고정 헤더 영역

상세 컨텐츠

본문

THE TRANSFORMATION OF CLEAVAGE STRUCTURES INTO PARTY SYSTEMS

Conditions for the Channelling of Opposition

Thus far, we have focused on the emergence of one cleavage at a time and only incidentally concerned ourselves with the growth of cleavage systems and their translations into constellations of political parties. But cleavages do not translate themselves into party oppositions as a matter of course: there are considerations of organizational and electoral strategy; there is the weighing of pay-offs of alliances against losses through split-offs; and there is the successive narrowing of the mobilization market through the time sequences of organizational efforts. Here we enter into an area of crucial concern in current theorizing and research, an area of great fascination crying out for detailed co-operative research. Very much needs to be done in reanalysing the evidence for each national party system and even more in exploring the possibilities of fitting such findings into a wider framework of developmental theory. We cannot hope to deal exhaustively with such possibilities of comparison in this volume and shall limit ourselves to a discussion of a few characteristic developments and suggest a rough typology.

How does a socio-cultural conflict get translated into an opposition between parties? To approach an understanding of the variations in such processes of translation we have to sift out a great deal of information about the conditions for the expression of protest and the representation of interests in each society.

First, we must know about the traditions of decision-making in the polity: the prevalence of conciliar versus autocratic procedures of central government, the rules established for the handling of grievances and protests, the measures taken to control or to protect political associations, the freedom of communication, and the organization of demonstrations.

Second, we must know about the channels for the expression and mobilization of protest: Was there a system of representation and if so how accessible were the representatives, who had a right to choose them, and how were they chosen? Was the conflict primarily expressed through direct demonstrations, through strikes, sabotage, or open violence, or could it be channelled through regular elections and through pressures on legitimately established representatives?

Third, we need information about the opportunities, the pay-offs, and the costs of alliances in the system: How ready or reluctant were the old movements to broaden their bases of support and how easy or difficult was it for new movements to gain representation on their own?

Fourth and finally, we must know about the possibilities, the implications, and the limitations of majority rule in the system: What alliances would be most likely to bring about majority control of the organs of representation and how much influence could such majorities in fact exert on the basic structuring of the institutions and the allocations within the system?

The Four Thresholds

These series of questions suggest a sequence of thresholds in the path of any movement pressing forward new sets of demands within a political system.

First, the threshold of legitimation: Are all protests rejected as conspiratorial, or is there some recognition of the right of petition, criticism, and opposition?

Second, the threshold of incorporation: Are all or most of the supporters of the movement denied status as participants in the choice of representatives or are they given political citizenship rights on a par with their opponents?

Third, the threshold of representation: Must the new movement join larger and older movements to ensure access to representative organs or can it gain representation on its own?

Fourth, the threshold of majority power: Are there built-in checks and counterforces against numerical majority rule in the system or will a victory at the polls give a party or an alliance power to bring about major structural changes in the national system?

The early comparative literature on the growth of parties and party systems focused on the consequences of the lowering of the two first thresholds: the emergence of parliamentary opposition and a free press and the extension of the franchise. Tocqueville and Ostrogorski, Weber and Michels, all in their various ways, sought to gain insight into that central institution of the modern polity, the competitive mass party.* The later 14 literature, particularly since the 1920s, changed its focus to the third and the fourth threshold: the consequences of the electoral system and the structure of the decision-making arena for the formation and the functioning of party systems. The fierce debates over the pros and cons of electoral systems stimulated a great variety of efforts at comparative analysis, but the heavy emotional commitments on the one or the other side often led to questionable interpretations of the data and to overhasty generalizations from meagre evidence. Few of the writers could content themselves with comparisons of sequences of change in different countries. They wanted to influence the future course of events, and they tended to be highly optimistic about the possibilities of bringing about changes in established party systems through electoral engineering. What they tended to forget was that parties once established develop their own internal structure and build up long-term commitments among core supporters. The electoral arrangements may prevent or delay the formation of a party, but once it has been established and entrenched, it will prove difficult to change its character simply through variations in the conditions of electoral aggregation. In fact, in most cases it makes little sense to treat electoral systems as independent variables and party systems as dependent. The party strategists will generally have decisive influence on electoral legislation and opt for the systems of aggregation most likely to consolidate their position, whether through increases in their representation, through the strengthening of the preferred alliances, or through safeguards against splinter movements. In abstract theoretical terms it may well make sense to hypothesize that simple majority systems will produce two-party oppositions within the culturally more homogeneous areas of a polity and only generate further parties through territorial cleavages, but the only convincing evidence of such a generalization comes from countries with a continuous history of simple majority aggregations from the beginnings of democratic mass politics. There is little hard evidence and much uncertainty about the effects of later changes in election laws on the national party system: one simple reason is that the parties already entrenched in the polity will exert a great deal of influence on the extent and the direction of any such changes and at least prove reluctant to see themselves voted out of existence.

Any attempt at systematic analysis of variations in the conditions and the strategies of party competition must start out from such differentiations of developmental phases. We cannot, in this context, proceed to detailed country-by-country comparisons but have to limit ourselves to a review of evidence for two distinct sequences of change: the rise of lower-class movements and parties and the decline of régime censitaire parties.

