because the votes from both districts are simply added to arrive at the national vote totals, and there are 100 times more voters in the large district than in the small. The national effective number of parties, in other words, is a weighted average of the district figures, in which larger districts get more weight. Accordingly, it seems natural to use a similarly weighted measure of the central tendency in district magnitudes. We choose to weight each district by the number of legislators from that district (which, if there is no malapportionment in the system, and turnout is equal across districts, will correspond to the weights used in calculating the national effective number of parties). We also have chosen to use medians rather than means. In the example at hand, this yields a figure of 100: there are 101 legislators, of whom 100 are elected from a district of magnitude 100; the magnitude of the median legislator's district is thus 100. As it turns out, using the average of the legislator's district magnitudes, rather than the median, has virtually no impact on the results that follow. Finally, we follow Taagepera and Shugart (1989) and take the logarithm of the median legislator's district's magnitude, to produce a variable we denote LML.

The upper-tier variable that we use, denoted UPPER, equals the percentage of all assembly seats allocated in the upper tier(s) of the polity. It ranges from zero for polities without upper tiers to a maximum of 50% for Germany. The idea here is that instead of attempting to deduce how the existence of upper tier affects the "effective magnitude" of a system, we simply let the upper tiers speak for themselves. Because all but one of the upper tiers in our sample are compensatory-designed specifically to increase the proportionality of the overall result-we can avoid some of the complexities of Taagepera and Shugart's "effective magnitude," which attempts to put the effects of compensatory and additional seats on a com mon metric (Taagepera and Shugart 1989, ch. 12).

Presidentialism

Several previous studies-e.g., Jones (1994), Lijphart (1994), Main waring and Shugart (1995), Powell (1982)-have included a code for presi dential elections in investigations of legislative fractionalization. So do we. As our coding of this variable differs from these previous studies, however, we discuss it at some length.

The simplest way to code presidentialism is with a dummy variable (1 for presidential systems, 0 for parliamentary), as do Lijphart (1994) and Powell (1982). The problem with this approach is that there are different kinds of presidential elections (runoff, plurality), held at different times relative to the legislative elections (concurrently, nonconcurrently), and these factors plausibly matter. Thus, other scholars-such as Jones (1994), Mainwaring and Shugart (1995), Shugart (1995), Shugart and Carey (1992) -have devel oped more elaborate schemes. Our approach, which follows Shugart and Carey (1992) in general conception but differs in the details of implementa tion, takes the influence a presidential election exerts on a legislative election as depending on two factors: the proximity of the two elections; and the degree of fractionalization of the presidential election.

Proximity is a matter of degree. If the presidential and legislative elections are concurrent, then proximity is maximal. Here, we take the maxi mum value of proximity to be unity (so concurrent elections are "1 00% proximal," so to speak). At the other end of the scale are legislative elections held in complete isolation from presidential elections-i.e., in non presidential systems. Such legislative elections are not at all proximal to a presidential election-so they are coded as of zero proximity. In between these two extremes are presidential systems with nonconcurrent elections. If we denote the date of the legislative election by Lt, the date of the preced ing presidential election by Pt-1, and the date of the succeeding presidential election by Pt+1, then the proximity value is PROXIMITY = 2*|(Lt - Pt-1)/(Pt+1 - Pt-1) - 1/2|. This formula expresses the time elapsed between the preceding presidential election and the legislative election (Lt - Pt-1), as a fraction of the presidential term (Pt+1, - Pt-1). Subtracting 1/2 from this elapsed time fraction, and then taking the absolute value, shows how far away from the midterm the legislative election was held. The logic of the formula is as follows: the least proximal legislative elections are those held at midterm. This particular formula gives a proximity value of zero to these elections, which equates them with the totally isolated elections of nonpres idential systems. The most proximal nonconcurrent elections are those held just before or just after a presidential election. The formula above gives them a proximity value that approaches one, the same value given to concurrent elections.