The Rules of the Electoral Game

The early electoral systems all set a high threshold for rising parties. It was everywhere very difficult for working-class movements to gain representation on their own, but there were significant variations in the openness of the systems to pressures from the new strata. The second ballot systems so well known from the Wilhelmine Reich and from the Third and the Fifth French Republics set the highest possible barrier, absolute majority, but at the same time made possible a variety of local alliances among the opponents of the Socialists: the system kept the new entrants underrepresented, yet did not force the old parties to merge or to ally themselves nationally. The blatant injustices of the electoral system added further to the alienation of the working classes from the national institutions and generated what Giovanni Sartori has described as systems of centrifugal pluralism:15 one major movement outside the established political arena and several opposed parties within it.

Simple-majority systems of the British-American type also set high barriers against rising movements of new entrants into the political arena; however, the initial level is not standardized at 50 per cent of the votes cast in each constituency but varies from the outset with the strategies adopted by the established parties. If they join together in defence of their common interests, the threshold is high; if each competes on its own, it is low. In the early phases of working-class mobilization, these systems have encouraged alliances of the Lib-Lab type. The new entrants into the electorate have seen their only chances of representation as lying in joint candidatures with the more reformist of the established parties. In later phases distinctly Socialist parties were able to gain representation on their own in areas of high industrial concentration and high class segregation, but this did not invariably bring about counteralliances of the older parties. In Britain, the decisive lower-class breakthrough came in the elections of 1918 and 1922. Before World War I the Labour party had presented its own candidates in a few constituencies only and had not won more than 42 out of 670 seats; in 1918 they suddenly brought forth candidates in 388 constituencies and won 63 of them and then in 1922 advanced to 411 constituencies and 142 seats. The simple-majority system did not force an immediate restructuring of the party system, however. The Liberals continued to fight on their own and did not give way to the Conservatives until the emergency election of 1931. The inveterate hostilities between the two established parties helped to keep the average threshold for the newcomers tolerably low, but the very ease of this process of incorporation produced a split within the ranks of Labour. The currency crisis forced the leaders to opt between their loyalty to the historical nation and their solidarity with the finally mobilized working class.

This brings us to a crucial point in our discussion of the translation of cleavage structure into party systems: the costs and the pay-offs of mergers, alliances, and coalitions. The height of the representation threshold and the rules of central decision-making may increase or decrease the net returns of joint action, but the intensity of inherited hostilities and the openness of communications across the cleavage lines will decide whether mergers or alliances are actually workable. There must be some minimum of trust among the leaders, and there must be some justification for expecting that the channels to the decisionmakers will be kept open whoever wins the election. The British electoral system can only be understood against the background of the long-established traditions of territorial representation; the MP represents all his constituents, not just those who voted him in. But this system makes heavy demands on the loyalty of the constituents: in two-party contests up to 49 per cent of them may have to abide by the decisions of a representative they did not want; in three-cornered fights, as much as 66 percent.

Such demands are bound to produce strains in ethnically, culturally, or religiously divided communities: the deeper the cleavages the less the likelihood of loyal acceptance of decisions by representatives of the other side. It was no accident that the earliest moves towards Proportional Representation came in the ethnically most heterogeneous of the European countries, Denmark (to accommodate Schleswig-Holstein), as early as 1855, the Swiss cantons from 1891 onward, Belgium from 1899, Moravia from 1905, and Finland from 1906.16 The great historian of electoral systems, Karl Braunias, distinguishes two phases in the spread of PR: the minority protection phase before World War I and the anti-socialist phase in the years 17 immediately after the armistice. In linguistically and religiously divided societies majority elections could clearly threaten the continued existence of the political system. The introduction of some element of minority representation came to be seen as an essential step in a strategy of territorial consolidation.

As the pressures mounted for extensions of the suffrage, demands for proportionality were also heard in the culturally more homogeneous nation-states. In most cases the victory of the new principle of representation came about through a convergence of pressures from below and from above. The rising working class wanted to lower the threshold of representation to gain access to the legislatures, and the most threatened of the old-established parties demanded PR to protect their positions against the new waves of mobilized voters under universal suffrage. In Belgium the introduction of graduated manhood suffrage in 1893 brought about an increasing polarization between Labour and Catholics and threatened the continued existence of the Liberals; the introduction of PR restored some equilibrium to the system. The history of the struggles over electoral procedures in Sweden and in Norway tells us a great deal about the consequences of the lowering of one threshold for the bargaining over the level of the next. In Sweden, the Liberals and the Social Democrats fought a long fight for universal and equal suffrage and at first also advocated PR to ensure easier access to the legislature. The remarkable success of their mobilization efforts made them change their strategy, however. From 1904 onward they advocated majority elections in single-member constituencies. This aroused fears among the farmers and the urban Conservatives, and to protect their interests they made the introduction of PR a condition for their acceptance of manhood suffrage. As a result the two barriers fell together: it became easier to enter the electorate and easier to gain representation. In Norway there was a much longer lag between the waves of mobilization. The franchise was much wider from the outset, and the first wave of peasant mobilization brought down the old regime as early as in 1884. As a result the suffrage was extended well before the final mobilization of the rural proletariat and the industrial workers under the impact of rapid economic change. The victorious radical-agrarian Left felt no need to lower the threshold of representation and in fact helped to increase it through the introduction of a two-ballot system of the French type in 1906. There is little doubt that this contributed heavily to the radicalization and the alienation of the Norwegian Labour party. By 1915 it had gained 32 per cent of all the votes cast but was given barely 15 per cent of the seats. The Left did not give in until 1921. The decisive motive was clearly not just a sense of equalitarian justice but the fear of rapid decline with further

advances of the Labour party across the majority threshold. In all these cases high thresholds might have been kept up if the parties of the property-owning classes had been able to make common cause against the rising working-class movements. But the inheritance of hostility and distrust was too strong. The Belgian Liberals could not face the possibility of a merger with the Catholics, and the cleavages between the rural and the urban interests went too deep in the Nordic countries to make it possible to build up any joint antisocialist front. By contrast, the higher level of industrialization and the progressive merger of rural and urban interests in Britain made it possible to withstand the demand for a change in the system of representation. Labour was seriously underrepresented only during a brief initial period, and the Conservatives were able to establish broad enough alliances in the counties and the suburbs to keep their votes well above the critical point.

A MODEL FOR THE GENERATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARTY SYSTEM

Four Decisive Dimensions of Opposition

This review of the conditions for the translation of sociocultural cleavages into political oppositions suggests three conclusions.

First, the constitutive contrasts in the national system of party constellations generally tended to manifest themselves before any lowering of the threshold of representation. The decisive sequences of party formation took place at the early stage of competitive politics, in some cases well before the extension of the franchise, in other cases on the very eve of the rush to mobilize the finally enfranchised masses.

Second, the high thresholds of representation during the phase of mass politicization set severe tests for the rising political organizations. The surviving formations tended to be firmly entrenched in the inherited social structure and could not easily be dislodged through changes in the rules of the electoral game.

Third, the decisive moves to lower the threshold of representation reflected divisions among the established régime censitaire parties rather than pressures from the new mass movements. The introduction of PR added a few additional splinters but essentially served to ensure the separate survival of parties unable to come together in common defence against the rising contenders of majority power.

What happened at the decisive party-forming phase in each national society? Which of the many contrasts and conflicts were translated into party oppositions, and how were these oppositions built into stable systems?

This is not the place to enter into detailed comparisons of developmental sequences nation by nation. Our task is to suggest a framework for the explanation of variations in cleavage bases and party constellations.

In the abstract schema set out in Fig. 9.2 we distinguished four decisive dimensions of opposition in Western politics:

two of them were products of what we called the National Revolution (1 and 2);

and two of them were generated through the Industrial Revolution (3 and 4).

In their basic characteristics the party systems that emerged in the Western European politics during the early phase of competition and mobilization can be interpreted as products of sequential interactions between these two fundamental processes of change.

Differences in the timing and character of the National Revolution set the stage for striking divergencies in the European party system. In the Protestant countries the conflicts between the claims of the State and the Church had been temporarily settled by royal fiats at the time of the Reformation, and the processes of centralization and standardization triggered off after 1789 did not immediately bring about a conflict between the two. The temporal and the spiritual establishments were at one in the defence of the central nation-building culture but came increasingly under attack by the leaders and ideologists of countermovements in the provinces, in the peripheries, and within the underprivileged strata of peasants, craftsmen, and workers. The other countries of Western Europe were all split to the core in the wake of the secularizing French Revolution and without exception developed strong parties for the defence of the Church, either explicitly as in Germany, the Low Countries, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, and Spain or implicitly as in the case of the Right in France.

Differences in the timing and character of the Industrial Revolution also made for contrasts among the national party system in Europe.

Conflicts in the commodity market tended to produce highly divergent party alliances in Europe. In some countries the majority of the market farmers found it possible to join with the owner interests in the secondary sector of the economy; in others the two remained in opposition to each other and developed parties of their own. Conflicts in the labour market, by contrast, proved much more uniformly divisive: all countries of Western Europe developed lower-class mass parties at some point or other before World War I. These were rarely unified into one single working-class party. In Latin Europe the lowerclass movements were sharply divided among revolutionary anarchist, anarcho-syndicalist, and Marxist factions on the one hand and revisionist socialists on the other. The Russian Revolution of 1917 split the working-class organizations throughout Europe. Today we find in practically all countries of the West divisions between Communists, left Socialist splinters, and revisionist Social Democrat parties.

Our task, however, is not just to account for the emergence of single parties but to analyse the processes of alliance formation that led to the development of stable systems of political organizations in country after country. To approach some understanding of these alliance formations, we have to study the interactions between the two revolutionary processes to change in each polity: How far had the National Revolution proceeded at the point of the industrial take-off and how did the two processes of mobilization, the cultural and the economic, affect each other, positively by producing common fronts or negatively by maintaining divisions?