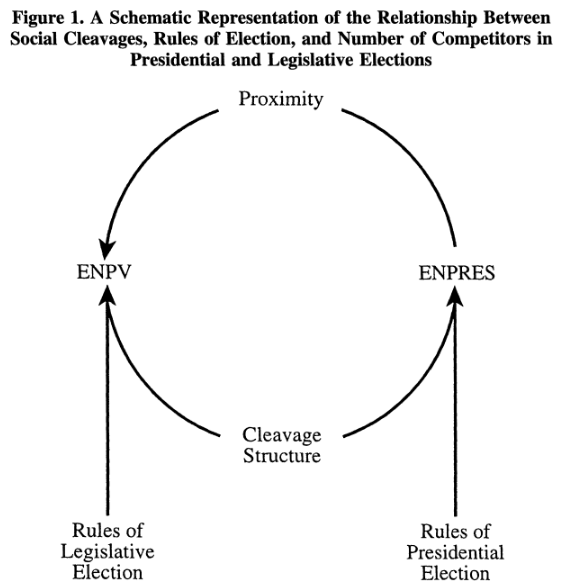

The proximity of the presidential election to the legislative election is a necessary condition for the former to influence the latter. But the nature of that influence depends on the nature of the presidential election. One approach to coding the nature of the presidential election is institutional. Mainwaring and Shugart (1995), for example, introduce variables that dis tinguish three classes of presidential elections: concurrent plurality, major ity runoff, and other. Although we report some results in a footnote that follow this route, our approach is different. Our point of departure is the notion that both presidential and legisla tive election results convey information about the impact of social cleav ages and electoral laws. To put it another way, if we denote the effective number of presidential candidates by ENPRES, and the effective number of elective parties in the legislative election by ENPV, then both ENPRES and ENPV may be thought of as dependent variables-products of social and electoral structure-along the lines of Figure 1.

There are three things to note about Figure 1. First, the picture assumes that the effect of the presidential election on the legislative election domi nates that of the legislative election on the presidential: thus there is an arrow from ENPRES to ENPV but not one going in the reverse direction. In reality, there no doubt are reverse causal arrows of the kind omitted from Figure 1. But we believe that the direction of influence is primarily from executive to legislative elections, and making this assumption facilitates econometric estimation of the system of equations implied by Figure 1. In particular, one can first estimate an equation determining ENPRES and then estimate an equation-in which ENPRES appears as a regressor-de termining ENPV (see below).

The second thing to note is that the influence of presidential on legisla tive elections is mediated through the effective number of presidential can didates, ENPRES, and does not include a direct impact of presidential rules on legislative fractionalization, as does the Mainwaring and Shugart (1995) formulation. Our justification for this runs as follows. Imagine a presiden tial election held under runoff rules that nonetheless-perhaps because the country is dominated by a single cleavage, perhaps for reasons idiosyncratic to the particular election-ends up as a two-way race. Given that there are just two candidates in the presidential race, we expect the same kind of influence as would be produced by an otherwise similar plurality race. The nature of the coattail opportunities that face legislative candidates should be similar, the nature of the advertising economies of scale that might be exploited should be similar, and so forth. It is hard to see why the presiden tial rules themselves, having failed to produce the expected result in the presidential race, would nonetheless exert some direct influence on the leg islative race. Thus, we prefer to include ENPRES as a regressor in the equation for ENPV, rather than including descriptors of presidential election rules (these rules, of course, do have an indirect impact via their influ ence on ENPRES). All told, our expectation is that legislative elections that are highly proximal to presidential elections should have a lower effective number of parties, but how much lower should depend on ENPRES. Thus we include both PROXIMITY and PROXIMITY*ENPRES in the analysis.

A final point to note about Figure 1 is that it presupposes an interaction between electoral and social structure, both in the production of ENPV and in the production of ENPRES. If there is such an interaction in legislative elections, as Ordeshook and Shvetsova (1994) claim, then there should also be an interaction in presidential elections.

Specifying the Equations

Having discussed the main differences of data and operationalization between our analysis and Ordeshook and Shvetsova's, we can turn to the issue of how we specify the relations of interest. We shall consider first the effective number of legislative parties (ENPS), then the effective number of elective parties (ENPV), and finally the effective number of presidential candidates (ENPRES).

In investigating the first of these dependent variables (ENPS), we are interested in the purely mechanical features of how the legislative electoral system translates votes into seats. Accordingly, we include ENPV on the right-hand side (cf. Coppedge 1995). Indeed, in our view, the proper formu lation is one in which ENPS would equal ENPV, were the electoral system perfectly proportional, with stronger electoral systems reducing ENPS be low ENPV. Thus, we run the following regression:

If the electoral system employs single-member districts (so LML = 0) and has no upper tier (so UPPER = 0), then it is maximally strong, and only a fraction β0 of ENPV is added to α to give the predicted effective number of legislative parties in the system. As LML and UPPER increase, the system becomes more permissive and the fraction of ENPV that translates into seats should be greater. That is, the coefficients on ENPV*LML (i.e., β1) and on ENPV*UPPER (i.e., β2) should both be positive. One way to inter pret this regression is simply as a check on the validity of our measures LML and UPPER. If LML properly measures the central tendency in lower tier district magnitudes and UPPER really catches the impact of upper tiers, then the coefficients associated with both should be significant!