The decisive contrasts among the Western party systems clearly reflect differences in the national histories of conflict and compromise across the first three of the four cleavage lines distinguished in our analytical schema: the centre-periphery, the StateChurch, and the land-industry cleavages generated national developments in divergent directions, while the owner-worker cleavage tended to bring the party systems closer to each other in their basic structure. The crucial differences among the party systems emerged in the early phases of competitive politics, before the final phase of mass mobilization. They reflected basic contrasts in the conditions and sequences of nationbuilding and in the structure of the economy at the point of take-off towards sustained growth. This, to be sure, does not mean that the systems vary exclusively on the Right and at the centre, but are much more alike on the Left of the political spectrum. There are working-class movements throughout the West, but they differ conspicuously in size, in cohesion, in ideological orientation, and in the extent of their integration into, or alienation from, the historically given national policy. Our point is simply that the factors generating these differences on the left are secondary. The decisive contrasts among the systems had emerged before the entry of the working-class parties into the political arena, and the character of these mass parties was heavily influenced by the constellations of ideologies, movements, and organizations they had to confront in that arena.

A Model in Three Steps

To understand the differences among the Western party systems we have to start out from an analysis of the situation of the active nation-building élite on the eve of the breakthrough to democratization and mass mobilization: What had they achieved and where had they met most resistance? What were their resources, who were their nearest allies, and where could they hope to find further support? Who were their enemies, what were their resources, and where could they recruit allies and rally reinforcement?

Any attempt at comparative analysis across so many divergent national histories is fraught with grave risks. It is easy to get lost in the wealth of fascinating detail, and it is equally easy to succumb to facile generalities and irresponsible abstractions. Scholarly prudence prompts us to proceed case by case, but intellectual impatience urges us to go beyond the analysis of concrete contrasts and try out alternative schemes of systematization across the known cases.

To clarify the logic of our approach to the comparative analysis of party systems, we have developed a model of alternative alliances and oppositions. We have posited several sets of actors, have set up a series of rules of alliance and opposition among these, and have tested the resultant typology of potential party systems against a range of empirically known cases.

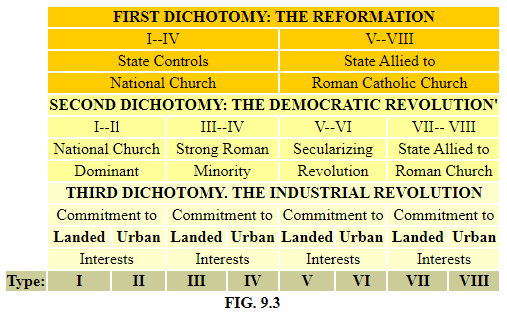

Our model seeks to reduce the bewildering variety of empirical party systems to a set of ordered consequences of decisions and developments at three crucial junctures in the history of each nation:

first, during the Reformation-the struggle for the control of the ecclesiastical organizations within the national territory;

second, in the wake of the Democratic Revolution after 1789-the conflict over the control of the vast machineries of mass education to be built up by the mobilizing nation-states;

finally, during the early phases of the Industrial Revolution -the opposition between landed interests and the claims of the rising commercial and industrial leadership in cities and towns.

Our eight types of alliance-opposition structure are in fact the simple combinatorial products of three successive dichotomies [see Fig. 9.3]. The model spells out the consequences of the fateful division of Europe brought about through Reformation and the Counter-Reformation. The outcomes of the early struggles between State and Church determined the structure of national politics in the era of democratization and mass mobilization three hundred years later. In Southern and Central Europe the Counter-Reformation had consolidated the position of the Church and tied its fate to the privileged bodies of the ancien régime. The result was a polarization of politics between a national-radical-secular movement and a Catholictraditionalists one. In North-West Europe, in Britain, and in Scandinavia, the settlement of the sixteenth century gave a very different structure to the cleavages of the nineteenth. The Established Churches did not stand in opposition to the nationbuilders in the way the Roman Catholic Church did on the Continent, and the Left movements opposed to the religious establishment found most of their support among newly enfranchised Dissenters, Nonconformists, and Fundamentalists in the peripheries and within the rising urban strata. In Southern and Central Europe the bourgeois opposition to the ancien régime tended to be indifferent if not hostile to the teachings of the Church: the cultural integration of the nation came first and the Church had to find whatever place it could within the new political order. In North-West Europe the opposition to the ancien régime was far from indifferent to religious values. The broad Left coalitions against the established powers recruited decisive support among orthodox Protestants in a variety of sectarian movements outside and inside the national churches.

The distinction between these two types of Left alliances against the inherited political structure is fundamental for an understanding of European political developments in the age of mass elections. It is of particular importance in the analysis of the religiously most divided of the European polities: types III and IV in our 2 X 2 X 2 schema. The religious frontiers of Europe went straight through the territories of the Low Countries, the old German Reich, and Switzerland; in each of these the clash between the nation-builders and the strong Roman Catholic minorities produced lasting divisions of the bodies politic and determined the structure of their party systems. The Dutch system came closest to a direct merger of the SouthernCentral type (VI-VIII) and the North-Western: on the one hand a nation-building party of increasingly secularized Liberals, on the other hand a Protestant Left recruited from orthodox milieus of the same type as those behind the old opposition parties in England and Scandinavia.

The difference between England and the Netherlands is indeed instructive. Both countries had their strong peripheral concentrations of Catholics opposed to central authority: the English in Ireland, the Dutch in the south. In Ireland, the cumulation of ethnic, social, and religious conflicts could not be resolved within the old system; the result was a history of intermittent violence and finally territorial separation. In the Netherlands the secession of the Belgians still left a sizeable Catholic minority, but the inherited tradition of corporate pluralism helped to ease them into the system. The Catholics established their own broad column of associations and a strong political party and gradually found acceptance within a markedly segmented but still cohesive national polity.

A comparison of the Dutch and the Swiss cases would add further depth to this analysis of the conditions for the differentiation of parties within national systems. Both countries come close to our type IV: Protestant national leadership, strong Catholic minorities, predominance of the cities in the national economy. In setting the assumption of our model we predicted a split in the peripheral opposition to the nationbuilders: one orthodox Protestant opposition and one Roman Catholic. This clearly fits the Dutch case but not so well the Swiss. How is this to be accounted for? Contrasts of this type open up fascinating possibilities of comparative historical analysis; all we can do here is to suggest a simple hypothesis. Our model not only simplifies complex historical developments through its strict selection of conditioning variables, it also reduces empirical continuities to crude dichotomies. The difference between the Dutch and the Swiss cases can possibly be accounted for through further differentiation in the centreperiphery axis. The drive for national centralization was stronger in the Netherlands and had been slowed down in Switzerland through the experiences of the war between the Protestant cantons and the Catholic Sonderbund. In the Netherlands the Liberal drive for centralization produced resistance both among the Protestants and the Catholics. In Switzerland the Radicals had few difficulties on the Protestant side and needed support in their opposition to the Catholics. The result was a party system of essentially the same structure as in the typical Southern-Central cases [types VI-VII].

In our model we have placed France with Italy as an example of an alliance-opposition system of type VI: Catholic dominance through the Counter-Reformation, secularization and religious conflict during the next phase of nation-building in the nineteenth century, clear predominance of the cities in national politics. But this is an analytical juxtaposition of polities with diametrically opposed histories of development and consolidation-France one of the oldest and most centralized nationstates in Europe, Italy a territory unified long after the French revolutions had paved the way for the participant nation, the integrated political structure committing the entire territorial population to the same historical destiny. To us this is not a weakness in our model, however. The party systems of the countries are curiously similar, and any scheme of comparative analysis must somehow or other bring this out. The point is that our distinction between nation-builder alliances and periphery alliances must take on very different meanings in the two contexts. In France the distinction between centre and periphery was far more than a matter of geography; it reflected long-standing historical commitments for or against the Revolution. As spelt out in detail in Siegfrieds classic Tableau, the Droite had its strongholds in the districts which had most stubbornly resisted the revolutionary drive for centralization and equalization, but it was far more than a movement of peripheral protest-it was a broad alliance of alienated élite groups, of frustrated nation-builders who felt that their rightful powers had been usurped by men without faith and without roots. In Italy there was no basis for such a broad alliance against the secular nation-builders, since the established local élites offered little resistance to the lures of trasformismo, and the Church kept its faithful followers out of national politics for nearly two generations.

These contrasts during the initial phases of mass mobilization had far-reaching consequences for each party system. With the broadening of the electorates and the strengthening of the working-class parties, the Church felt impelled to defend its position through its own resources. In France, the result was an attempt to divorce the defence of the Catholic schools from the defence of the established rural hierarchy. This trend had first found expression through the establishment of Christian trade unions and in 1944 finally led to the formation of the MRP. The burden of historic commitments was too strong, however; the young party was unable to establish itself as a broad mass party defending the principles of Christian democracy. By contrast, in Italy, history had left the Church with only insignificant rivals to the right of the working-class parties. The result was the formation of a broad alliance of a variety of interests and movements, frequently at loggerheads with each other, but united in their defence of the rights of the central institution of the fragmented ancien régime, the Roman Catholic Church. In both cases there was a clear-cut tendency towards religious polarization, but differences in the histories of nation-building made for differences in the resultant systems of party alliances and oppositions.

We could go into further detail in every one of the eight types distinguished in our model, but this would take us too far into single-country histories. We are less concerned with the specifics of the degrees of fit in each national case than with the overall structure of the model. There is clearly nothing final about any such scheme; it simply sets a series of themes for detailed comparisons and suggests ways of organizing the results within a manageable conceptual framework. The model is a tool and its utility can be tested only through continuous development: through the addition of further variables to account for observed differences as well as through refinements in the definition and grading of the variables already included.

The Fourth Step: Variations in the Strength and Structure of the Working-Class Movements

Our three-step model stops short at a point before the decisive thrust towards universal suffrage. It pinpoints sources of variations in the systems of division within the independent strata of the European national electorates, among the owners of property and the holders of professional or educational privileges qualifying them for the vote during the régime censitaire.

But this is hardly more than half the story. The extension of the suffrage to the lower classes changed the character of each national political system, generated new cleavages, and brought about a restructuring of the old alignments.

Why did we not bring these important developments into our model of European party systems? Clearly not because the three first cleavage lines were more important than the fourth in the explanation of any one national party system. On the contrary, in sheer statistical terms the fourth cleavage lines will in at least half of the cases under consideration explain much more of the variance in the distributions of full-suffrage votes than any one of the others. We focused on the three first cleavage lines because these were the ones that appear to account for most of the variance among systems: the interactions of the centreperiphery, State-Church, and land-industry cleavages tended to produce much more marked, and apparently much more stubborn, differences among the national party systems than any of the cleavages brought about through the rise of the working-class movements.