In the analysis of the effective number of elective parties, ENPV, we run five specifications: a pure institutionalist specification, with only vari ables pertaining to the legislative electoral system or the impact of presiden tial elections; a pure sociological model, with only a variable tapping into social heterogeneity (specifically, ENETH, the effective number of ethnic groups, used by Ordeshook and Shvetsova); an additive model in which both sets of variables are included; an additive/interactive model in which an interaction term (between LML and ENETH) is added to the previous specification; and an interactive model in which the linear terms for LML and ENETH are omitted but the interaction term LML*ENETH is kept.

Finally, our analysis of the effective number of presidential candidates is as suggested in Figure 1. The main regressors are a dummy variable identifying runoff systems (RUNOFF), the effective number of ethnic groups (ENETH), and their interaction (RUNOFF*ENETH).

3. Results

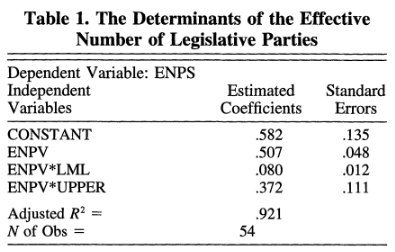

Our results are displayed in Tables 1, 2, and 3. Table 1 shows, not surprisingly, that a fair amount of the variance (93%) in the effective num ber of parliamentary parties can be explained by just ENPV and interactions between ENPV and two indicators of the strength of the electoral system - LML and UPPER. All variables have the expected sign and are statistically discernible from zero at about the .001 level or better. One way to explain the substantive impacts implied by the results in Table 1 is to compare two hypothetical systems, in neither of which there is an upper tier. System A has single-member districts, hence LML = 0. System B has ten-seat dis tricts, hence LML = 2.3. Suppose that both systems have ENPV = 3 in a particular election. The stronger system (A) is predicted to reduce this number of elective parties by almost a full (effective) party, to 2.09 (shades of the United Kingdom in the 1980s!). The weaker system (B) is predicted to reduce the three effective parties competing in the election by much less, to 2.64 legislative parties. The substantive importance of this difference might vary from situation to situation, but it certainly suggests an important change from essentially a two-party legislative system with mostly single-party governments to a two-and-a-half or three-party legislative system with coalition governments as the norm.

The results in Table 2 show the results for the five equations estimating the effective number of elective parties (ENPV) outlined in the previous section. In running these regressions, we have omitted electoral systems with fused votes - that is, systems in which the voter casts a single vote for a slate which includes candidates for executive and legislative offices. The reason for omitting such systems is that they change the meaning of essentially all the institutional regressors. For example, do voters in such systems respond to the district magnitude at the legislative level or at the presidential level? Fused-vote systems really need to be analyzed separately (see Shugart 1985 for the case of Venezuela, which has a fused vote for senate and house races) but we do not attempt to do so here: we just omit the three cases of executive-legislative fused votes in our sample-Bolivia, Honduras, and Uruguay.'9 This reduces our number of observations to 51 for the regressions in Table 2. We shall discuss each briefly in turn.

The first model, with only institutional variables, explains about 61% of the variance in our sample of ENPV values. All coefficients are of the expected sign and significant at the .05 level or better. The second model, with only the effective number of ethnic groups (ENETH) as a regressor, produces a poor fit (an adjusted R2 of .01) and an insignificant coefficient and regression. The third model, which combines the regressors from the first two, shows little change in the coefficients of the institutional variables but produces a coefficient on ENETH that is statistically significant at the .05 level. Appar ently, proper controls for electoral structure are important in discerning any independent additive effect due to ethnic heterogeneity. The fourth model - which adds to the third an interaction term, LML*ENETH - reduces the coefficients on LML and ENETH to statistically insignificant values, while producing a substantial and statistically significant positive coefficient on the interaction term (LML*ENETH), together with little change in the coefficients of the remaining variables. Finally, the fifth model, in which the variables LML and ENETH are omitted, but their inter action is retained, produces a somewhat smaller interaction coefficient (but a substantially smaller interaction standard error), with other coefficients largely unchanged. If one chooses among specifications according to which produces the largest adjusted R2 (not necessarily recommended; see the discussion in Kennedy 1994), then the last specification - with an adjusted R2 of .69 - is the best.

We have also investigated a different formulation for the interactive term, using the minimum of LML and ENETH instead of their product. Substituting this minimum term for LML*ENETH in the last model produces little change in any of the other coefficients or in the overall fit of the equation. It is thus difficult on the basis of this study to say much one way or another about whether the form of the interaction should be thought of as a product or a minimum.