We could of course have gone on to present a four-step model immediately (in fact, we did in an earlier draft), but this proved very cumbersome and produced a variety of uncomfortable redundancies. Clearly what had to be explained was not the emergence of a distinctive working-class movement at some point or other before or after the extension of the suffrage but the strength and solidarity of any such movement, its capacity to mobilize the underprivileged classes for action and its ability to maintain unity in the face of the many forces making for division and fragmentation. All the European polities developed some sort of working-class movement at some point between the first extensions of the suffrage and the various post-democratic attempts at the repression of partisan pluralism. To predict the presence of such movements was simple; to predict which ones would be strong and which ones weak, which ones unified and which ones split down the middle, required much more knowledge of national conditions and developments and a much more elaborate model of the historical interaction process. Our three-step model does not go this far for any party; it predicts the presence of such-and-such parties in polities characterized by such-and-such cleavages, but it does not give any formula for accounting for the strength or the cohesion of any one party. This could be built into the model through the introduction of various population parameters (per cent speaking each language or dialect, per cent committed to each of the churches or dissenting bodies, ratios of concentrations of wealth and dependent labour in industry versus landed estates), and possibly of some indicators of the cleavage distance (differences in the chances of interaction across the cleavage line, whether physically determined or normatively regulated), but any attempt in this direction would take us much too far in this all-too-long introductory essay. At this point we limit ourselves to an elementary discussion of the between-system variations which would have to be explained through such an extension of our model. We shall suggest a fourth step and point to a possible scheme for the explanation of differences in the formation of national party systems under the impact of universal suffrage.

Our initial scheme of analysis posited four decisive dimensions of cleavage in Western polities. Our model for the generation of party systems pin-pointed three crucial junctures in national history corresponding to the first three of these dimensions [see Fig. 9.4]. It is tempting to add to this a fourth dimension and a fourth juncture:

There is an intriguing cyclical movement in this scheme. The process gets under way with the breakdown of one supranational order and the establishment of strong territorial bureaucracies legitimizing themselves through the standardizing of nationally distinct religions and languages, and it ends with a conflict over national versus international loyalties within the last of the strata to be formally integrated into the nation-state, the rural and the industrial workers.

The conditions for the development of distinctive workingclass parties varied markedly from country to country within Europe. These differences emerged well before World War I. The Russian Revolution did not generate new cleavages but simply accentuated long-established lines of division within the working-class élite.

Our three-step model does not produce clear-cut predictions of these developments. True enough, the most unified and the most domesticable working-class movements emerged in the Protestant-dominated countries with the smoothest histories of nation-building: Britain, Denmark, and Sweden (types I and II in our model). Equally true, the Catholic-dominated countries with difficult or very recent histories of nation-building also produced deeply divided, largely alienated working-class movements-France, Italy, Spain (types V and VI). But other variables clearly have to be brought into account for variations in the intermediary zone between the Protestant North-West and the Latin South (types III and IV, VII and VIII). Both the Austrian and the German working-class movements developed their distinctive counter-cultures against the dominant national élites. The Austrian Socialist Lager, heavily concentrated as it was in Vienna, was able to maintain its unity in the face of the clerical-conservatives and the pan-German nationalists after the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire. By contrast, the German working-class movement was deeply divided after the defeat in 1918. Sharply contrasted conceptions of the rules of the political game stood opposed to each other and were to prove fatal in the fight against the wave of mass nationalism of the early thirties. In Switzerland and the Netherlands (both type IV in our scheme), the Russian and the German revolutions produced a few disturbances, but the leftward split-offs from the main working class by parties were of little significance. The marked cultural and religious cleavages reduced the potentials for the Socialist parties, but the traditions of pluralism were gradually to help their entry into national politics.

Of all the intermediary countries Belgium (type VIII in our model) presents perhaps the most interesting case. By our overall rule, the Belgian working class should be deeply divided: a thoroughly Catholic country with a particularly difficult history of nation-building across two distinct language communities. In this case the smallness and the international dependence of the nation may well have created restraints on the internal forces of division and fragmentation. Val Lorwin has pointed to such factors in his analysis of Belgian French contrasts:

The reconciliation of the Belgian working class to the political and social order, divided though the workers are by language and religion and the Flemish-Walloon question, makes a vivid contrast with the experience of France. The differences did not arise from the material fruits of economic growth, for both long were rather low-wage countries, and Belgian wages were the lower. In some ways the two countries had similar economic development. But Belgiums industrialization began earlier; it was more dependent on international commerce, both for markets and for its transit trade; it had a faster growing population; and it became much more urbanized than France. The small new nation, the cockpit of Europe, could not permit itself social and political conflict to the breaking point. Perhaps France could not either, but it was harder for the bigger nation to realize it. 18

The contrast between France, Italy, and Spain on the one hand and Austria and Belgium on the other suggests a possible generalization: the working-class movement tended to be much more divided in the countries where the nation-builders and the Church were openly or latently opposed to each other during the crucial phases of educational development and mass mobilization (types V and VI) than in the countries where the Church had, at least initially, sided with the nation-builders against some common enemy outside (an alliance against Protestant Prussia and the dependent Habsburg peoples in the case of Austria; against the Calvinist Dutch in the case of Belgium). This fits the Irish case as well. The Catholic Church was no less hostile to the English than the secular nationalists, and the union of the two forces not only reduced the possibilities of a polarization of Irish politics on class lines but made the likelihood of a Communist splinter of any importance very small indeed.

It is tempting to apply a similar generalization to the Protestant North: the greater the internal division during the struggle for nationhood, the greater the impact of the Russian Revolution on the divisions within the working class. We have already pointed to the profound split within the German working class. The German Reich was a late-comer among European nations, and none of the territorial and religious conflicts within the nation was anywhere near settlement by the time the working-class parties entered the political arena. Among the northern countries the two oldest nations, Denmark and Sweden, were least affected by the Communist-Socialist division. The three countries emerging from colonial status were much more directly affected: Norway (domestically independent from 1814, a sovereign state from 1905) for only a brief period in the early 1920s; Finland (independent in 1917) and Iceland (domestically independent in 1916 and a sovereign state from 1944) for a much longer period. These differences among the northern countries have been frequently commented on in the literature of comparative politics. The radicalization of the Norwegian Labour party has been interpreted within several alternative models, one emphasizing the alliance options of the party leaders, another the grass-roots reactions to sudden industrialization in the peripheral countryside, and a third the openness of the party structure and the possibilities of quick feedback from the mobilized voters. There is no doubt that the early mobilization of the peasantry and the quick victory over the old regime of the officials had left the emerging Norwegian working-class party much more isolated, much less important as a coalition partner, than its Danish and Swedish counterparts. There is also a great deal of evidence to support the old [Eduard] Bull hypothesis of the radicalizing effects of sudden industrialization, but recent research suggests that this was only one element in a broad process of political change. The Labour party recruited many more of its voters in the established cities and in the forestry and the fisheries districts, but the openness of the party structure allowed the radicals to establish themselves very quickly and to take over the majority wing of the party during the crucial years just after the Russian Revolution. This very openness to rank-and-file influences made the alliance with Moscow very short-lived; the Communists split off in 1924 and the old majority party joined the nation step by step until it took power in 1935.

Only two of the Scandinavian countries retained strong Communist parties after World War II-Finland and Iceland. Superficially these countries have two features in common: prolonged struggles for cultural and political independence, and late industrialization. In fact the two countries went through very different processes of political change from the initial phase of nationalist mobilization to the final formation of the full-suffrage party system. One obvious source of variation was the distance from Russia. The sudden upsurge of the Socialist party in Finland in 1906 (the party gained 37 per cent of the votes cast at the first election under universal suffrage) was part of a general wave of mobilization against the Tsarist regime. The Russian Revolution of 1917 split Finland down the middle; the working-class voters were torn between their loyalty to their national culture and its social hierarchy and their solidarity with their class and its revolutionary defenders. The victory of the Whites and the subsequent suppression of the Communist party (1919-21, 1923-5, 1930-44) left deep scars; the upsurge of the leftist SKDL after the Soviet victory in 1945 reflected deep-seated resentments not only against the lords and the employers of labour but generally against the upholders of the central national culture. The split in the Icelandic labour movement was much less dramatic; in the oldest and smallest of the European democracies there was little basis for mass conflicts, and the oppositions between Communist sympathizers and Socialists appeared to reflect essentially personal antagonisms among groups of activists.

IMPLICATIONS FOR COMPARATIVE POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY

We have pushed our attempt at a systematization of the comparative history of partisan oppositions in European polities up to some point in the 1920s, to the freezing of the major party alternatives in the wake of the extension of the suffrage and the mobilization of major sections of the new reservoirs of potential supporters. Why stop there? Why not pursue this exercise in comparative cleavage analysis right up to the 1960s? The reason is deceptively simple: the party systems of the 1960s reflect, with few but significant exceptions, the cleavage structures of the 1920s. This is a crucial characteristic of Western competitive politics in the age of high mass consumption: the party alternatives, and in remarkably many cases the party organizations, are older than the majorities of the national electorates. To most of the citizens of the West. the currently active parties have been part of the political landscape since their childhood or at least since they were first faced with the choice between alternative packages on election day.

This continuity is often taken as a matter of course; in fact it poses an intriguing set of problems for comparative sociological research. An amazing number of the parties which had established themselves by the end of World War I survived not only the onslaughts of Fascism and National Socialism but also another world war and a series of profound changes in the social and cultural structure of the polities they were part of. How was this possible? How were these parties able to survive so many changes in the political, social, and economic conditions of their operation? How could they keep such large bodies of citizens identifying with them over such long periods of time, and how could they renew their core clienteles from generation to generation?

There is no straightforward answer to any of these questions. We know much less about the internal management and the organizational functioning of political parties than we do about their socio-cultural base and their external history of participation in public decision-making.