Finally, Table 3 displays results for three regressions that take ENPRES as the dependent variable. The first model is additive, using RUNOFF and ENETH as regressors. As can be seen, neither regressor is statistically sig nificant and the regression as a whole sports a negative adjusted R2 (regres sions with just RUNOFF and just ENETH are also insignificant). The sec ond model adds the interaction term, RUNOFF*ENETH, to the first. The linear terms remain insignificant (albeit reversing sign) but the interaction term is appropriately signed and significant. The last model drops the linear terms, keeping only the interaction; the coefficient on the interaction term is again positive and statistically discernible from zero in a one-tailed test at the .05 level.

Two questions that might arise about the series of results just presented are whether our results hold for other measures of social diversity and whether our results hold both for the mostly-European industrialized de mocracies (investigated in previous studies) and for the mostly-non-European developing democracies (that we have added to the analysis). The answer to both questions is affirmative. If, instead of the effective number of ethnic groups, one uses the effective number of language groups as a measure of social diversity, one finds qualitatively similar results. If one removes the 20 mostly-European democracies studied -by Rae (1971), Lijphart (1990), and Ordeshook and Shvetsova (1994) from the analysis, leaving a sample of 34 mostly non-European developing countries, one again finds qualitatively similar results in all analyses.

4. Conclusion

The results presented in the previous section pertaining to legislative elections are remarkably similar to those generated by Ordeshook and Shvetsova (1994). Despite using a different data set-one that included many new and developing democracies rather than concentrating on the long-term democracies-and despite several differences in operationaliza tion and specification, the basic result holds up: the effective number of parties appears to depend on the product of social heterogeneity and electoral permissiveness, rather than being an additive function of these two factors. The intuitive formulation of this finding is that a polity can tend toward bipartism either because it has a strong electoral system or because it has few cleavages. Multipartism arises as the joint product of many ex ploitable cleavages and a permissive electoral system.

If this general conclusion is valid, it ought to hold, not just for elections to the lower house of the national legislature, but also for other elections. And we do find a bit of evidence consistent with the notion that the effective number of presidential candidates is an interactive product of social and electoral structure. In particular, elections that are both held under more permissive rules (runoff rather than plurality) and occur in more diverse societies (with a larger effective number of ethnic groups) are those that tend to have the largest fields of contestants for the presidency.

It is worth discussing why this finding - that the size of the party system depends interactively on social and electoral structure - is important and has merited the effort of reexamination and extension. First, it clearly differs from the more purely sociological formulations noted at the outset of the paper, in which the cleavage structure drives both the choice of an electoral system and the number of parties. For, under such a formulation, a polity with many cleavages always chooses a permissive electoral system, so that the strength of the electoral system should have had no discernible impact after controlling for the cleavage structure. The measure of cleavage structure employed here is crude, so that one cannot confidently reject the purely sociological approach based on this study, but certainly our results lend no support.

Second, that there is an interaction between electoral strength and so cial heterogeneity in the genesis of political parties also argues against purely institutionalist approaches. Consider, for example, Lijphart's (1994) magisterial examination of changes in postwar democratic electoral systems and the subsequent changes in number of parties. Often he found that increases in the permissiveness of an electoral system did not subsequently give rise to an increase in the number of parties. On a purely institutionalist account, this would count against the importance of electoral law. Taking account of the interaction between social and electoral structure, however, finding no increase in the number of parties after increasing the permis siveness of the electoral system counts as evidence against the importance of electoral structure only if one believes that the previous electoral system had impeded the exploitation of extant cleavages in the society, so that it was actually holding the number of parties below what it would be with a more permissive system. Absent such a belief, one would not expect a weakening of the electoral system to lead to increases in the number of parties, and so one would not count failure to observe such an increase as evidence of the frailty of electoral laws in conditioning political life. Simi larly, finding that an increase in the strength of an electoral system does not produce a contraction in the party system is telling evidence only if the number of parties under the old system exceeds the "carrying capacity" of the new system.

Finally, we should note some directions for further research that our works suggests. One follows directly from the remarks just made: perhaps there is room for a reanalysis of Lijphart's (1994) findings with social heter ogeneity taken into account. Another follows from a question posed but left unanswered above: what precisely should the form of the interaction between social and electoral structure be? To address this question would require a substantially larger dataset than that we have compiled here. A third possible direction for research follows from the general observation that electoral studies ought to move toward constituency-level evidence (e.g., Cox and Shugart 1991; Taagepera and Shugart 1989, 213-14). Clearly, the key electoral factors (e.g., district magnitude) can vary widely within a given nation. Just as clearly, it is also possible to find substantial variation across a given nation's electoral constituencies in ethnic, linguis tic, and religious heterogeneity. These observations suggest that it may be fruitful in further investigations of the interaction (or lack thereof) between social and electoral structure, to use constituency-level electoral returns and constituency-level indicators of social diversity.