To get closer to an answer we would clearly have to start out from a comparative analysis of the old and the new parties: the early mass parties formed during the final phase of suffrage extension, and the later attempts to launch new parties during the first decades of universal suffrage. It is difficult to see any significant exceptions to the rule that the parties which were able to establish mass organizations and entrench themselves in the local government structures before the final drive towards maximal mobilization have proved the most viable. The narrowing of the support market brought about through the growth of mass parties during this final thrust towards fullsuffrage democracy clearly left very few openings for new movements. Where the challenge of the emerging workingclass parties had been met by concerted efforts of countermobilization through nationwide mass organizations on the liberal and the conservative fronts, the leeway for new party formations was particularly small; this was the case whether the threshold of representation was low, as in Scandinavia, or quite high, as in Britain. Correspondingly the post-democratic party systems proved markedly more fragile and open to newcomers in the countries where the privileged strata had relied on their local power resources rather than on nationwide mass organizations in their efforts of mobilization.

France was one of the first countries to bring a maximal electorate into the political arena, but the mobilization efforts of the established strata tended to be local and personal. A mass organization corresponding to the Conservative party in Britain was never developed. There was very little narrowing of the support market to the right of the PCF and the SFIO and consequently a great deal of leeway for innovation in the party system even in the later phases of democratization.

There was a similar asymmetry in Germany: strong mass organizations on the left but marked fragmentation on the right. The contrast between Germany and Britain has been rubbed in at several points in our analysis of cleavage structures. The contrast with Austria is equally revealing; there the three-Lager constellation established itself very early in the mobilization process, and the party system changed astoundingly little from the Empire to the First Republic, and from the First to the Second. The consolidation of conservative support around the mass organizations of the Catholic Church clearly soaked up a great deal of the mobilization potential for new parties. In Wilhelmine and Weimar Germany the only genuine mass organization to the right of the Social Democrats was the Catholic Zentrum; this still left a great deal of leeway for post-democratic party formations on the Protestant right. Ironically, it was the defeat of the National Socialist regime and the loss of the Protestant East which opened up an opportunity for some stabilization of the German party system. With the establishment of the regionally divided CDU/CSU the Germans were for the first time able to approximate a broad conservative party of the British type. It was not able to establish as solid a membership organization but proved, at least until the debacle of 1966, amazingly effective in aggregating interests across a wide range of strata and sectors of the federal community.

Two other countries of the West have experienced spectacular changes in their party systems since the introduction of universal suffrage and deserve some comment in this context -Italy and Spain. The Italian case comes close to the German: both went through a painful process of belated unification; both were deeply divided within their privileged strata between nation-builders (Prussians, Piedmontese) and Catholics; both had been slow to recognize the rights of the working-class organizations. The essential difference lay in the timing of the party developments. In the Reich a differentiated party struc-. ture had been allowed to develop during the initial mobilization phase and had been given another fifteen years of functioning during the Weimar Republic. In Italy, by contrast, the StateChurch split was so profound that a structurally responsive party system did not see the light before 1919-three years before the March on Rome. There had simply been no time for the freezing of any party system before the post-democratic revolution, and there was very little in the way of a traditional party system to fall back on after the defeat of the Fascist regime in 1944. True, the Socialists and the Popolari had had their brief spell of experience of electoral mobilization, and this certainly counted when the PCI and the DC established themselves in the wake of the war. But the other political forces had never been organized for concerted electoral politics and left a great deal of leeway for irregularities in the mobilization market. The Spanish case has a great deal in common with the French: early unification but deep resentments against central power in some of the provinces and early universalization of the suffrage but weak and divided party organizations. The Spanish system of sham parliamentarianism and caciquismo had not produced electoral mass parties of any importance by the time the double threat of secessionist mobilization and working-class militancy triggered off nationalist counter-revolutions, first under Primo de Rivera in 1923, then with the Civil War in 1936.

These four spectacular cases of disruptions in the development of national party systems do not in themselves invalidate our initial formulation. The most important of the party alternatives got set for each national citizenry during the phases of mobilization just before or just after the final extension of the suffrage and have remained roughly the same through decades of subsequent changes in the structural conditions of partisan choice. Even in the three cases of France, Germany, and Italy the continuities in the alternatives are as striking as the disruptions in their organizational expressions. On this score the French case is in many ways the most intriguing. There was no period of internally generated disruption of electoral politics (the Petain-Laval phase would clearly not have occurred if the Germans had not won in 1940), but there have been a number of violent oscillations between plebiscitarian and representative models of democracy and marked organizational fragmentation both at the level of interest articulation and at the level of parties. In spite of these frequent upheavals no analyst of French politics is in much doubt about the underlying continuities of sentiment and identification on the right no less than on the left of the political spectrum. The voter does not just react to immediate issues but is caught in an historically given constellation of diffuse options for the system as a whole.

'Political Science' 카테고리의 다른 글

| The Two-Dimensional Conceptual Map of Democracy (0) | 2022.12.09 |

|---|---|

| Electoral Institutions, Cleavage Structures, and the Number of Parties (0) | 2022.12.05 |

| 9. CLEAVAGE STRUCTURES, PARTY SYSTEMS, AND VOTER ALIGNMENTS (1 of 2) (0) | 2022.11.25 |

| 3. Evaluating Electoral Systems (0) | 2022.11.22 |

| 2. Classifying Electoral Systems (0) | 2022.11.20 |